by Leanne Ogasawara

“Someday, I’d like to visit Salzburg when the Summer Festival’s not going on. That way, I can see if the place is real; for I just can’t help wondering if Salzburg is not some kind of enchanted fairy world, which only comes into being when the music is playing…”

“Nonsense” said our guide matter-of-factly.“In Salzburg, the music never stops playing!” She paused and then added more circumspectly: “But of course, the Summer Festival is the pièce de résistance. And we Salzburgers wait for it all year long.”

Salzburgers are not the only ones who look forward to the festival all year long; for year after year—like some gigantic magnet—it draws artists and music lovers from all over the world. To call it larger than life would only be an understatement; for the festival exists outside of regular time; beyond ordinary life. Super-charged and surprisingly playful, artists, who don’t often work together, perform works that are cutting-edge and often quite risky, because –well, it’s the festival! And if you aren’t taking chances then you run the risk of being Disneylandified, a previous festival director once said. Along with the artists, music lovers also arrive to this city like pilgrims. For unlike during the regular season, when music is more of a diversion from our everyday lives, during festival season attendees are able to immerse themselves completely into an enchanted world that begins and ends with art.

Opera as resistance? Music as re-enchantment?

Opera as resistance? Music as re-enchantment?

If you don’t like the “high brow” arts –or disapprove of the opera (you know who you are)—beware! Because Salzburg is the belly of the beast! We upped our game by booking a room at the Hotel Goldener Hirsch. I had read in an opera magazine that this was “the place” to stay for opera goers. I hadn’t, however, really thought things through; as we were not quite prepared for the jet-set atmosphere of the place –not to mention being severely under-dressed! Our own inadequacies aside, again and again during those four days I kept thinking about the Japanese expression ichi-go ichi-e (一期一会).

Have you heard of that term from Zen Buddhism? It basically means something like “One time, one encounter.”

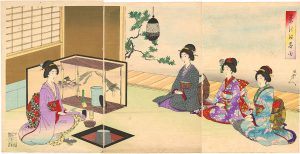

In my thirties, I studied tea ceremony in Japan. Attending lessons for many years, I can with great embarrassment tell you that I never did learn to make a bowl of tea properly. It is very complicated: every time I felt myself –at last– to be on the cusp of memorizing the ritualized procedures, the season would change. I had to put aside all that I had learned to absorb the new rituals of the new season… So many seasons, so many ways of making tea! But the one thing that I managed to learn by heart was this concept of “One time, one encounter.”

Life is, after all, constantly shuffling the deck, and each and every tea gathering was precious and unique; a once in a life time combination of people, utensils and experiences. Never again would the same exact group come together to drink tea in a room with just that particular combination of hanging scroll, blend of tea, fragrance of incense; with that particular arrangement of flowers (appearing in the vessel as if growing in a field…)– the tea bowl and the brazier; the colors of my friends’ kimono and the quality of our laughter that day–it was all a unique moment. A heightened moment. A perfect unfolding of “now.”

Life is, after all, constantly shuffling the deck, and each and every tea gathering was precious and unique; a once in a life time combination of people, utensils and experiences. Never again would the same exact group come together to drink tea in a room with just that particular combination of hanging scroll, blend of tea, fragrance of incense; with that particular arrangement of flowers (appearing in the vessel as if growing in a field…)– the tea bowl and the brazier; the colors of my friends’ kimono and the quality of our laughter that day–it was all a unique moment. A heightened moment. A perfect unfolding of “now.”

When I first began lessons, my teacher wondered how the others would take to an American friend in the tearoom. This was in the conservative countryside of Japan. Instead of having us tell each other our life’s resumes, before even giving them my name, she opened up a huge book of textiles that looked to be a hundred years old and asked us to tell each other what we liked. And so we gathered around the heavy book (they in their mothers’ kimonos and me in a skirt) and talked about the particular shades of blue that appealed to us or about how these textiles had arrived in Japan (By way of China? Or was this one from Kansai? I loved the sarasa from India, as did Nobuko, the woman I became closest with). Every week, those lessons were not just highlighted in my mind, but it truly felt as if every moment in the tearoom was larger than the rest of my life. More poignant, more memorable, more treasured –even now. And every so often the scroll hanging in the alcove would be a piece of calligraphy written vertically, ichi-go ichi-e (一期一会).

The miracle of that stretched out and inflated moment–outside time; outside daily life came back to me vividly in Salzburg, as I thought about how alive I felt.

The miracle of that stretched out and inflated moment–outside time; outside daily life came back to me vividly in Salzburg, as I thought about how alive I felt.

There is a famous poem by Yosano Akiko:

清水へ祇園をよぎる桜月夜こよひ逢ふひとみなうつくしき (みだれ髪/与謝野晶子)

There is the woman walking in Kyoto. She is going to go cherry blossom viewing by moonlight in Kiyomizu. Her heart so full from this perfect moment, she declares that all the people she sees walking in the Gion are beautiful.

I have always loved that poem. And, it was true, everyone did look so beautiful that first night in Salzburg, as we all walked slowly out of the hall and made our way back toward the Goldener Hirsch along the long stretch of festival hall, lined with flags with the mountains pressing close. Dressed and bejeweled like movie stars and lit up with light as they spoke excitedly about the music, I felt like I was in a dream. Real life seemed a million miles away.

And so, I was not surprised to read that the possibility for opening up alternative ways of being was one of the stated objectives of the Salzburg Music Festival when it was first conceived in the early years of the 20th century. Founding fathers of the festival–the Holy Trinity of stage director Max Reinhardt, writer Hugo von Hofmannthal, and composer Richard Strauss– purposively set out to create a festival that would exist far away from the relentless busyness and stress of the big cities. They chose Baroque Salzburg as a place that had remained impervious to more modern priorities and predilections. And I do think the festival harkens back to more medieval days when daily work was punctuated by communal days of pageantry– including games, music, morality plays and church bells. But the founders in trying to resist our modern rat race of endless production and consumption were categorically not trying to harken back to some fossilized point in the past. Not at all. For they called their project an “anti-modern product of modernity.” The festival has always dwelled in the ambiguous realm between “culture” and “modernity”, combining continuity with radical and shocking reinterpretations of beloved cultural artifacts.

And so, I was not surprised to read that the possibility for opening up alternative ways of being was one of the stated objectives of the Salzburg Music Festival when it was first conceived in the early years of the 20th century. Founding fathers of the festival–the Holy Trinity of stage director Max Reinhardt, writer Hugo von Hofmannthal, and composer Richard Strauss– purposively set out to create a festival that would exist far away from the relentless busyness and stress of the big cities. They chose Baroque Salzburg as a place that had remained impervious to more modern priorities and predilections. And I do think the festival harkens back to more medieval days when daily work was punctuated by communal days of pageantry– including games, music, morality plays and church bells. But the founders in trying to resist our modern rat race of endless production and consumption were categorically not trying to harken back to some fossilized point in the past. Not at all. For they called their project an “anti-modern product of modernity.” The festival has always dwelled in the ambiguous realm between “culture” and “modernity”, combining continuity with radical and shocking reinterpretations of beloved cultural artifacts.

Things continue but nothing stays the same.

For example, every year the festival is kicked off with a performance of the same play, the Everyman (Jedermann). Can you imagine for almost a hundred years, every year the same play is performed? And what a play it is. Written by festival founding father Hugo von Hofmannthal, the Everyman is based on a one-act English medieval morality play about the perils of greed. Performed outside of Salzburg’s main cathedral, the play is timed to end as the sun sinks down behind the cathedral’s famous dome to the sound of church bells. Here, the theme of greed and extreme wealth are acted out for concert-goers. (Tickets for the play range from $12-$205).

It is as if the entire city has been transformed into a giant stage. In addition to the cathedral square, performances take place in churches and theaters around town with the main venue being the festivals halls located in the four-hundred-year-old summer and winter riding schools of the old Prince-Archbishops. Interesting to remember that Salzburg was not part of the Habsburg Empire, instead having been ruled as an independent church state for eleven centuries. The city has indeed long stood as a world apart.

My own favorite venue is the once summer riding school (the Felsenreitschule). The hall started off as the place where the prince-archdukes would watch their stallions performing in great Baroque pageantry from one of the ninety loggias that had been cut directly into the mountain to create this “riding school in the rock.” The loggias are now used as a backdrop to the stage, where beloved operas, as well as avant-garde and cutting-edge new works are performed. During our tour of the festival halls, technicians were preparing for the evening’s performance of Hans Werner Henze’s The Bassarids (another kind of one-act morality play that was commissioned by the festival and first performed there in 1966). We were not planning to see the performance, but my husband became so enraptured by the sight of the ultra-modern stage setting against the antique loggias, that on an impulse he bought two tickets. He said that tickets ranged somewhere between $14-$400! Bravo Austria for supporting the arts!

My own favorite venue is the once summer riding school (the Felsenreitschule). The hall started off as the place where the prince-archdukes would watch their stallions performing in great Baroque pageantry from one of the ninety loggias that had been cut directly into the mountain to create this “riding school in the rock.” The loggias are now used as a backdrop to the stage, where beloved operas, as well as avant-garde and cutting-edge new works are performed. During our tour of the festival halls, technicians were preparing for the evening’s performance of Hans Werner Henze’s The Bassarids (another kind of one-act morality play that was commissioned by the festival and first performed there in 1966). We were not planning to see the performance, but my husband became so enraptured by the sight of the ultra-modern stage setting against the antique loggias, that on an impulse he bought two tickets. He said that tickets ranged somewhere between $14-$400! Bravo Austria for supporting the arts!

We bought very reasonably priced tickets for what were fantastic seats and delighted as the enormous spectacle unfolded in front of our eyes–there was a massive orchestra and chorale, each with a conductor, with the percussion section in a completely different part of the hall. I would wager there were two hundred artists performing that night. This was our first performance of the festival, and I could not help but notice how international the audience was. And that the hall was packed (with cheaper seats and expensive seats sold out). An extremely serious and attentive audience–it was nice to see how the terrible corporatization of music has not taken over the Salzburg festival. Artistic choices were made by artists, not corporate sponsors or politicians. Looking around, I thought of poor Princess Wittgenstein who once lamented how things have gone downhill since the heyday of van Karajan, when Salzburg was jet-set ground zero. “Now, you are lucky if the person sitting next to you is not in blue jeans…”

The next evening was also exciting with many Chinese attendees there to see Yuja Wang performing with the Berlin Philharmonic with their new chief conductor, Kirill Petrenko. Held in the newer Large Festival Hall (Großes Festspielhaus) located adjacent to the summer riding school, I couldn’t help but notice someone in a red baseball cap during the intermission. Could it be? Again, my mind turned to poor Princess Wittgenstein! And finally, you might be wondering if there was a winter riding school (since there is a summer riding school). Yes, and it has been renovated and turned into the House for Mozart (“Haus für Mozart”). And this is where we saw the show that I had flown all that way from LA to see: Monteverdi’s “L’Incoronazione di Poppea.” My favorite opera of all time, American mezzo Kate Lindsay played Nero. Her last duet with soprano Sonya Yoncheva (see below) had me in tears. It was a moment I could easily dwell in for eternity.

The next evening was also exciting with many Chinese attendees there to see Yuja Wang performing with the Berlin Philharmonic with their new chief conductor, Kirill Petrenko. Held in the newer Large Festival Hall (Großes Festspielhaus) located adjacent to the summer riding school, I couldn’t help but notice someone in a red baseball cap during the intermission. Could it be? Again, my mind turned to poor Princess Wittgenstein! And finally, you might be wondering if there was a winter riding school (since there is a summer riding school). Yes, and it has been renovated and turned into the House for Mozart (“Haus für Mozart”). And this is where we saw the show that I had flown all that way from LA to see: Monteverdi’s “L’Incoronazione di Poppea.” My favorite opera of all time, American mezzo Kate Lindsay played Nero. Her last duet with soprano Sonya Yoncheva (see below) had me in tears. It was a moment I could easily dwell in for eternity.

And I am still shivering from delight!!

Madeleine l’Engle once said that, “A book, too, can be a star, ‘explosive material, capable of stirring up fresh life endlessly,’ a living fire to lighten the darkness, leading out into the expanding universe.” The founders of the Salzburg Festival had wanted that explosive quality–that same magical something– to light up the darkness of the world; for they believed that culture had the power to bring people together in times of darkness. Maybe the founders were naive to put such faith in art and culture. But traveling to Salzburg, I realized that culture does have the power to gather people and allow them to step outside of ordinary time (like the festivals of old) and experience something bigger than themselves. Remembering cherry blossom viewing parties and tea gatherings; festivals and moon-viewings, for me, Salzburg was an unforgettable and unrepeatable moment that “stirs up fresh life.” To inhabit the thrilling space where creative experimentation and freedom of thought reigns, and to join with people who travel from afar in order to submit to the shared, transforming power of great art…for me, it doesn’t get any better than this.

***

~~ For Brooks, Thank you for being there every step of the way!

***

NYT Reviews: ‘Everyman’ Anchors Drama at the Salzburg Festival & Is ‘The Bassarids’ an Operatic Masterpiece, or ‘Strauss Turned Sour’?

At Salzburg, an Unlikely Operatic Trio of Women Finding Their Way

In a Wagnerian Whirlwind, One Conductor Breaks Through

About Tony Palmer’s fantastic documentary about the Festival: The Nazis and the Salzburg Festival: A Disputed Film History