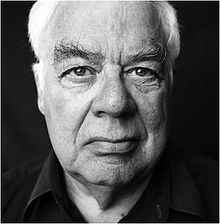

by Dave Maier

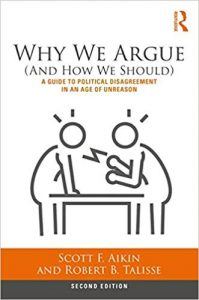

If someone accuses you of “ethnocentrism,” they’re probably saying that you come off as arrogant or dogmatic in rejecting other cultures’ practices as illegitimate or inferior. Richard Rorty, however, applies that term to himself, and indeed takes it to be a central part of his own view. Since he’s not, I take it, thereby confessing to arrogance or dogmatism, he must be using the term idiosyncratically. Even so, Rorty’s conception has drawn criticism not only from the usual suspects but also from perhaps the most prominent critic of “ethnocentrism” in its usual sense: anthropologist Clifford Geertz, a thinker with whom, given their shared liberalism (generally speaking), as well as their shared intellectual inheritance from Wittgenstein, we might expect Rorty to agree.

So what’s going on here? As noted, Rorty’s ethnocentrism (I’m going to stop putting the word in quotes now) plays a central role in his philosophy. In particular, he tells us, it’s the conceptual link between his “antirepresentationalist” view of inquiry, on the one hand, and his (somewhat self-mockingly dubbed) “postmodern bourgeois liberalism” on the other:

“[A]n antirepresentationalist view of inquiry leaves one without a skyhook with which to escape from the ethnocentrism produced by acculturation, but […] the liberal culture of recent times has found a strategy for avoiding the disadvantage of ethnocentrism. This is to be open to encounters with other actual and possible cultures, and to make this openness central to its self-image. This culture is an ethnos which prides itself on its suspicion of ethnocentrism – on its ability to increase the freedom and openness of encounters, rather than on its possession of truth.” (Objectivity, Relativism, and Truth, p. 2)

That Rorty’s ethnocentrism isn’t just some free-floating doctrine (which shouldn’t be surprising, given his lack of interest in coming up with philosophical theories which (simply) “get reality right”) means two things. First, we’ll need to see what it’s doing in order to see what it is. Second, we won’t be able to dislodge it and replace it with something better unless our suggested replacement isn’t simply a better explanation of, say, belief and inquiry, but also fits just as well with the rest of what we say as Rorty’s ethnocentrism does with the rest of his thought. This may require giving up some of those other things as well – for better or worse. (Was anyone actually happy with “postmodern bourgeois liberalism”?) Read more »

Opera as resistance? Music as re-enchantment?

Opera as resistance? Music as re-enchantment?

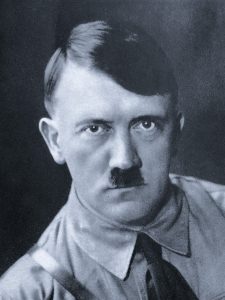

When it comes to evil, nobody beats Hitler. He committed the biggest mass murder of innocent humans in all of history.

When it comes to evil, nobody beats Hitler. He committed the biggest mass murder of innocent humans in all of history.

Many years ago in 1991, in my first job out of college, I worked for a small investment bank. By 1994, I was working in its IT department. One of my tasks was PC support and I had a modem attached to my computer so that I could connect to Compuserve for research on technical issues. Yes, this was the heydey of Compuserve, the year that the first web browser came out and a time when most people had very little idea, if any, what this Internet thing was.

Many years ago in 1991, in my first job out of college, I worked for a small investment bank. By 1994, I was working in its IT department. One of my tasks was PC support and I had a modem attached to my computer so that I could connect to Compuserve for research on technical issues. Yes, this was the heydey of Compuserve, the year that the first web browser came out and a time when most people had very little idea, if any, what this Internet thing was.

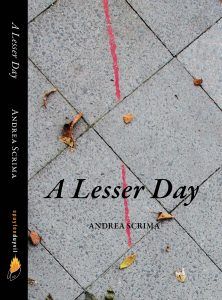

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.

Novels set in New York and Berlin of the 1980s and 1990s, in other words, just as subculture was at its apogee and the first major gentrification waves in various neighborhoods of the two cities were underway—particularly when they also try to tell the coming-of-age story of a young art student maturing into an artist—these novels run the risk of digressing into art scene cameos and excursions on drug excess. In her novel A Lesser Day (Spuyten Duyvil, second edition 2018), Andrea Scrima purposely avoids effects of this kind. Instead, she concentrates on quietly capturing moments that illuminate her narrator’s ties to the locations she’s lived in and the lives she’s lived there.

Little Miracles 2:

Little Miracles 2:

The dangers of climate change pose a threat to all of humankind and to ecosystems all over the world. Does this mean that all humans need to equally shoulder the responsibility to mitigate climate change and its effects? The concept of CBDR (common but differentiated responsibilities) is routinely discussed at international negotiations about climate change mitigation. The basic principle of CBDR in the context of climate change is that highly developed countries have historically contributed far more than to climate change and therefore need to reduce their carbon footprint far more than less developed countries. The per capita rate of vehicles in the United States is approximately 90 cars per 100 people, whereas the rate in India is 5 cars per 100 people. The total per capita carbon footprint includes a plethora of factors such as carbon emissions derived from industry, air travel and electricity consumption of individual households. As of 2015, the

The dangers of climate change pose a threat to all of humankind and to ecosystems all over the world. Does this mean that all humans need to equally shoulder the responsibility to mitigate climate change and its effects? The concept of CBDR (common but differentiated responsibilities) is routinely discussed at international negotiations about climate change mitigation. The basic principle of CBDR in the context of climate change is that highly developed countries have historically contributed far more than to climate change and therefore need to reduce their carbon footprint far more than less developed countries. The per capita rate of vehicles in the United States is approximately 90 cars per 100 people, whereas the rate in India is 5 cars per 100 people. The total per capita carbon footprint includes a plethora of factors such as carbon emissions derived from industry, air travel and electricity consumption of individual households. As of 2015, the