by Richard Passov

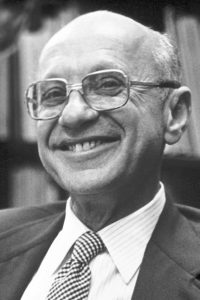

Milton Friedman, in his essay The Methodology of Positive Economics[1], first published in 1953, often reprinted, by arguing against burdening models with the need for realistic assumptions helped lay the foundation for mathematical economics. The virtue of a model, the essay argues, is a function of how much of reality it can ignore and still be predictive:

The reason is simple. A [model] is important if it explains much by little, that is, if it abstracts the common and crucial elements from the mass of complex and detailed circumstances surrounding the phenomena to be explained and permits valid predictions on the basis of them alone.

Agreement on how to allow predictive models into the canon of Economics, Friedman believed, would allow Positive Economics to become “… an Objective science, in precisely the same sense as any of the physical sciences.” What Friedman coveted can be found in a footnote:

The … prestige … of physical scientists … derives … from the success of their predictions … When economics seemed to provide such evidence of its worth, in Great Britain in the first half of the nineteenth century, the prestige … of … economics rivaled the physical sciences.

Friedman appreciated the implications of the subject as the investigator, to a degree. “Of course,” he wrote, “the fact that economics deals with the interrelations of human beings, and that the investigator is himself part of the subject matter being investigated…raises special difficulties…

But he loses the value of his observation to a spate of intellectual showboating:

The interaction between the observer and the process observed … [in] the social sciences … has a more subtle counterpart in the indeterminacy principle … And both have a counterpart in pure logic in Gödel’s theorem, asserting the impossibility of a comprehensive self-contained logic …

The absence of an ability to conduct controlled experiments, according to Friedman, was not a burden holding back progress or unique to the social sciences. “No experiment can be completely controlled,” he wrote and offered astronomers as an example of scientists denied the opportunity of controlled experiments while still enjoying the prestige he coveted.

But though moving economics forward as a positive science – one where predictions are formulated through math and then tested against alternative formulations – he did not want to see mathematics supplant economics. “Economic theory,” he wrote, “must be more than a structure of tautologies … if it is to be something different from disguised mathematics.”

When Friedman penned his article, the simplest mathematical formulations exhausted computational capacity. Read more »

Okay. I’m done. I’m through. I’m hanging up my ruby red slippers, my fuck-me shoes. I’m not going down that yellow brick road no more, no more. I’m giving up internet dating. I may have run a successful antique business in Portobello Road for many years which kept my three children in fish fingers, the three little children I was left with in the middle of Somerset – where I kept chickens, made bread and grew my own veg – when I was 31 and they were all under 6. I may have dragged myself off as a mature student up to the University of East Anglia, after I’d moved us like Ms Whittington to London, to do an MA in Creative Writing with the crème de la crème, whilst juggling child care as the other students hung out talking postmodernism in the bar. I may have written for Time Out, The Independent and The New Statesman as an art critic, published three collections of poetry, one of short stories and three novels but none of this is as anything compared to my failure with internet dating.

Okay. I’m done. I’m through. I’m hanging up my ruby red slippers, my fuck-me shoes. I’m not going down that yellow brick road no more, no more. I’m giving up internet dating. I may have run a successful antique business in Portobello Road for many years which kept my three children in fish fingers, the three little children I was left with in the middle of Somerset – where I kept chickens, made bread and grew my own veg – when I was 31 and they were all under 6. I may have dragged myself off as a mature student up to the University of East Anglia, after I’d moved us like Ms Whittington to London, to do an MA in Creative Writing with the crème de la crème, whilst juggling child care as the other students hung out talking postmodernism in the bar. I may have written for Time Out, The Independent and The New Statesman as an art critic, published three collections of poetry, one of short stories and three novels but none of this is as anything compared to my failure with internet dating.

I know you’ve heard this before. But it’s just too relevant to avoid, so, please, bear with me. It may, or may not, be a garbled version of something Bertrand Russell wrote in Why I am not a Christian, but it has become the equivalent of an urban legend in philosophy. It goes like this. Some famous philosopher or another, maybe Russell, maybe William James, is traveling in some non-Western country, probably India, because of the elephants, and they ask a local informant about their cosmology. The local says, “We believe that the world is a vast sphere resting on the back of four great elephants.”

I know you’ve heard this before. But it’s just too relevant to avoid, so, please, bear with me. It may, or may not, be a garbled version of something Bertrand Russell wrote in Why I am not a Christian, but it has become the equivalent of an urban legend in philosophy. It goes like this. Some famous philosopher or another, maybe Russell, maybe William James, is traveling in some non-Western country, probably India, because of the elephants, and they ask a local informant about their cosmology. The local says, “We believe that the world is a vast sphere resting on the back of four great elephants.”

No one knows if it was really in the state prison, the ruins of which are visible today outside the ancient Agora of Athens, that Socrates was kept during the final days before his execution, so many times has the area been destroyed and reconstructed— walking past it sends a chill down my spine. Ancient Greece is visceral and vivid because it entered my imagination early in life; some of the most cherished tales of my childhood came from the crossovers of Hellenistic history and legend, such as the one in which Sikander (Alexander the Great) is accompanied by the Quranic Saint Khizr, in pursuit of “aab e hayat,” the elixir of immortality, or the one about the elephantry in the battle between Sikander and the Indian king Porus, or of the loss of Sikander’s beloved horse Bucephalus on a riverbank not far from Lahore, the city where I was born. I became familiar with ancient Greece through classical Urdu poetry and lore as well as through my study of English literature in Pakistan, but I would read Greek philosophers in depth many years later, as a student at Reed college; I would subsequently discover Greek influence on scholars in the golden age of Muslim civilization while working on a book on al-Andalus— the overlooked, key contribution of Arabic which served as a link between Greek and Latin, and its later offshoots that came to define the cultural and intellectual history of Europe.

No one knows if it was really in the state prison, the ruins of which are visible today outside the ancient Agora of Athens, that Socrates was kept during the final days before his execution, so many times has the area been destroyed and reconstructed— walking past it sends a chill down my spine. Ancient Greece is visceral and vivid because it entered my imagination early in life; some of the most cherished tales of my childhood came from the crossovers of Hellenistic history and legend, such as the one in which Sikander (Alexander the Great) is accompanied by the Quranic Saint Khizr, in pursuit of “aab e hayat,” the elixir of immortality, or the one about the elephantry in the battle between Sikander and the Indian king Porus, or of the loss of Sikander’s beloved horse Bucephalus on a riverbank not far from Lahore, the city where I was born. I became familiar with ancient Greece through classical Urdu poetry and lore as well as through my study of English literature in Pakistan, but I would read Greek philosophers in depth many years later, as a student at Reed college; I would subsequently discover Greek influence on scholars in the golden age of Muslim civilization while working on a book on al-Andalus— the overlooked, key contribution of Arabic which served as a link between Greek and Latin, and its later offshoots that came to define the cultural and intellectual history of Europe.

1. “…And I, who timidly hate life, fascinatedly fear death.” Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet.

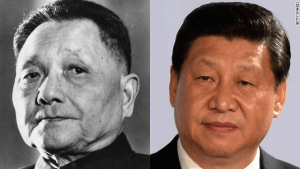

1. “…And I, who timidly hate life, fascinatedly fear death.” Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet. This is the 40th anniversary of the onset of economic ‘reform and opening-up’ (gaige kaifang) in China under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, which eventually led to a dramatic transformation of its economy and global status. It is, however, remarkable that China’s current supreme leader, Xi Jinping, marked the anniversary in a speech in the Great Hall of People in Beijing mainly emphasizing the Party’s pervasive control. It is also remarkable that in recent years this leadership seems to have forsaken Deng’s earlier advice of tao guang yang hui (“keep a low profile”). In the flush of Chinese nationalist glory, Xi explicitly stated in the 19th Party Congress that China has now entered a “new era”, when its model “offers a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence”. Many people both in rich and poor countries seem to be already awe-struck by this model.

This is the 40th anniversary of the onset of economic ‘reform and opening-up’ (gaige kaifang) in China under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, which eventually led to a dramatic transformation of its economy and global status. It is, however, remarkable that China’s current supreme leader, Xi Jinping, marked the anniversary in a speech in the Great Hall of People in Beijing mainly emphasizing the Party’s pervasive control. It is also remarkable that in recent years this leadership seems to have forsaken Deng’s earlier advice of tao guang yang hui (“keep a low profile”). In the flush of Chinese nationalist glory, Xi explicitly stated in the 19th Party Congress that China has now entered a “new era”, when its model “offers a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence”. Many people both in rich and poor countries seem to be already awe-struck by this model.