FDR? You mean Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 32d president of the USofA?

FDR? You mean Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 32d president of the USofA?

Not quite. I mean FDR SK8park, in Philadelphia.

“SK8park”? What’s that? Can’t you spell?

Yes I can. Sound it out.

Oh, you mean “skate park”.

Right. SK8park, FDR SK8park. It’s at the southern end of Franklin Delano Park.

What’s this skateboard nation?

It’s a notion, if you will, a conceit, a turn of phrase, a way of speaking. Perhaps, if you will, an identity of sorts. And that’s what this is about.

The do-it-yourself “spot” or park is one facet of skateboarding. A bunch of skateboarders will find an out-of-the-way spot and remake it to their purposes, installing rails, half-pipes, banks, pyramids, and other features. Some of these are fairly small, like the one I ran into some years ago in Jersey City when I was photographing graffiti. Others are quite large, like Philly’s FDR, which is one of the largest and best-known DIY parks in the world.

FDR is festooned with graffiti and street art. Most of it is a grab-bag of standard stuff, tags, throw-ups, pieces of varying quality, posters and stickers and what have you. But some of it is of a different nature. That’s what I’m interested in.

As you read this, think of yourself as an explorer, an archeologist perhaps – Indiana Jones? You’ve come across a strange civilization. You’ve talked with a native or two, but mostly you’re examining the markings they’ve made. What do they mean?

Consider the photo at the right (from 2014). Up at the top it says “THIS IS LIVIN’”. Whatever ‘this’ is that, presumably, is what we see these two people doing, skate boarding. And they’re passionate about it. Read more »

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

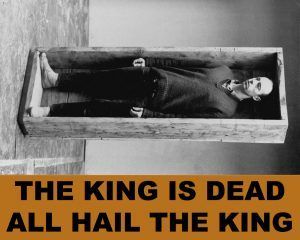

Robert Morris died last month on November 28th at the ripe old age of 87. Very ripe indeed. If he was a fig he’d have been all jammy inside, dribbling the honeyed sugars of maturation. But he’s dead, and I’m glad he’s dead. Let me step back before explaining why – this isn’t an exposition, this is an obituary; I’m grieving; this is diffused ramblings at a podium. I went to Hunter College for undergraduate philosophy and flirted with the art department quite a bit. Morris’ legacy loomed large and hard over the department as he had both attended grad school and taught there. Any course in the art department was bound to encounter his work or his writings. I must have been assigned “Notes on Sculpture” a dozen times. Morris was, and still is, a great artist. His was a scholarly brand of art; neither annoying like Joseph Kosuth, nor dehydrated like Hans Haacke. No, Morris was a genuine student of art and thought. He studied its history, wrote about it emphatically, and contributed to its heritage. It is not difficult to view him as one of the several pillars that contemporary art stands upon today, and feel indebted to his legacy. One of his first well regarded artworks was Box for Standing, which was a handmade wooden box roughly the size of a coffin that fit Morris neatly. How fitting then, that his exit from this life should perhaps be in a box bespoke for his corpse, roughly the same size as his original Box? His expiration has a funny effect on that work, Box for Standing, where his actual death gives the work one last veneer of meaning to stack upon all the other layers. One might have seen similarity between the Box for Standing and funerary vessels before Morris died, but afterward it would be reckless not to see it. The work goes from being a sparse theatrical gesture contained in minimal sculpture, to something like a pragmatic Quaker coffin, verging on bleak humor.

Robert Morris died last month on November 28th at the ripe old age of 87. Very ripe indeed. If he was a fig he’d have been all jammy inside, dribbling the honeyed sugars of maturation. But he’s dead, and I’m glad he’s dead. Let me step back before explaining why – this isn’t an exposition, this is an obituary; I’m grieving; this is diffused ramblings at a podium. I went to Hunter College for undergraduate philosophy and flirted with the art department quite a bit. Morris’ legacy loomed large and hard over the department as he had both attended grad school and taught there. Any course in the art department was bound to encounter his work or his writings. I must have been assigned “Notes on Sculpture” a dozen times. Morris was, and still is, a great artist. His was a scholarly brand of art; neither annoying like Joseph Kosuth, nor dehydrated like Hans Haacke. No, Morris was a genuine student of art and thought. He studied its history, wrote about it emphatically, and contributed to its heritage. It is not difficult to view him as one of the several pillars that contemporary art stands upon today, and feel indebted to his legacy. One of his first well regarded artworks was Box for Standing, which was a handmade wooden box roughly the size of a coffin that fit Morris neatly. How fitting then, that his exit from this life should perhaps be in a box bespoke for his corpse, roughly the same size as his original Box? His expiration has a funny effect on that work, Box for Standing, where his actual death gives the work one last veneer of meaning to stack upon all the other layers. One might have seen similarity between the Box for Standing and funerary vessels before Morris died, but afterward it would be reckless not to see it. The work goes from being a sparse theatrical gesture contained in minimal sculpture, to something like a pragmatic Quaker coffin, verging on bleak humor.  In reviewing “Intimations of Ghalib”, a new translation of selected ghazals of the Urdu poet Ghalib by M. Shahid Alam, let it be said at the outset that translating classical Urdu ghazal into any language – possibly excepting Persian – is an almost impossible task, and translating Ghalib’s ghazals even more so. The use of symbolism, the aphoristic aspect of each couplet, the frequent play on words, and the packing of multiple meanings into a single verse are all too easy to lose in translation. And no Urdu poet used all these devices more pervasively and subtly than Ghalib, and even learned scholars can disagree strongly on the “correct” meaning of particular verses. As such, Alam set himself an impossible task, and the result is, among other things, a demonstration of this.

In reviewing “Intimations of Ghalib”, a new translation of selected ghazals of the Urdu poet Ghalib by M. Shahid Alam, let it be said at the outset that translating classical Urdu ghazal into any language – possibly excepting Persian – is an almost impossible task, and translating Ghalib’s ghazals even more so. The use of symbolism, the aphoristic aspect of each couplet, the frequent play on words, and the packing of multiple meanings into a single verse are all too easy to lose in translation. And no Urdu poet used all these devices more pervasively and subtly than Ghalib, and even learned scholars can disagree strongly on the “correct” meaning of particular verses. As such, Alam set himself an impossible task, and the result is, among other things, a demonstration of this.

In 2018, Earth picked up about 40,000 metric tons of interplanetary material, mostly dust, much of it from comets. Earth lost around 96,250 metric tons of hydrogen and helium, the lightest elements, which escaped to outer space. Roughly 505,000 cubic kilometers of water fell on Earth’s surface as rain, snow, or other types of precipitation. Bristlecone pines, which can live for millennia, each gained perhaps a hundredth of an inch in diameter. Countless mayflies came and went. As of this writing, more than one hundred thirty-six million people were born in 2018, and more than fifty-seven million died.

In 2018, Earth picked up about 40,000 metric tons of interplanetary material, mostly dust, much of it from comets. Earth lost around 96,250 metric tons of hydrogen and helium, the lightest elements, which escaped to outer space. Roughly 505,000 cubic kilometers of water fell on Earth’s surface as rain, snow, or other types of precipitation. Bristlecone pines, which can live for millennia, each gained perhaps a hundredth of an inch in diameter. Countless mayflies came and went. As of this writing, more than one hundred thirty-six million people were born in 2018, and more than fifty-seven million died.

It is simultaneously awkward and exciting to read about your own consciously and responsibly adopted beliefs as something to be anatomized. It is also something atheists are not always much disposed to. On the contrary, perhaps: many forms of atheism present themselves as a consequence of free thought, of emancipation from tradition. The internal logic of their arguments prescribes that while religious beliefs, being non-rational, are in need of cultural or psychological explanation, atheism is really just what you will gravitate towards once you finally start thinking. One question here will be whether this is necessarily the case.

It is simultaneously awkward and exciting to read about your own consciously and responsibly adopted beliefs as something to be anatomized. It is also something atheists are not always much disposed to. On the contrary, perhaps: many forms of atheism present themselves as a consequence of free thought, of emancipation from tradition. The internal logic of their arguments prescribes that while religious beliefs, being non-rational, are in need of cultural or psychological explanation, atheism is really just what you will gravitate towards once you finally start thinking. One question here will be whether this is necessarily the case. Certain phrases choke us with their ubiquity at some point:

Certain phrases choke us with their ubiquity at some point: