by Derek Neal

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea:

The writer is the enemy in Robert Altman’s 1992 film, The Player. The person movie studios can’t do without, because they need scripts to make movies, but whom they also can’t stand, because writers are insufferable and insist upon unreasonable things, like being paid for their work and not having their stories changed beyond recognition. Griffin Mill, a movie executive played by Tim Robbins, is known as “the writer’s executive,” but a new executive, named Larry Levy and played by Peter Gallagher, threatens to usurp Mill partly by suggesting that writers are unnecessary. In a meeting introducing Levy to the studio’s team, he explains his idea:

I’ve yet to meet a writer who could change water into wine, and we have a tendency to treat them like that…A million, a million and a half for these scripts. It’s nuts. And I think avoidable…All I’m saying is I think there’s a lot of time and money to be saved if we came up with these stories on our own.

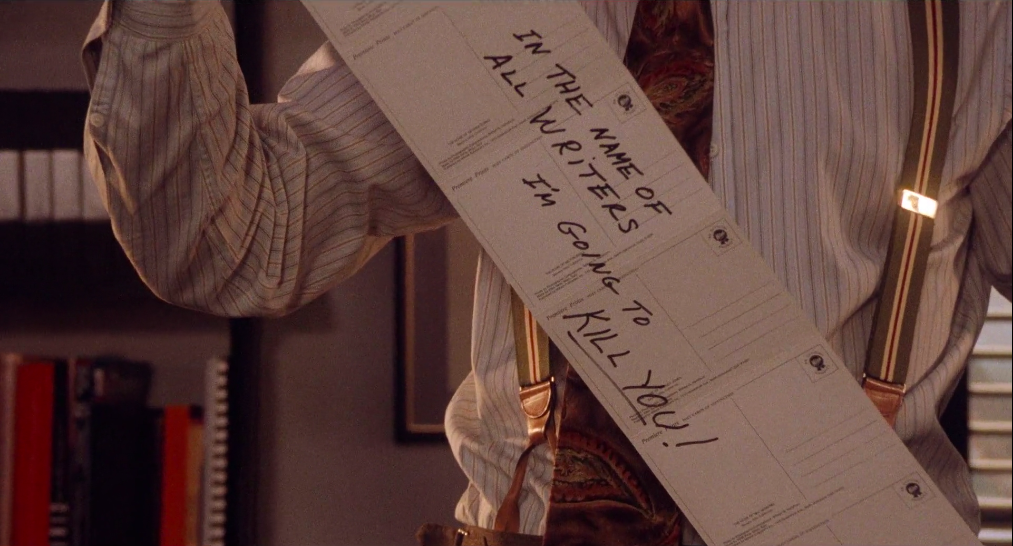

Writers are slow and they cost money. They get writer’s block. They miss deadlines. They are an impediment to efficiency and progress, and if they are ignored, they might get angry, as Mill finds out when he starts receiving threatening postcards from an anonymous scriptwriter that say things like, “I TOLD YOU MY IDEA AND YOU SAID YOU’D GET BACK TO ME. WELL?” and “YOU ARE THE WRITERS ENEMY! I HATE YOU.”

Writers may be Mill’s “long suit,” as a lawyer at a party tells him, but as Mill himself notes, he hears thousands of pitches a year, and he can only pick twelve. The perennial losers are bound to become resentful, disillusioned—even dangerous. After receiving one particularly disturbing postcard (IN THE NAME OF ALL WRITERS IM GOING TO KILL YOU!), Mill decides to go through his call logs to discover who could be sending him such messages. He thinks it must be a man named David Kahane, and after learning that he’s at a cinema in Pasadena, Mill drives out to meet him, hoping to placate him with a scriptwriting offer for a film that will likely never be made. Read more »

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. April, 2025.

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. April, 2025. Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

Morality, according to this view, is more like taste, and in matters of taste I don’t expect others to be like me. This is of course incoherent since the very imperative to be non-judgmental is itself a moral demand, which must claim some level of objectivity since it is a rule that others are expected to follow. Judging others, according to non-judgmentalism, is something we ought not to do. It is presented as an objective moral rule.

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.

On a hot summer evening in Baltimore last year, the daylight still washing over the city, I sat on my front porch, drinking a beer with a friend. Not many people passed by. Most who did were either walking a dog or making their way to the corner tavern. And then an increasingly rare sight in modern America unfolded. Two boys, perhaps ages 8 and 10, cruised past us on a bike they were sharing. The older boy stood and pedaled while the younger sat behind him.