by Rachel Robison-Greene

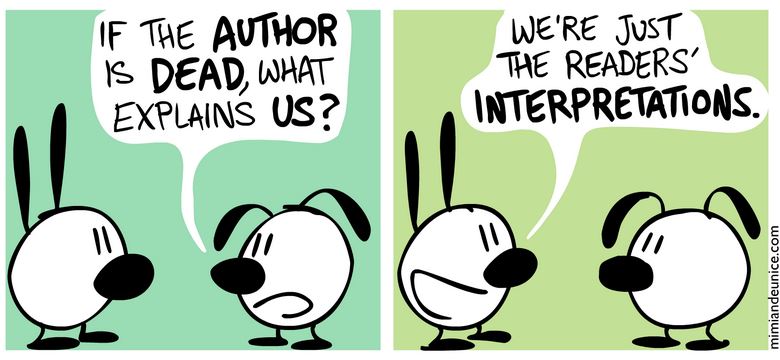

The Trolley Problem, once a thought experiment students encountered for the first time in an Introduction to Philosophy classroom, has become a well-known cultural meme. It is depicted in various iterations in cartoons across the internet. The standard story involves a person choosing to pull a lever so that a trolley runs over one person tied to the tracks rather than five. People have imagined all sorts of identities for the individuals involved, up to and including a billionaire at the lever choosing to direct the trolley to run over many people in order to protect bags of money. All of these scenarios share a key feature in common—they encourage those contemplating them to consider the consequences that might result from the decision the lever-puller makes.

Much emerging technology encourages people to reason along similar lines. Consider the case of autonomous vehicles. Critics and ethically inclined collaborators have been quick to point out that these vehicles will not be naturally inclined to make decisions guided by moral considerations. If we want these vehicles to make defensible moral decisions in tricky circumstances, we’ll need to program them to do so. Discussion of these issues often proceeds along broadly consequentialist lines: identify things that are valuable and maximize them and identify things that have disvalue and minimize them. If we think that the life of a human is more valuable than, say, the life of an ill-fated duck crossing the street, then the life of the human should be prioritized when there is a choice between them. If we value saving a greater number of lives rather than a lesser number, then perhaps we should program autonomous vehicles to sacrifice the driver when the choice is between the death of the driver and the deaths of a greater number of people. In any case, the decision-making metric involves weighing consequences. The same is true with algorithmic decision making made by other forms of AI. This includes AI used in our most important institutions: education, health care, the criminal justice system, and the military. Read more »

Like many other video gamers (nearly eight million, in fact), I have spent no small portion of recent weeks in the robot-infested, post-diluvian wastes of late-22nd-Century Italy, looting remnants of a collapsed civilization while hoping that a fellow gamer won’t sneak up and murder me for the scraps in my pockets. This has been much more fun than the preceding description might lead you to believe, if you are not a fan of such grim fantasy playgrounds. It has also, interestingly, afforded rather heart-warming displays of the better side of human nature, despite the occasional predatory ambush or perfidious betrayal. It helps somewhat that nobody really dies in this game; they just get “downed” and then “knocked out” if not revived in time, leaving behind whatever gear they were carrying (except for what they were able to hide in their “safe pocket”, the technical and anatomical details of which are left to the player’s imagination).

Like many other video gamers (nearly eight million, in fact), I have spent no small portion of recent weeks in the robot-infested, post-diluvian wastes of late-22nd-Century Italy, looting remnants of a collapsed civilization while hoping that a fellow gamer won’t sneak up and murder me for the scraps in my pockets. This has been much more fun than the preceding description might lead you to believe, if you are not a fan of such grim fantasy playgrounds. It has also, interestingly, afforded rather heart-warming displays of the better side of human nature, despite the occasional predatory ambush or perfidious betrayal. It helps somewhat that nobody really dies in this game; they just get “downed” and then “knocked out” if not revived in time, leaving behind whatever gear they were carrying (except for what they were able to hide in their “safe pocket”, the technical and anatomical details of which are left to the player’s imagination). Chiharu Shiota. Infinite Memory, 2025.

Chiharu Shiota. Infinite Memory, 2025. S. Abbas Raza: You may have heard of

S. Abbas Raza: You may have heard of

Preparing a worksheet with negative-number calculations where all the digits are sixes and sevens. Telling myself it’s meant to take the fun out of it for them – like a sex ed teacher having their students say ‘penis’ one hundred times before starting the unit. Definitely not the whole story, but plausible: as a middle school math teacher I am more than justified in trying to tame the phenomenon. In fact, I have drawn a firm line; just seeing a 6 anywhere in an exercise is decidedly not an appropriate reason for doing the meme. Really, we need to get on with the lesson now; I will count to five.

Preparing a worksheet with negative-number calculations where all the digits are sixes and sevens. Telling myself it’s meant to take the fun out of it for them – like a sex ed teacher having their students say ‘penis’ one hundred times before starting the unit. Definitely not the whole story, but plausible: as a middle school math teacher I am more than justified in trying to tame the phenomenon. In fact, I have drawn a firm line; just seeing a 6 anywhere in an exercise is decidedly not an appropriate reason for doing the meme. Really, we need to get on with the lesson now; I will count to five. Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony helps explain how the power structure of modern liberal-democratic societies maintains authority without relying on overt force. Many definitions of hegemony point out that it creates “common sense,” the assumptions a society accepts as natural and right.

Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony helps explain how the power structure of modern liberal-democratic societies maintains authority without relying on overt force. Many definitions of hegemony point out that it creates “common sense,” the assumptions a society accepts as natural and right.

Art is dangerous. It’s time people remembered that and recognized the fullness of it. For if art is to remain important or even relevant in the current moment, then it’s long past time artists stopped flashing dull claws and pretending they had what it takes to slice through ignorance. We need them swallow their feel-good clichés and to begin sharpening their blades. We need dangerous art, and we cannot afford much more art that its creators believe is dangerous when it is not.

Art is dangerous. It’s time people remembered that and recognized the fullness of it. For if art is to remain important or even relevant in the current moment, then it’s long past time artists stopped flashing dull claws and pretending they had what it takes to slice through ignorance. We need them swallow their feel-good clichés and to begin sharpening their blades. We need dangerous art, and we cannot afford much more art that its creators believe is dangerous when it is not. Emma Wilkins’ excellent piece “

Emma Wilkins’ excellent piece “