by Steve Gardner

Magnus Carlsen and Fabiano Caruana faced off for the World Chess Championship over three weeks London. I’d been looking forward to the match all year, and following the progress of the two players towards it. This piece looks at the two players and the situation before the match, gives an account of the Championship games, and concludes with some reflections on the significance of the match for the participants, and for the sport.

Magnus Carlsen and Fabiano Caruana faced off for the World Chess Championship over three weeks London. I’d been looking forward to the match all year, and following the progress of the two players towards it. This piece looks at the two players and the situation before the match, gives an account of the Championship games, and concludes with some reflections on the significance of the match for the participants, and for the sport.

Before the Match

The Challenger – Fabiano Caruana

Caruana is the toughest test Carlsen has yet faced in a World Championship match: more creative and dangerous in attack than the stolid defensive master Sergey Karjakin, and younger and more formidable even than the great Vishy Anand, who, while he was one the greatest players of his generation, was well into his forties and past the peak of his playing strength in the two world championship matches he played against Carlsen in 2013 and 2014. Caruana had a poor start to the year at the Tata Steel tournament in Wijk aan Zee in January, but since then he has been in utterly brilliant form, winning not only the Candidates tournament in March to earn his right to play this match, but also the Grenke Chess Classic in April, the Norway Chess tournament in June, and (jointly with Carlsen and Aronian), the Sinquefield Cup in August. He also finished second in the US Championship. This sustained run of strong chess has seen his rating rise from 2799 at the end of 2017 to 2832, within 3 points of Carlsen, a statistical near-tie; this is the first time since Carlsen’s rise to the top of the chess rankings in 2012 that any player has been so close to him in rating. A single victory by Caruana during the match would see him overtake Carlsen and become the #1-ranked player in the world.

The Champion – Magnus Carlsen

Carlsen’s form in 2018 was slightly less impressive, though by no means bad. He won the Tata Steel tournament in January, the Fischer Random World Championship in February (defeating Hikaru Nakamura), the Shamkir Chess tournament in April, and as mentioned above shared first place in the Sinquefield Cup in August. He’s played many beautiful games in his characteristic boa constrictor style, squeezing out wins in long games out of technical endgame positions, including a memorable victory over Nakamura in the last round of the Sinquefield Cup, demonstrating a beautiful winning idea. But this year we have also seen some cracks appear in his normally impregnable composure, an un-Magnus-like indecisiveness at key moments, opponents allowed to escape lost positions, such as his game with Caruana at the Sinquefield Cup where Magnus misplayed a winning attack and Caruana escaped with a draw. His rating going into the match of 2835 had scarcely changed this year; if it hadn’t risen like Caruana’s, just maintaining a rating at these stratospheric heights is an impressive achievement. Still, Carlsen’s peak rating of 2882 (the highest ever by any human player) was achieved in May 2014, and is nearly 50 points higher than his rating now. So questions were in the air which the course of the match would amplify: what are the reasons for Carlsen’s rating decline? Would he be able to bring his best game to the match? And if not, would that be enough to keep Caruana at bay? Read more »

In the middle of the night of March 24, 1992, a pressure seal failed in the number three unit of the Leningradskaya Nuclear Power Plant at Sosnoviy Bor, Russia, releasing radioactive gases. With a friend, I had train tickets from Tallinn, in newly independent Estonia, to St. Petersburg the next day. That would take us within twenty kilometers of the plant. The legacy of Soviet management at Chernobyl a few years before set up a fraught decision whether or not to take the train.

In the middle of the night of March 24, 1992, a pressure seal failed in the number three unit of the Leningradskaya Nuclear Power Plant at Sosnoviy Bor, Russia, releasing radioactive gases. With a friend, I had train tickets from Tallinn, in newly independent Estonia, to St. Petersburg the next day. That would take us within twenty kilometers of the plant. The legacy of Soviet management at Chernobyl a few years before set up a fraught decision whether or not to take the train. It’s been a while since I posted on this issue, and I’ve already said most of what I intended to say about it, but things seem to be coming to a head in my own state, and I thought I’d report on that, including a couple of weird local wrinkles (the Garden State is a strange place). Three weeks ago, after months of missed deadlines, an adult-use marijuana legalization bill was approved by a joint (Assembly/Senate, that is, not … never mind) committee of the legislature, and may (note: may) be voted on later this year. If it is passed and signed into law by the governor – neither of which is a given – New Jersey would be the eleventh state to legalize adult use, and the second to do so by legislative action. (Washington and Colorado in 2012, Alaska and Oregon in 2014, California, Massachusetts, Maine, and Nevada in 2016, and Michigan in 2018 did so by voter referendum; Vermont did so by legislative action (in 2017, I think), although that state’s bill did not set up a legal market, which means that while it is legal to grow marijuana in one’s basement there, it remains illegal to buy seeds to do so.)

It’s been a while since I posted on this issue, and I’ve already said most of what I intended to say about it, but things seem to be coming to a head in my own state, and I thought I’d report on that, including a couple of weird local wrinkles (the Garden State is a strange place). Three weeks ago, after months of missed deadlines, an adult-use marijuana legalization bill was approved by a joint (Assembly/Senate, that is, not … never mind) committee of the legislature, and may (note: may) be voted on later this year. If it is passed and signed into law by the governor – neither of which is a given – New Jersey would be the eleventh state to legalize adult use, and the second to do so by legislative action. (Washington and Colorado in 2012, Alaska and Oregon in 2014, California, Massachusetts, Maine, and Nevada in 2016, and Michigan in 2018 did so by voter referendum; Vermont did so by legislative action (in 2017, I think), although that state’s bill did not set up a legal market, which means that while it is legal to grow marijuana in one’s basement there, it remains illegal to buy seeds to do so.) I met Rene Magritte a few weeks ago at the Starline Social Club in Oakland. A surprisingly jolly fellow, it turns out he’s working these days as a pedicab driver in San Francisco. Surrealism isn’t my jam, but when he offered me a pickup the next morning at the BART and mushrooms and tickets for two to the retrospective of his work at SFMoMA, well—I had to accept.

I met Rene Magritte a few weeks ago at the Starline Social Club in Oakland. A surprisingly jolly fellow, it turns out he’s working these days as a pedicab driver in San Francisco. Surrealism isn’t my jam, but when he offered me a pickup the next morning at the BART and mushrooms and tickets for two to the retrospective of his work at SFMoMA, well—I had to accept.

Magnus Carlsen and Fabiano Caruana faced off for the World Chess Championship over three weeks London. I’d been looking forward to the match all year, and following the progress of the two players towards it. This piece looks at the two players and the situation before the match, gives an account of the Championship games, and concludes with some reflections on the significance of the match for the participants, and for the sport.

Magnus Carlsen and Fabiano Caruana faced off for the World Chess Championship over three weeks London. I’d been looking forward to the match all year, and following the progress of the two players towards it. This piece looks at the two players and the situation before the match, gives an account of the Championship games, and concludes with some reflections on the significance of the match for the participants, and for the sport. I recently rewatched “12 Angry Men” with The Philosophy Club at the University of Iowa as part of their “Owl of Minerva” film series. The 1957 film has the late, great Henry Fonda as the lone holdout on a jury ready to convict a poor, abused 18-year-old boy for allegedly stabbing his father to death. Over one long, tense evening (shown in something close to real-time), juror #8 – none of the jurors are identified by name, only number – forces the rest of the jury to methodically reexamined the evidence. It’s not a courtroom drama, it’s a jury-room drama in which only 3 of 1:36 minutes of running time take place outside the sweaty, claustrophobic jury room. The film is intense, moving, and effective. Afterwards, I made the following remarks.

I recently rewatched “12 Angry Men” with The Philosophy Club at the University of Iowa as part of their “Owl of Minerva” film series. The 1957 film has the late, great Henry Fonda as the lone holdout on a jury ready to convict a poor, abused 18-year-old boy for allegedly stabbing his father to death. Over one long, tense evening (shown in something close to real-time), juror #8 – none of the jurors are identified by name, only number – forces the rest of the jury to methodically reexamined the evidence. It’s not a courtroom drama, it’s a jury-room drama in which only 3 of 1:36 minutes of running time take place outside the sweaty, claustrophobic jury room. The film is intense, moving, and effective. Afterwards, I made the following remarks.

It’s getting colder now in Beijing, and I can’t help but feel for the clothing left outside to dry. They had to hang through the night and on through the weak sunrise, doing their best to catch the wind before the temperature drops again. How do they feel being out there for passers-by to see, all exposed, caught up in the dust and very small toxic particles?

It’s getting colder now in Beijing, and I can’t help but feel for the clothing left outside to dry. They had to hang through the night and on through the weak sunrise, doing their best to catch the wind before the temperature drops again. How do they feel being out there for passers-by to see, all exposed, caught up in the dust and very small toxic particles?

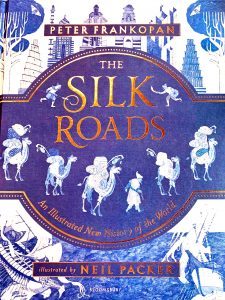

“You start with a scarf…each 90-by-90-centimeter silk carré, printed in Lyon on twill made from thread created by the label’s own silkworms, holds a story. Since 1937, almost 2,500 original artworks have been produced, such as a 19th-century street scene from Ruedu Faubourg St.-Honore, the company’s home since 1880. The flora and fauna of Texas. A beach in Spain’s Basque country” –- this is a fragment from an advertisement article for Hermès in this month’s issue of a luxury magazine. The article is called “The Silk Road.” Does it refer to the “Silk Road” in any way that justifies the title, beyond the allure of legend? No. Does it mention that the first scarves created for this very label, in 1937, were made with raw silk from China? No. Not necessary, not relevant to the target reader. In fact, the less we mention the “East” while trying to sell such luxury designer items, the better, aiming as we are for the rich collector, the global consumer of fashion (whether belonging to the East or West) willing to spend hundreds of dollars on a small square of silk, and more likely to associate such status symbols with Western Europe rather than with the “underdeveloped,” impoverished, overpopulated, conflict-ridden East.

“You start with a scarf…each 90-by-90-centimeter silk carré, printed in Lyon on twill made from thread created by the label’s own silkworms, holds a story. Since 1937, almost 2,500 original artworks have been produced, such as a 19th-century street scene from Ruedu Faubourg St.-Honore, the company’s home since 1880. The flora and fauna of Texas. A beach in Spain’s Basque country” –- this is a fragment from an advertisement article for Hermès in this month’s issue of a luxury magazine. The article is called “The Silk Road.” Does it refer to the “Silk Road” in any way that justifies the title, beyond the allure of legend? No. Does it mention that the first scarves created for this very label, in 1937, were made with raw silk from China? No. Not necessary, not relevant to the target reader. In fact, the less we mention the “East” while trying to sell such luxury designer items, the better, aiming as we are for the rich collector, the global consumer of fashion (whether belonging to the East or West) willing to spend hundreds of dollars on a small square of silk, and more likely to associate such status symbols with Western Europe rather than with the “underdeveloped,” impoverished, overpopulated, conflict-ridden East. A few months back my boss and I had lunch with the person who, wearing a t-shirt that read “black death spectacle”, stood in protest in front of a painting of Emmett Till by Dana Schutz called Open Casket at the last Whitney Biennial. Shortly after his gesture another artist penned an open letter about how Schutz’s painting uses “black pain” as a medium, and how this use by non-Black artists needs to go. I’m not sure what the ethical verdict is (of whether or not Schutz made a gravely racist error), or whether the artist’s letter voiced an instance of over-reaching aesthetic censorship, nor will I make any attempt at trying to resolve that issue here; it would take far more space than what is available and is not my aim. Consider reading Aruna D’Souza’s recent book Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts for a thorough treatment (which, not so incidentally, the above mentioned protestor provided images for).

A few months back my boss and I had lunch with the person who, wearing a t-shirt that read “black death spectacle”, stood in protest in front of a painting of Emmett Till by Dana Schutz called Open Casket at the last Whitney Biennial. Shortly after his gesture another artist penned an open letter about how Schutz’s painting uses “black pain” as a medium, and how this use by non-Black artists needs to go. I’m not sure what the ethical verdict is (of whether or not Schutz made a gravely racist error), or whether the artist’s letter voiced an instance of over-reaching aesthetic censorship, nor will I make any attempt at trying to resolve that issue here; it would take far more space than what is available and is not my aim. Consider reading Aruna D’Souza’s recent book Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts for a thorough treatment (which, not so incidentally, the above mentioned protestor provided images for).

Ever since my childhood I have been excited, even electrified, by movies. In my college days in Calcutta, in search of alternate experience beyond Indian and Hollywood movies, I used to frequent the local Film Society events, showing some commercially unavailable European fare. Short of funds these Film Society outfits mainly went for movies they could procure at low cost. The East European consulates in the city were particularly generous in making available films from their countries.

Ever since my childhood I have been excited, even electrified, by movies. In my college days in Calcutta, in search of alternate experience beyond Indian and Hollywood movies, I used to frequent the local Film Society events, showing some commercially unavailable European fare. Short of funds these Film Society outfits mainly went for movies they could procure at low cost. The East European consulates in the city were particularly generous in making available films from their countries.