by Tim Sommers

Old joke. A Calvinist preacher, a firm believer in predestination, is moving his family further west. Seeing him packing his wagon, a neighbor stops to say goodbye. The preacher brings one last item out of his house, a shotgun, and the neighbor asks, “What good is that going to do you? If you get attacked by a bear, and it’s your time to go, that won’t help.” The preacher responds, “What if I get attacked by a bear and it’s the bear’s time to go?”

Predestination is not the same thing as lack of free will (according to Calvinists at least), but, maybe, close enough. On a recent episode of This American Life (episode 662) producer David Kestenbaum made his case against free will like this. “[T]here are only four basic forces in the world – gravity, electromagnetism, and two others, the strong force and the weak force…Our understanding of these forces has been tested and explored again and again…These four forces explain how atoms stick together, how every bit of matter moves, and yes, even the bits of matter that make up us and our brains. We are just collections of atoms. I don’t see how those atoms can truly have any will. When you think you’re deciding, I’m going to wear this shirt today, you can’t really have decided otherwise. We are subject to the forces of nature, not one of them.”

Very convincing all on its own. (I especially like that last line. “We are subject to the forces of nature, not one of them.”) But later on in the show Kestenbaum got some back-up from neuroscientist, and official Genius (Grant Recipient), Robert Sapolsky. Here he is talking about the movement of an eyebrow. “So, let’s simplify it. A muscle did something. Meaning a neuron in your motor cortex commanded your muscle to do that. That neuron fired only because it got inputs from umpteen other neurons milliseconds before. And those neurons only fired because they got inputs milliseconds before and back and back and back. Show me one neuron anywhere in this pathway that, from out of nowhere, decided to say something that activated in ways that are not explained by the laws of the physical universe, and ions, and channels, and all that sort of stuff. Show me one neuron that has some cellular semblance of free will. And there is no such neuron.”

Something has gone wrong here. Did you catch it? I’ll come back to it in a bit, but first I want to talk, not about a reason to believe in free will, but about why you can’t possibly believe that free will (in some form or other) doesn’t exist. Read more »

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

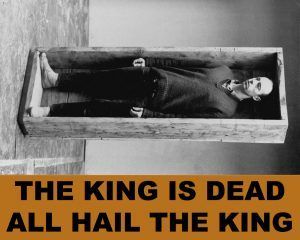

Robert Morris died last month on November 28th at the ripe old age of 87. Very ripe indeed. If he was a fig he’d have been all jammy inside, dribbling the honeyed sugars of maturation. But he’s dead, and I’m glad he’s dead. Let me step back before explaining why – this isn’t an exposition, this is an obituary; I’m grieving; this is diffused ramblings at a podium. I went to Hunter College for undergraduate philosophy and flirted with the art department quite a bit. Morris’ legacy loomed large and hard over the department as he had both attended grad school and taught there. Any course in the art department was bound to encounter his work or his writings. I must have been assigned “Notes on Sculpture” a dozen times. Morris was, and still is, a great artist. His was a scholarly brand of art; neither annoying like Joseph Kosuth, nor dehydrated like Hans Haacke. No, Morris was a genuine student of art and thought. He studied its history, wrote about it emphatically, and contributed to its heritage. It is not difficult to view him as one of the several pillars that contemporary art stands upon today, and feel indebted to his legacy. One of his first well regarded artworks was Box for Standing, which was a handmade wooden box roughly the size of a coffin that fit Morris neatly. How fitting then, that his exit from this life should perhaps be in a box bespoke for his corpse, roughly the same size as his original Box? His expiration has a funny effect on that work, Box for Standing, where his actual death gives the work one last veneer of meaning to stack upon all the other layers. One might have seen similarity between the Box for Standing and funerary vessels before Morris died, but afterward it would be reckless not to see it. The work goes from being a sparse theatrical gesture contained in minimal sculpture, to something like a pragmatic Quaker coffin, verging on bleak humor.

Robert Morris died last month on November 28th at the ripe old age of 87. Very ripe indeed. If he was a fig he’d have been all jammy inside, dribbling the honeyed sugars of maturation. But he’s dead, and I’m glad he’s dead. Let me step back before explaining why – this isn’t an exposition, this is an obituary; I’m grieving; this is diffused ramblings at a podium. I went to Hunter College for undergraduate philosophy and flirted with the art department quite a bit. Morris’ legacy loomed large and hard over the department as he had both attended grad school and taught there. Any course in the art department was bound to encounter his work or his writings. I must have been assigned “Notes on Sculpture” a dozen times. Morris was, and still is, a great artist. His was a scholarly brand of art; neither annoying like Joseph Kosuth, nor dehydrated like Hans Haacke. No, Morris was a genuine student of art and thought. He studied its history, wrote about it emphatically, and contributed to its heritage. It is not difficult to view him as one of the several pillars that contemporary art stands upon today, and feel indebted to his legacy. One of his first well regarded artworks was Box for Standing, which was a handmade wooden box roughly the size of a coffin that fit Morris neatly. How fitting then, that his exit from this life should perhaps be in a box bespoke for his corpse, roughly the same size as his original Box? His expiration has a funny effect on that work, Box for Standing, where his actual death gives the work one last veneer of meaning to stack upon all the other layers. One might have seen similarity between the Box for Standing and funerary vessels before Morris died, but afterward it would be reckless not to see it. The work goes from being a sparse theatrical gesture contained in minimal sculpture, to something like a pragmatic Quaker coffin, verging on bleak humor.  In reviewing “Intimations of Ghalib”, a new translation of selected ghazals of the Urdu poet Ghalib by M. Shahid Alam, let it be said at the outset that translating classical Urdu ghazal into any language – possibly excepting Persian – is an almost impossible task, and translating Ghalib’s ghazals even more so. The use of symbolism, the aphoristic aspect of each couplet, the frequent play on words, and the packing of multiple meanings into a single verse are all too easy to lose in translation. And no Urdu poet used all these devices more pervasively and subtly than Ghalib, and even learned scholars can disagree strongly on the “correct” meaning of particular verses. As such, Alam set himself an impossible task, and the result is, among other things, a demonstration of this.

In reviewing “Intimations of Ghalib”, a new translation of selected ghazals of the Urdu poet Ghalib by M. Shahid Alam, let it be said at the outset that translating classical Urdu ghazal into any language – possibly excepting Persian – is an almost impossible task, and translating Ghalib’s ghazals even more so. The use of symbolism, the aphoristic aspect of each couplet, the frequent play on words, and the packing of multiple meanings into a single verse are all too easy to lose in translation. And no Urdu poet used all these devices more pervasively and subtly than Ghalib, and even learned scholars can disagree strongly on the “correct” meaning of particular verses. As such, Alam set himself an impossible task, and the result is, among other things, a demonstration of this.

In 2018, Earth picked up about 40,000 metric tons of interplanetary material, mostly dust, much of it from comets. Earth lost around 96,250 metric tons of hydrogen and helium, the lightest elements, which escaped to outer space. Roughly 505,000 cubic kilometers of water fell on Earth’s surface as rain, snow, or other types of precipitation. Bristlecone pines, which can live for millennia, each gained perhaps a hundredth of an inch in diameter. Countless mayflies came and went. As of this writing, more than one hundred thirty-six million people were born in 2018, and more than fifty-seven million died.

In 2018, Earth picked up about 40,000 metric tons of interplanetary material, mostly dust, much of it from comets. Earth lost around 96,250 metric tons of hydrogen and helium, the lightest elements, which escaped to outer space. Roughly 505,000 cubic kilometers of water fell on Earth’s surface as rain, snow, or other types of precipitation. Bristlecone pines, which can live for millennia, each gained perhaps a hundredth of an inch in diameter. Countless mayflies came and went. As of this writing, more than one hundred thirty-six million people were born in 2018, and more than fifty-seven million died.

It is simultaneously awkward and exciting to read about your own consciously and responsibly adopted beliefs as something to be anatomized. It is also something atheists are not always much disposed to. On the contrary, perhaps: many forms of atheism present themselves as a consequence of free thought, of emancipation from tradition. The internal logic of their arguments prescribes that while religious beliefs, being non-rational, are in need of cultural or psychological explanation, atheism is really just what you will gravitate towards once you finally start thinking. One question here will be whether this is necessarily the case.

It is simultaneously awkward and exciting to read about your own consciously and responsibly adopted beliefs as something to be anatomized. It is also something atheists are not always much disposed to. On the contrary, perhaps: many forms of atheism present themselves as a consequence of free thought, of emancipation from tradition. The internal logic of their arguments prescribes that while religious beliefs, being non-rational, are in need of cultural or psychological explanation, atheism is really just what you will gravitate towards once you finally start thinking. One question here will be whether this is necessarily the case. Certain phrases choke us with their ubiquity at some point:

Certain phrases choke us with their ubiquity at some point:

As we approach the end of the year, it’s that time again. Not to flip the page to the next month, but to buy a new calendar. (Who am I kidding? It’s probably only me and your grandmother who still uses paper wall calendars…) And also to reflect.

As we approach the end of the year, it’s that time again. Not to flip the page to the next month, but to buy a new calendar. (Who am I kidding? It’s probably only me and your grandmother who still uses paper wall calendars…) And also to reflect.  Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain.

Guinea and Redhead were part of a large food chain. Beyond campus’ freshly-baked sidewalks, a Cowboy Mafia ferried contraband from the south. They landed small prop planes on ranch land outside of town, cut powder with dental anesthetics and broke up the bales. Their wares clumped on our cafeteria trays and glinted in tiny screw-top bottles. The capo, a local big-hat business man,who ran a palatial kicker-dance hall and owned the ranch. That legit business and his crew’s discipline kept them out of jail. Maybe a hat full of cash in the bargain. Philosophers are supposed to ask Big Questions. The Big Questions is the title of a popular introduction to philosophy and of a long-running BBC programme in which people discuss their ethical and religious perspectives. But since we philosophers, following in the footsteps of Socrates, claim to practice critical thinking, it behooves us to ask whether Big Questions are a good idea.

Philosophers are supposed to ask Big Questions. The Big Questions is the title of a popular introduction to philosophy and of a long-running BBC programme in which people discuss their ethical and religious perspectives. But since we philosophers, following in the footsteps of Socrates, claim to practice critical thinking, it behooves us to ask whether Big Questions are a good idea. In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant claimed that in denying knowledge he was “making room for faith.” Inevitably, though, faith in God, the soul and the afterlife has declined dramatically since Kant’s time, especially among intellectuals. There are virtually no articles published in philosophy journals today that treat the existence of God or the immortality of the soul as live issues. Science does not explicitly teach us that there is no God and no heaven, any more than it teaches us that there are no fairies or vampires. But the default attitude of most professional philosophers today is that in such matters the absence of evidence amounts to evidence of absence.

In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Kant claimed that in denying knowledge he was “making room for faith.” Inevitably, though, faith in God, the soul and the afterlife has declined dramatically since Kant’s time, especially among intellectuals. There are virtually no articles published in philosophy journals today that treat the existence of God or the immortality of the soul as live issues. Science does not explicitly teach us that there is no God and no heaven, any more than it teaches us that there are no fairies or vampires. But the default attitude of most professional philosophers today is that in such matters the absence of evidence amounts to evidence of absence.