by Shawn Crawford

(The following is an excerpt from Crawford’s lecture at the Lausanne, Switzerland conference of The Society of Data Analysts Committed to Reducing Any Complexity to a Single Sobering Graph. Researchers will remember the group’s acrimonious split from the Social Scientists United for Reducing Any Cultural Crisis to a Single Meme. In a classic dispute among the “hard” and “soft” sciences, the two sides exchanged a dizzying array of pie charts and Willie Wonka images with devastating captions to no avail.)

. . . I want to thank Professor Owens once again for his electrifying lecture on determining the outcome of any baseball season by crunching the data from a ten-game sample, reducing the number of games played by 152. Like so much breakthrough research, this also produced an unintended benefit: the freeing up of nearly 10,000 extra hours on TBS for reruns of The Big Bang Theory. I know we are all grateful.

. . . I want to thank Professor Owens once again for his electrifying lecture on determining the outcome of any baseball season by crunching the data from a ten-game sample, reducing the number of games played by 152. Like so much breakthrough research, this also produced an unintended benefit: the freeing up of nearly 10,000 extra hours on TBS for reruns of The Big Bang Theory. I know we are all grateful.

I still remember Professor Owens bursting onto to the scene when his algorithm, pushing the Sunway TaihuLight supercomputer to its limits, proved conclusively that Dewey had indeed defeated Truman. While his subsequent modeling has produced dozens of legislative fixes for this mathematical reality, we know the current gridlock in Washington continues to thwart his efforts.

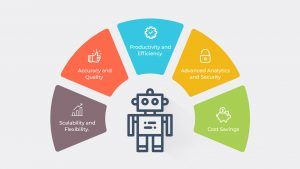

When Dr. Harry Lutz from DataTorrent approached me about joining him on the cutting edge of the Sober Graphing movement, I knew I couldn’t say no. While Thomas Piketty appeared to be rapidly consolidating the research space in Sober Graphing, I reckoned Dr. Lutz had a clear edge moving forward: his proprietary Sober Index, able to finally tackle such vexing questions as does the bar graph illustrating the concentration of wealth since World War II achieve Peak Soberness as it relates to income inequality? Using a baseline of soberness, the realization of just how worthless a degree in the humanities will be, Dr. Lutz built out his Soberness Index with enviable precision.

But would Sober Graphing prove as chimerical as Shocking Graphing and Surprising Graphing in offering real advances? The number of graphs required in these areas had also become problematic: if it’s going to take three scatters, a 2-D pie, and a funnel graph to shock me, perhaps we need to revisit the biases lurking in our data field.

Lutz and I became convinced the Sober Index could help us express the answer to any seemingly intractable question in one elegant, sobering graph. Furthermore, we posited the level of soberness, correctly calibrated to the industry or society addressed, could effect lasting and measurable change. But before we tackled broader issues, we decided to test our hypothesis on a basic level: could the essence of my existence be explained in One Sobering Graph, or OSG, now the recognized nomenclature? Read more »

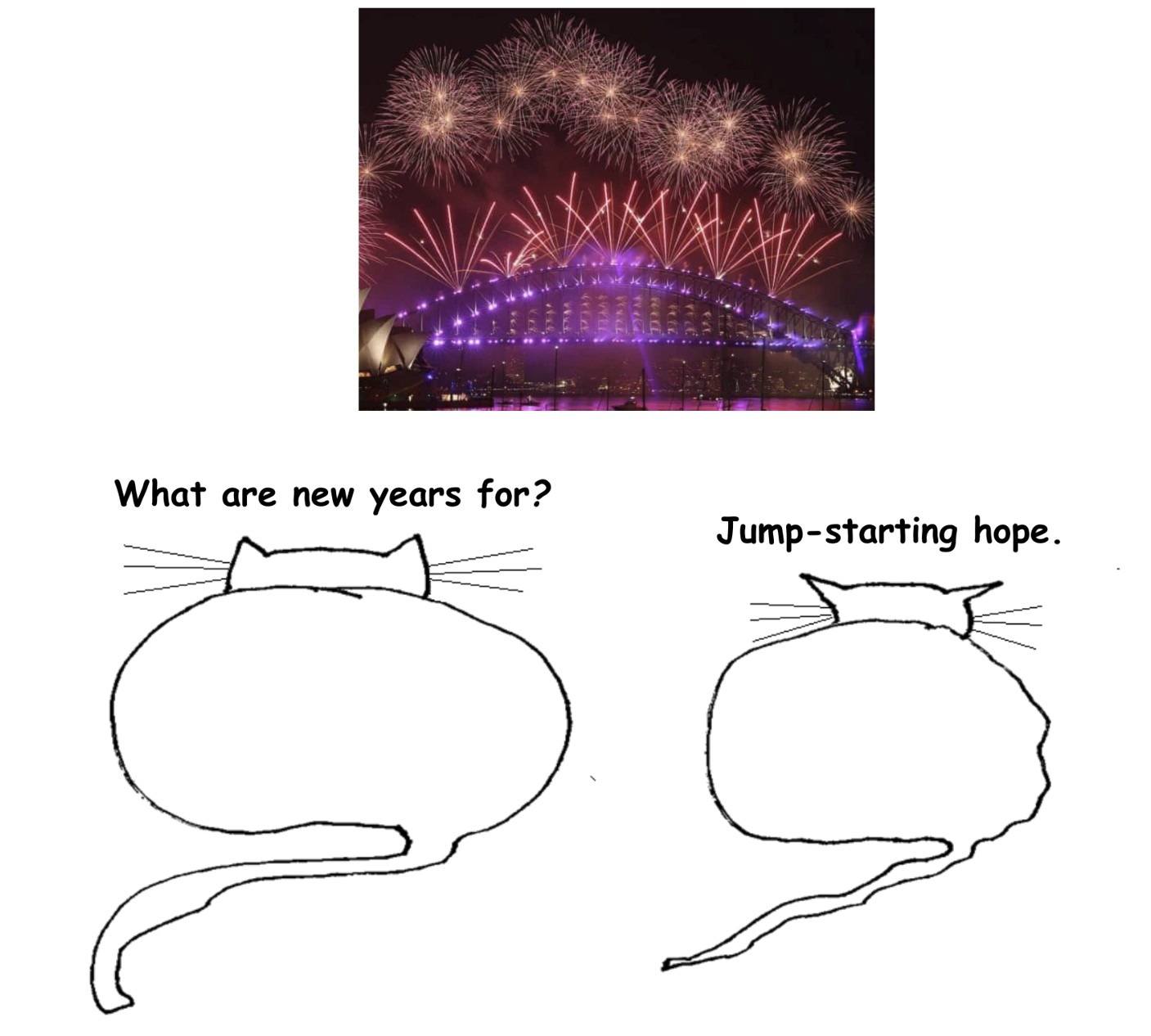

In October of 2014, a bunch of young men and women did their university proud. A couple of engineers, two finance graduates, a biology major, some finishing accounting and business degrees, and a clutch from the school of humanities and social sciences; Muslims mostly, two Christians, a lone Hindu, one Buddhist wannabe, and two oblivious to religion though aware of its place in other folks’ lives. They came together from Sahiwal, Karachi, Gilgit, Swat, Peshawar, Gujranwala, one from Quetta (non-Baluchi), and two from Delhi via the University of Texas. Though the majority of students and faculty stayed away, these young men and women with similar features and skin tones, in colorful flowing kurtas, chooridars, skinny jeans, funky T-shirts, and hijabs, got together to celebrate Diwali, a festival that celebrates Ram’s return from exile.

In October of 2014, a bunch of young men and women did their university proud. A couple of engineers, two finance graduates, a biology major, some finishing accounting and business degrees, and a clutch from the school of humanities and social sciences; Muslims mostly, two Christians, a lone Hindu, one Buddhist wannabe, and two oblivious to religion though aware of its place in other folks’ lives. They came together from Sahiwal, Karachi, Gilgit, Swat, Peshawar, Gujranwala, one from Quetta (non-Baluchi), and two from Delhi via the University of Texas. Though the majority of students and faculty stayed away, these young men and women with similar features and skin tones, in colorful flowing kurtas, chooridars, skinny jeans, funky T-shirts, and hijabs, got together to celebrate Diwali, a festival that celebrates Ram’s return from exile.

Discussions of the factors that go into wine production tend to circulate around two poles. In recent years, the focus has been on grapes and their growing conditions—weather, climate, and soil—as the main inputs to wine quality. The reigning ideology of artisanal wine production has winemakers copping to only a modest role as caretaker of the grapes, making sure they don’t do anything in the winery to screw up what nature has worked so hard to achieve. To a degree, this is a misleading ideology. After all, those healthy, vibrant grapes with distinctive flavors and aromas have to be grown. A “hands off” approach in the winey just transfers the action to the vineyard where care must be taken to preserve vineyard conditions, adjust to changes in weather, plant and prune effectively and strategically, adjust the canopy and trellising methods when necessary, watch for disease, and pick at the right time.

Discussions of the factors that go into wine production tend to circulate around two poles. In recent years, the focus has been on grapes and their growing conditions—weather, climate, and soil—as the main inputs to wine quality. The reigning ideology of artisanal wine production has winemakers copping to only a modest role as caretaker of the grapes, making sure they don’t do anything in the winery to screw up what nature has worked so hard to achieve. To a degree, this is a misleading ideology. After all, those healthy, vibrant grapes with distinctive flavors and aromas have to be grown. A “hands off” approach in the winey just transfers the action to the vineyard where care must be taken to preserve vineyard conditions, adjust to changes in weather, plant and prune effectively and strategically, adjust the canopy and trellising methods when necessary, watch for disease, and pick at the right time.

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend  by Leanne Ogasawara

by Leanne Ogasawara

My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago.

My wife and I took a peek into the interior of Papua New Guinea twenty years ago.