by Brooks Riley

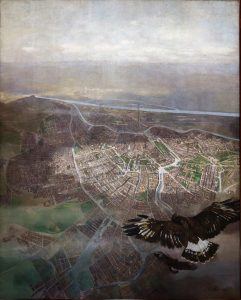

When architect Otto Wagner commissioned this large painting by Carl Moll for the Kaiser’s personal railroad station in Vienna in 1899, he might not have seen the irony of an eagle’s view of the city. View of Vienna from a Balloon envisions a future beyond rails in which a bird shows the way to a whole new way of looking at landscape, one that would renew the way we view nature itself, hardly more than a 100 years later. If that painting were done today, the eagle would be replaced by a small four-cornered device with a camera and four rotary blades to keep it aloft: the drone.

When architect Otto Wagner commissioned this large painting by Carl Moll for the Kaiser’s personal railroad station in Vienna in 1899, he might not have seen the irony of an eagle’s view of the city. View of Vienna from a Balloon envisions a future beyond rails in which a bird shows the way to a whole new way of looking at landscape, one that would renew the way we view nature itself, hardly more than a 100 years later. If that painting were done today, the eagle would be replaced by a small four-cornered device with a camera and four rotary blades to keep it aloft: the drone.

The relationship between human beings and nature has always been tense. While we acknowledge our debt to nature—our existence, our food, building materials, environment, panoramic views, flora and fauna, chromatic infinity, physical and biological laws—there is always some corner of our thinking that cries out, ‘Anything you can do I can do better,’ to quote an Irving Berlin song. When it comes to art, we set ourselves on a collision course with nature, touting our museum landscapes over the real ones and the painter’s vision as the one true aesthetic version of beauty. Now that we’ve left nature behind (in more ways than one), nature has left the building and moved into the brand new Instagram showroom where it can show itself off with impunity from interpretation.

The recognition of nature as a generator of beauty is universal. Representational art and photography are often tributes to that beauty—pyrrhic undertakings when the original is so compelling. And yet careers have been made from the depiction of nature—Caspar David Friedrich, Ansel Adams, and countless others. If our art differs from nature, it is in the selectivity and execution of the image as much as it is the subject matter. Art is our way of saying to nature, we can do better than you. Read more »

This year – 2018 – marks something truly auspicious. This is the semi-centennial of the invention of the Zombie. In these fifty years, let’s face it, we have been completely overrun. Zombies are everywhere. They are in our movies, tv shows, books, and comic books, plus, out here in the real world where the Center for Disease Control has a comprehensive Zombie preparedness and education plan and there are Zombie-walks, Zombie-conventions, and, anyway, didn’t you see them this Halloween? The most popular Zombie tv show, “The Walking Dead”, has been streaming for almost ten years – and the comic book it is based on is still going strong. At least one Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winning author has written a straight-up zombie novel – Colson Whitehead’s “Zone One”. So, what’s with all the Zombies?

This year – 2018 – marks something truly auspicious. This is the semi-centennial of the invention of the Zombie. In these fifty years, let’s face it, we have been completely overrun. Zombies are everywhere. They are in our movies, tv shows, books, and comic books, plus, out here in the real world where the Center for Disease Control has a comprehensive Zombie preparedness and education plan and there are Zombie-walks, Zombie-conventions, and, anyway, didn’t you see them this Halloween? The most popular Zombie tv show, “The Walking Dead”, has been streaming for almost ten years – and the comic book it is based on is still going strong. At least one Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winning author has written a straight-up zombie novel – Colson Whitehead’s “Zone One”. So, what’s with all the Zombies?

“They all go the same way. Look up, then down and to the left,” the EMT said. “Always.”

“They all go the same way. Look up, then down and to the left,” the EMT said. “Always.”

In Tian Shan mountains of the legendary snow leopard, errant wisps of mist float with the speed of scurrying ghosts, there is a climbers’ cemetery, Himalayan Griffin vultures and golden eagles are often sighted, though my attention is completely arrested by a Blue whistling thrush alighting on a rock— its plumage, its slender, seemingly weightless frame, and its long drawn, ventriloquist song remind me of the fairies of Alif Laila that were turned to birds by demons inhabiting barren mountains.

In Tian Shan mountains of the legendary snow leopard, errant wisps of mist float with the speed of scurrying ghosts, there is a climbers’ cemetery, Himalayan Griffin vultures and golden eagles are often sighted, though my attention is completely arrested by a Blue whistling thrush alighting on a rock— its plumage, its slender, seemingly weightless frame, and its long drawn, ventriloquist song remind me of the fairies of Alif Laila that were turned to birds by demons inhabiting barren mountains.

On a recent windy morning, walking past the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument on West 89th Street in New York City, seeing the flag at half mast, just days before the

On a recent windy morning, walking past the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument on West 89th Street in New York City, seeing the flag at half mast, just days before the  April 2018: ‘Tis the Season of Giddiness in Democratlandia. Republicans are saddled with a widely despised President and riven by internal dissension. The Republican leadership in Congress is lurching from fiasco to fiasco – interrupted briefly by one great “success” on tax cuts. The zombie candidates of the Tea Party are still stalking establishment Republicans across the land. And, somewhere in his formidable fastness, the Great Dragon Mueller is winding up for the fiery breath that will consume the world of Trumpism like a paper lantern. And a Blue Wave – nay, a Tsunami – is headed towards the Republicans in Congress, looking to engulf them in November.

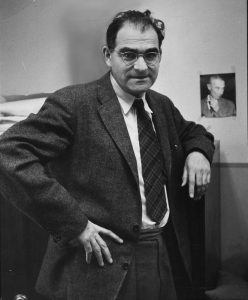

April 2018: ‘Tis the Season of Giddiness in Democratlandia. Republicans are saddled with a widely despised President and riven by internal dissension. The Republican leadership in Congress is lurching from fiasco to fiasco – interrupted briefly by one great “success” on tax cuts. The zombie candidates of the Tea Party are still stalking establishment Republicans across the land. And, somewhere in his formidable fastness, the Great Dragon Mueller is winding up for the fiery breath that will consume the world of Trumpism like a paper lantern. And a Blue Wave – nay, a Tsunami – is headed towards the Republicans in Congress, looking to engulf them in November. Victor Weisskopf (Viki to his friends) emigrated to the United States in the 1930s as part of the windfall of Jewish European emigre physicists which the country inherited thanks to Adolf Hitler. In many ways Weisskopf’s story was typical of his generation’s: born to well-to-do parents in Vienna at the turn of the century, educated in the best centers of theoretical physics – Göttingen, Zurich and Copenhagen – where he learnt quantum mechanics from masters like Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, and finally escaping the growing tentacles of fascism to make a home for himself in the United States where he flourished, first at Rochester and then at MIT. He worked at Los Alamos on the bomb, then campaigned against it as well as against the growing tide of red-baiting in the United States. A beloved teacher and researcher, he was also the first director-general of CERN, a laboratory which continues to work at the forefront of particle physics and rack up honors.

Victor Weisskopf (Viki to his friends) emigrated to the United States in the 1930s as part of the windfall of Jewish European emigre physicists which the country inherited thanks to Adolf Hitler. In many ways Weisskopf’s story was typical of his generation’s: born to well-to-do parents in Vienna at the turn of the century, educated in the best centers of theoretical physics – Göttingen, Zurich and Copenhagen – where he learnt quantum mechanics from masters like Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, and finally escaping the growing tentacles of fascism to make a home for himself in the United States where he flourished, first at Rochester and then at MIT. He worked at Los Alamos on the bomb, then campaigned against it as well as against the growing tide of red-baiting in the United States. A beloved teacher and researcher, he was also the first director-general of CERN, a laboratory which continues to work at the forefront of particle physics and rack up honors.

When you consume a meal, do you eat cow or beef? Yes, these are the same, especially considering where they end up, but we tend to think of the cow as the beginning of this particular process, and the beef as the product. More of these pairings include calf/veal, swine or pig/pork, sheep/mutton, hen or chicken/poultry, deer/venison, snail/escargot.

When you consume a meal, do you eat cow or beef? Yes, these are the same, especially considering where they end up, but we tend to think of the cow as the beginning of this particular process, and the beef as the product. More of these pairings include calf/veal, swine or pig/pork, sheep/mutton, hen or chicken/poultry, deer/venison, snail/escargot.

It could almost be a question on a very meta personality quiz: Do you prefer the Myers-Briggs typology or the Big Five personality traits? The Myers-Brigg Type Inventory is a popular tool that was developed outside of the scientific establishment by two women who did not have credentials in psychology. It’s qualitative rather than quantitative, and in the past decade or so, it’s been criticized as meaningless or unscientific. The Big Five taxonomy is widely accepted in academia and is the basis of much current personality research. It’s quantitative; in fact, it’s based on statistical analysis. Am I rejecting science if I continue to prefer the Myers-Briggs system as a key to understanding my own personality and those of others?

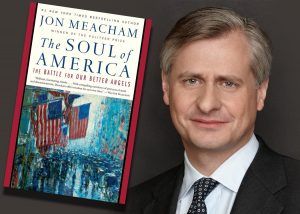

It could almost be a question on a very meta personality quiz: Do you prefer the Myers-Briggs typology or the Big Five personality traits? The Myers-Brigg Type Inventory is a popular tool that was developed outside of the scientific establishment by two women who did not have credentials in psychology. It’s qualitative rather than quantitative, and in the past decade or so, it’s been criticized as meaningless or unscientific. The Big Five taxonomy is widely accepted in academia and is the basis of much current personality research. It’s quantitative; in fact, it’s based on statistical analysis. Am I rejecting science if I continue to prefer the Myers-Briggs system as a key to understanding my own personality and those of others? It is difficult to remember a time over recent decades when a president of the United States (US) has created so much controversy and division within the US and challenged its credibility and standing in international relations as has the incumbent president, Donald Trump. Indeed, so bewildering to many is the election of a former reality TV star and dubious businessman without experience in government, to the high office of president of the US and ‘leader’ of the ‘free’ world, a plethora of literature to account for such a phenomenon has emerged. Similarly, commentaries on evaluations of Trump’s calibre and character, and just how far he is fit for such high office and powerful position in global politics, are plentiful. Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels can be viewed as a contribution to the literature on those issues.

It is difficult to remember a time over recent decades when a president of the United States (US) has created so much controversy and division within the US and challenged its credibility and standing in international relations as has the incumbent president, Donald Trump. Indeed, so bewildering to many is the election of a former reality TV star and dubious businessman without experience in government, to the high office of president of the US and ‘leader’ of the ‘free’ world, a plethora of literature to account for such a phenomenon has emerged. Similarly, commentaries on evaluations of Trump’s calibre and character, and just how far he is fit for such high office and powerful position in global politics, are plentiful. Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels can be viewed as a contribution to the literature on those issues.