by Adele A Wilby

Many decades ago, I packed my bags and left the shores of Australia and headed to the United Kingdom (UK). My secondary years of education had taught me to believe that my journey to the UK would amount to a ‘return’ to the ‘motherland’. A ‘return to the motherland’? Really? That says more about the education system I was exposed to, than just how naïve I was. However, having learned after my arrival that the UK was not, in fact, my ‘motherland’, I did discern that it had more to offer in terms of being ‘in’ the world than the distant shores of Australia, and I decided to stay. Thus, after many years resident in the UK, I considered myself as someone familiar with the country, until, that is, a change in my life circumstances provided me the opportunity to know the UK, or more specifically, England, in a totally different way.

Many decades ago, I packed my bags and left the shores of Australia and headed to the United Kingdom (UK). My secondary years of education had taught me to believe that my journey to the UK would amount to a ‘return’ to the ‘motherland’. A ‘return to the motherland’? Really? That says more about the education system I was exposed to, than just how naïve I was. However, having learned after my arrival that the UK was not, in fact, my ‘motherland’, I did discern that it had more to offer in terms of being ‘in’ the world than the distant shores of Australia, and I decided to stay. Thus, after many years resident in the UK, I considered myself as someone familiar with the country, until, that is, a change in my life circumstances provided me the opportunity to know the UK, or more specifically, England, in a totally different way.

Acting on the advice of a friend concerned with what he considered to be my solitary life following the death of my husband, I joined the Ramblers’ Association in the UK. Involvement with activities of the Ramblers didn’t last too long; group walking was not my thing. I did learn however, that walking was something I relished; it literally, put a spring in my step. The more regularly I walked the more the country opened up to me, an England loaded with complexity, diversity, mystery, and an alluring, limitless beauty: the English countryside.

In many ways, the countryside is how England can be: cold and aloof, requiring time to get to know; a place where one can feel a sojourner in its midst; a place where its nuances and secrets take time to understand. But it is too a place that tolerates your presence, and, as long as you remain respectful, it will allow you to saunter and relish the attributes that it has to offer, undisturbed and secure. That, to me, is fair enough; I don’t ask for more. I have no wish to disturb its existence, or indeed, undermine any aspect of its life.

The UK is exceptional for its network of public footways and bridleways; walking routes where ramblers are permitted to cross farmers’ property, to pass through private driveways and gardens and around farm buildings, if that is where the public right of way takes its direction. Read more »

We can agree that a verb in the present tense means that action is occurring now. What about the present progressive, which I used in the previous statement? That apparently confounds non-native English speakers because it means that an action is in the middle of happening. Friends have asked me, “What is the difference between I am playing tennis and I play tennis?” That example is actually a softball because the present progressive indicates that the first person is in the middle of playing a game and the simple present indicates the playing of the sport in general.

We can agree that a verb in the present tense means that action is occurring now. What about the present progressive, which I used in the previous statement? That apparently confounds non-native English speakers because it means that an action is in the middle of happening. Friends have asked me, “What is the difference between I am playing tennis and I play tennis?” That example is actually a softball because the present progressive indicates that the first person is in the middle of playing a game and the simple present indicates the playing of the sport in general. Before the second was defined in terms of the characteristics of the cesium atom, before leap seconds or leap days or Julian dates or the Gregorian calendar, before clocks, even before the sundial and the hourglass, there were sunrise, sunset, and shadows.

Before the second was defined in terms of the characteristics of the cesium atom, before leap seconds or leap days or Julian dates or the Gregorian calendar, before clocks, even before the sundial and the hourglass, there were sunrise, sunset, and shadows. The fall turned colors faster than ever before. The streets never saw any activity. The whole gambit of Prometheus hinged on a mere coin flip. Richard Albrook gingerly closed his book and took a look around.

The fall turned colors faster than ever before. The streets never saw any activity. The whole gambit of Prometheus hinged on a mere coin flip. Richard Albrook gingerly closed his book and took a look around.

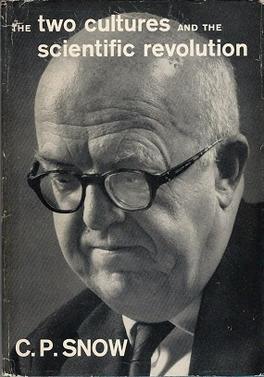

It is a commonplace to say that a divide has occurred in modern academia between the sciences and the humanities. In the anglophone world, this diagnosis is often traced back to a lecture by the British scientist-novelist Charles Snow, who pointed out in 1959 what he saw as a lamentable gap between ‘two cultures’: the literary and the scientific culture. Snow’s Rede lecture has become the main

It is a commonplace to say that a divide has occurred in modern academia between the sciences and the humanities. In the anglophone world, this diagnosis is often traced back to a lecture by the British scientist-novelist Charles Snow, who pointed out in 1959 what he saw as a lamentable gap between ‘two cultures’: the literary and the scientific culture. Snow’s Rede lecture has become the main

“Beware of literature!” This warning occurs in Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1938 novel Nausea as an entry in the diary of the narrator, Antoine Roquentin. In context, it concerns the way that literary narratives falsify our experience of events by investing them with an organization and structure that our experiences in themselves, as we live them, do not have. When Bilbo Baggins finds the ring in The Hobbit, Tolkein tells us that although Bilbo didn’t realize it at the time, this would turn out to be a turning point in his life. When married couples recall their first meeting, their account inevitably packages the event as a “beginning,” even though they may have had no inkling of this at the time.

“Beware of literature!” This warning occurs in Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1938 novel Nausea as an entry in the diary of the narrator, Antoine Roquentin. In context, it concerns the way that literary narratives falsify our experience of events by investing them with an organization and structure that our experiences in themselves, as we live them, do not have. When Bilbo Baggins finds the ring in The Hobbit, Tolkein tells us that although Bilbo didn’t realize it at the time, this would turn out to be a turning point in his life. When married couples recall their first meeting, their account inevitably packages the event as a “beginning,” even though they may have had no inkling of this at the time. Do you find this prospect upsetting? Perhaps you think it is unfair for someone to get a job without a good reason for why they deserve it rather than anyone else. Perhaps you think such a system would decrease your chances of getting the job you want. If so then you may be under the influence of the cult of excellence.

Do you find this prospect upsetting? Perhaps you think it is unfair for someone to get a job without a good reason for why they deserve it rather than anyone else. Perhaps you think such a system would decrease your chances of getting the job you want. If so then you may be under the influence of the cult of excellence.