by Andrea Scrima

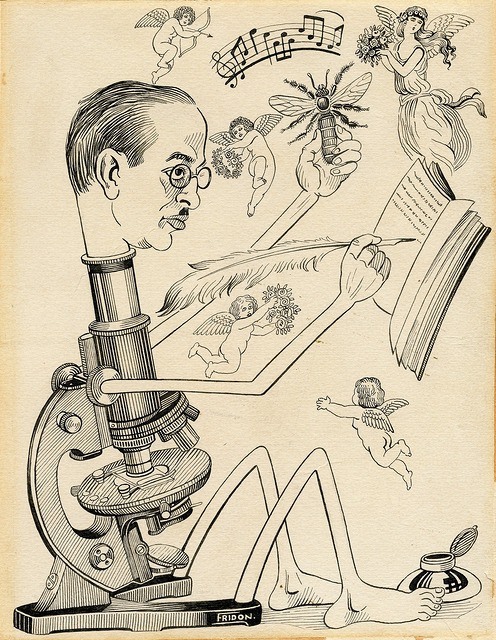

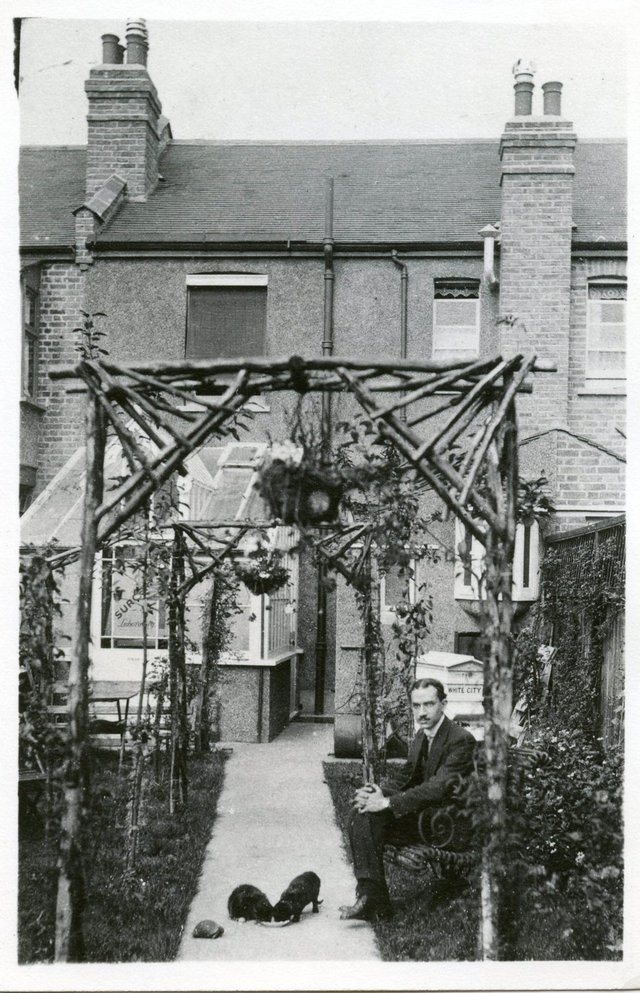

Joy Amina Garnett is an Egyptian American artist and writer living in New York. Her work, which spans creative writing, painting, installation art, and social media-based projects, reflects how past, present, and future narratives can co-exist through ‘the archive’ in its various forms. Her work has been included in exhibitions at New York’s FLAG Art Foundation, MoMA–PS1, the James Gallery, the Milwaukee Art Museum, Museum of Contemporary Craft Portland, Boston University Art Gallery, and the Witte Zaal in Ghent, Belgium, and she has been awarded grants from Anonymous Was a Woman, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Wellcome Trust, and the Chipstone Foundation. Joy’s paintings and writings have appeared, sometimes side-by-side, in an eclectic array of publications, including the Evergreen Review, Ibraaz, edible Brooklyn, C Magazine, Ping Pong, and The Artists’ and Writers’ Cookbook. She has been working on a memoir and several other projects around the life and work of her late grandfather, the Egyptian Romantic poet and bee scientist A.Z. Abushady (1892–1955). Her chapter on Abushady will appear in Cultural Entanglement in the Pre-Independence Arab World: Arts, Thought, and Literature, edited by Anthony Gorman and Sarah Irving, forthcoming from I.B. Tauris. An excerpt from her memoir-in-progress appears in the January 2019 issue of FULL BLEDE, edited by Sacha Baumann.

Andrea Scrima: Joy, you’re the sole steward of the effects of your famous grandfather—the Egyptian Romantic poet and bee scientist Ahmed Zaki Abushady [Abu Shadi]—and have been compiling an archive for several years. First of all, however, I’d like to ask you about your artistic approach to the material and the ways in which history and storytelling interweave in the work. You showed an earlier version of this work-in-progress at Smack Mellon around four years ago, and now, recently, I’ve seen a number of new installments of The Bee Kingdom on Facebook. It makes me think of a kind of novel of layered fragments.

Joy Garnett: I like that description, The Bee Kingdom as a novel of layered fragments, though sometimes it feels like I’m chasing a moving target. It’s been challenging to parlay so many fragments into an artwork or a sustained piece of creative writing, but that is what I’m doing. The source material is not only historically relevant, it’s close and personal, and this affects how I work. And while I want to know the history of what actually happened to my grandfather and my family, and so on, I’m aware of many co-existing unofficial and even secret histories that appear and disappear as I try to make sense of things.

There are other questions, such as what types of media I want to work with. I’ve been a painter all my life, but painting isn’t right for this project. Is The Bee Kingdom mostly writing? Yes and no. I’ve subordinated the visual to writing, but the writing depends heavily on images. Read more »