by Shawn Crawford

In the 70s our church caught bus fever as an effort to bring in the sheaves with greater volume (we pass the salvation savings on to you!). We began deploying a fleet of ancient school buses, painted Baptist blue, out into the neighborhoods of town to bring anyone that so wished to church. Heathen parents gleefully signed up their kids so they could read the paper and drink coffee in peace. Today such an effort would be like inviting people to sue you and then providing a free ride to the courthouse. Come for the mass transit; stay for the litigation.

In the 70s our church caught bus fever as an effort to bring in the sheaves with greater volume (we pass the salvation savings on to you!). We began deploying a fleet of ancient school buses, painted Baptist blue, out into the neighborhoods of town to bring anyone that so wished to church. Heathen parents gleefully signed up their kids so they could read the paper and drink coffee in peace. Today such an effort would be like inviting people to sue you and then providing a free ride to the courthouse. Come for the mass transit; stay for the litigation.

A man named Ed kept our Bad News Buses rolling. Ed wore blue coveralls, and I never remember seeing him without a scab on his bald head. Standing on the bumper, he would disappear into the bowels of an angry engine until he emerged grease-covered and muttering to himself. Hopefully Ed now rides in comfort on a bus powered by an inexhaustible supply of love, and his battered dome is smooth and content, bathed every morning in heavenly sunlight.

My uncle helped to make sure the buses had gas and were ready for their Sunday duties. He and I already had a history with vehicles. Indeed we did. My father worked as a Frito-Lay delivery man, stocking the shelves of grocery stores, jockeying for space with Guy’s potato chips and other regional brands. Frito-Lay was just emerging as the dominant player; the introduction of Nacho Cheese Doritos in 1972 would cause their popularity to skyrocket.

Both my uncle and father wanted more, though, and what they especially wanted was to own their own business and work on their own terms. Read more »

When the father of your child is in jail, pray even if you don’t believe in God. Pray even though in your head of heads you know it won’t do shit. Stop staring at the walls, at the clock, at the phone. At your baby, now eight, sleeping next to you, his sneakers, caked with mud, still tied to his feet. Pray because it will distract you from what’s coming, from a conversation millions of mothers have already had with their sons. You are not different, not an exception to some rule. Start praying instead of feeling sorry for yourself. Buck the fuck up because he will need you.

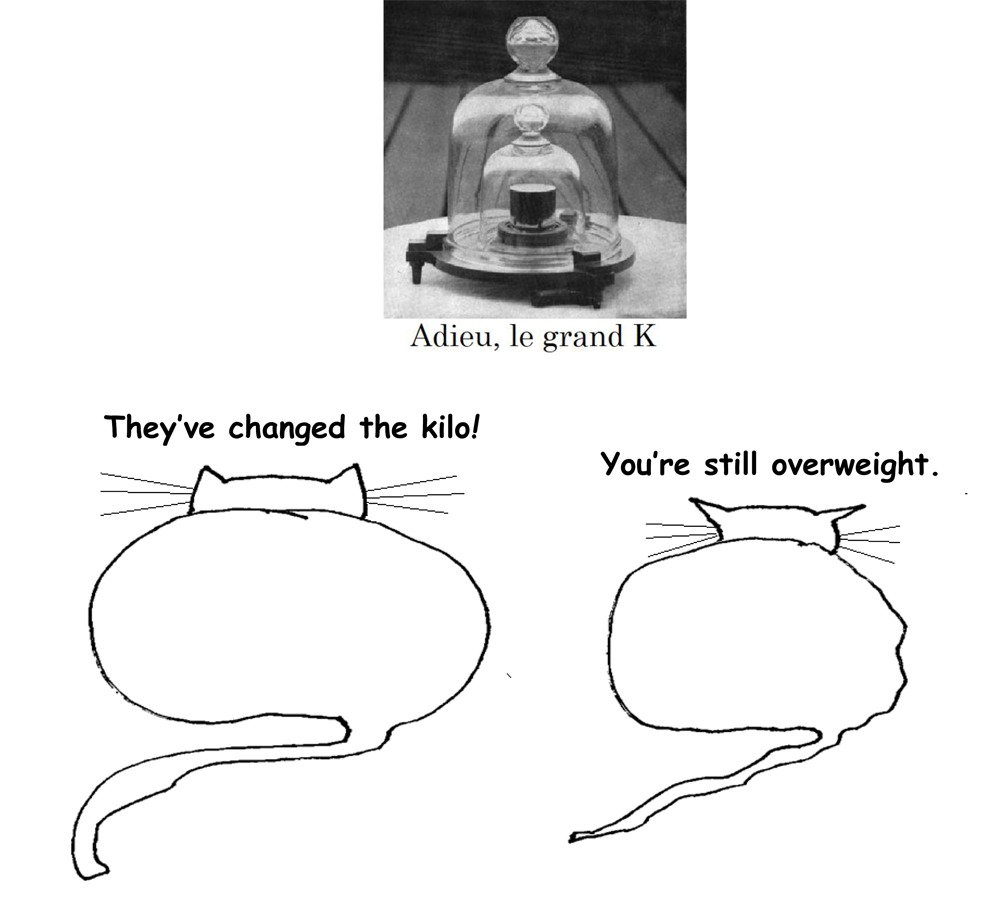

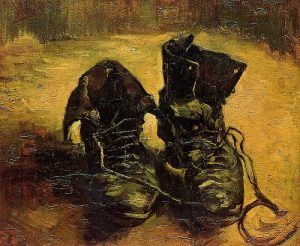

When the father of your child is in jail, pray even if you don’t believe in God. Pray even though in your head of heads you know it won’t do shit. Stop staring at the walls, at the clock, at the phone. At your baby, now eight, sleeping next to you, his sneakers, caked with mud, still tied to his feet. Pray because it will distract you from what’s coming, from a conversation millions of mothers have already had with their sons. You are not different, not an exception to some rule. Start praying instead of feeling sorry for yourself. Buck the fuck up because he will need you. Despite the continued influence of formalism in the 20th Century there were currents of dissent that took an opposing position. Thinkers as diverse as Heidegger, Whitehead and Deleuze were arguing that genuine aesthetic appreciation is not about form but the unraveling of form. Despite their considerable differences, each was arguing that the most important kinds of aesthetic experiences are those in which the dominant foreground and design elements of a work are haunted by a background of contrasting effects that provide depth. It’s the conflict between foreground and background, surface and depth, between what is known and what is mysterious that give art its allure. The uncanny is the key to art worthy of the name. For example, for Heidegger in his famous study of Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes, it’s the seemingly insignificant brushstrokes in the background of the painting that allow amorphous figures to emerge and begin to take to shape as we view it. The background figures preserve ambiguity and allow the concealing and unconcealing of multiple interpretations to take place, which Heidegger argues, are at the heart of a work of art.

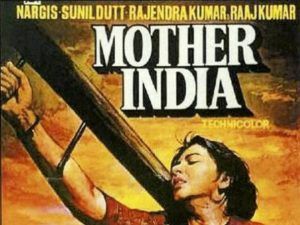

Despite the continued influence of formalism in the 20th Century there were currents of dissent that took an opposing position. Thinkers as diverse as Heidegger, Whitehead and Deleuze were arguing that genuine aesthetic appreciation is not about form but the unraveling of form. Despite their considerable differences, each was arguing that the most important kinds of aesthetic experiences are those in which the dominant foreground and design elements of a work are haunted by a background of contrasting effects that provide depth. It’s the conflict between foreground and background, surface and depth, between what is known and what is mysterious that give art its allure. The uncanny is the key to art worthy of the name. For example, for Heidegger in his famous study of Van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes, it’s the seemingly insignificant brushstrokes in the background of the painting that allow amorphous figures to emerge and begin to take to shape as we view it. The background figures preserve ambiguity and allow the concealing and unconcealing of multiple interpretations to take place, which Heidegger argues, are at the heart of a work of art.  Actors come to each role in a new film bearing the stamp of their old ones so they are richer and more interesting in the new incarnation—the whole more than the sum of the parts. Just last week one saw Nargis as the innocent and naive mountain girl pining away for the love of the ‘shehri babu’, and today she is the femme fatale, all hell and brimstone, plotting the downfall of her rival. Or, as Mother India, upholding principles of honesty and justice, shooting her favorite son dead for raping a village girl.

Actors come to each role in a new film bearing the stamp of their old ones so they are richer and more interesting in the new incarnation—the whole more than the sum of the parts. Just last week one saw Nargis as the innocent and naive mountain girl pining away for the love of the ‘shehri babu’, and today she is the femme fatale, all hell and brimstone, plotting the downfall of her rival. Or, as Mother India, upholding principles of honesty and justice, shooting her favorite son dead for raping a village girl.

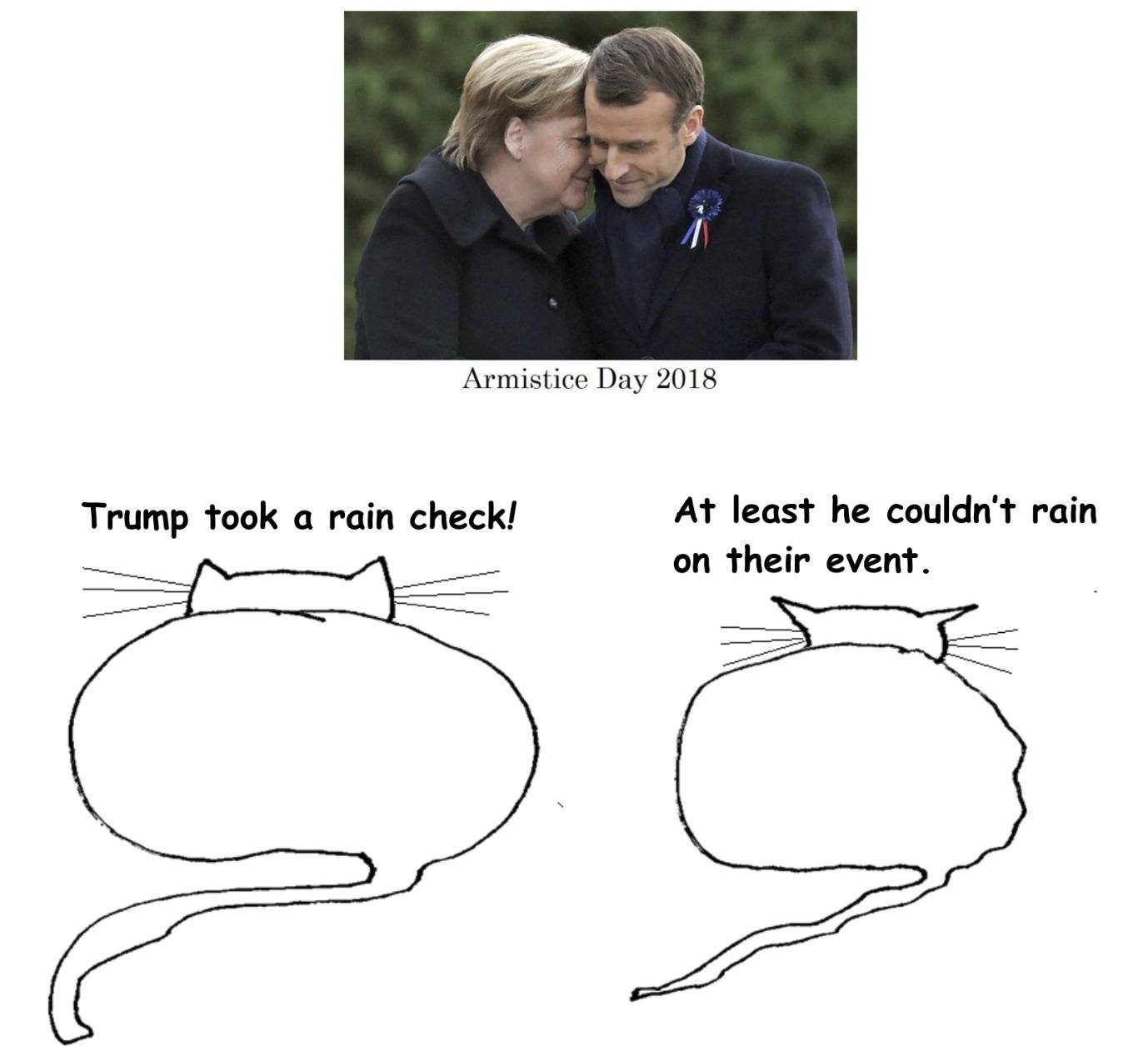

Donald Trump is not a fascist. He’s far too stupid to be a fascist, or to coherently advocate for any complex national political doctrine, evil or otherwise. He is, however, a would-be tin pot dictator. And his largely failed but still very dangerous attempts to establish himself as a right wing autocrat need to be countered, not just by opposition politicians and the press, but also by responsible citizens.

Donald Trump is not a fascist. He’s far too stupid to be a fascist, or to coherently advocate for any complex national political doctrine, evil or otherwise. He is, however, a would-be tin pot dictator. And his largely failed but still very dangerous attempts to establish himself as a right wing autocrat need to be countered, not just by opposition politicians and the press, but also by responsible citizens. This past Sunday, November 11, marked the Centennial of Armistice Day, the European commemoration of the agreement to end World War I. Representatives from more than 60 countries attended carefully choreographed ceremonies to honor the sacrifice of those who fought.

This past Sunday, November 11, marked the Centennial of Armistice Day, the European commemoration of the agreement to end World War I. Representatives from more than 60 countries attended carefully choreographed ceremonies to honor the sacrifice of those who fought.

In a recent study, data scientists based in Japan found that classical music over the past several centuries has followed laws of evolution. How can non-living cultural expression adhere to these rules?

In a recent study, data scientists based in Japan found that classical music over the past several centuries has followed laws of evolution. How can non-living cultural expression adhere to these rules?

The crocodiles know. They form pincers on either side of the crossing point. Richard says they feel the vibration of all those hooves along the riverbank above them.

The crocodiles know. They form pincers on either side of the crossing point. Richard says they feel the vibration of all those hooves along the riverbank above them.

By chance, I chose as holiday reading (awaiting my attention since student days) The Epic of Gilgamesh, a Penguin Classics bestseller, part of the great library of Ashur-bani-pal that was buried in the wreckage of Nineveh when that city was sacked by the Babylonians and their allies in 612 BCE. Gilgamesh is a surprisingly modern hero. As King, he accomplishes mighty deeds, including gaining access to the timber required for his building plans by overcoming the guardian of the forest. But this victory comes at a cost; his beloved friend Enkidu opens by hand the gate to the forest when he should have smashed his way in with his axe. This seemingly minor lapse, like Moses’ minor lapse in striking the rock when he should have spoken to it, proves fatal. Enkidu dies, and Gilgamesh, unable to accept this fact, sets out in search of the secret of immortality, only to learn that there is no such thing. He does bring back from his journey a youth-restoring herb, but at the last moment even this is stolen from him by a snake when he turns aside to bathe. In due course, he dies, mourned by his subjects and surrounded by a grieving family, but despite his many successes, what remains with us is his deep disappointment. He has not managed to accomplish what he set out to do.

By chance, I chose as holiday reading (awaiting my attention since student days) The Epic of Gilgamesh, a Penguin Classics bestseller, part of the great library of Ashur-bani-pal that was buried in the wreckage of Nineveh when that city was sacked by the Babylonians and their allies in 612 BCE. Gilgamesh is a surprisingly modern hero. As King, he accomplishes mighty deeds, including gaining access to the timber required for his building plans by overcoming the guardian of the forest. But this victory comes at a cost; his beloved friend Enkidu opens by hand the gate to the forest when he should have smashed his way in with his axe. This seemingly minor lapse, like Moses’ minor lapse in striking the rock when he should have spoken to it, proves fatal. Enkidu dies, and Gilgamesh, unable to accept this fact, sets out in search of the secret of immortality, only to learn that there is no such thing. He does bring back from his journey a youth-restoring herb, but at the last moment even this is stolen from him by a snake when he turns aside to bathe. In due course, he dies, mourned by his subjects and surrounded by a grieving family, but despite his many successes, what remains with us is his deep disappointment. He has not managed to accomplish what he set out to do. On his journey, Gilgamesh meets the one man who has achieved immortality, Utnapishtim, survivor of a flood remarkably similar, even in its details, to the Flood in the Bible. Reading of this sent me back to Genesis, and hence to two other books,

On his journey, Gilgamesh meets the one man who has achieved immortality, Utnapishtim, survivor of a flood remarkably similar, even in its details, to the Flood in the Bible. Reading of this sent me back to Genesis, and hence to two other books, Comparing Hebrew with Cuneiform may seem like a suitable gentlemanly occupation for students of ancient literature, but of no practical importance. On the contrary, I maintain that what emerges is of major contemporary relevance.

Comparing Hebrew with Cuneiform may seem like a suitable gentlemanly occupation for students of ancient literature, but of no practical importance. On the contrary, I maintain that what emerges is of major contemporary relevance.