by Leanne Ogasawara

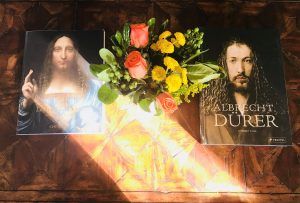

It was mid-summer 2011 when the news broke that a long-lost Leonardo da Vinci painting had been found. Apparently, a New York City art dealer noticed the picture at an estate sale in Louisiana and purchased it for around $10,000. This occurred back in 2005, and the following six years were spent in painstaking work to research and restore the painting. Now in 2011, it was making its public debut in a high profile blockbuster exhibition at the National Gallery in London.

My first thought was: “This is the greatest art historical discovery of my lifetime!”

After all, it has been over a hundred years since the last Leonardo was officially “discovered.” This happened when the Benois Madonna was triumphantly trotted onto the world stage in Saint Petersburg, in 1909. Considered to be one of two very early Madonna paintings that the master himself mentioned working on in his notebooks in 1478, the painting was bought by the Hermitage Museum in 1918 and has remained in that collection ever since. This purchase being much to the chagrin of the American industrialist and art patron Henry Clay Frick, who had plunked down a hefty deposit for the picture– only to lose out in the end, when the Russian czar swooped down to exercise his right to purchase.

Not a prolific artist, it is hard to say which was worse: Leonardo’s chronic procrastination and inability to finish projects or the highly experimental methods in technique and materials that he favored. The result being that not many paintings remain in what is broadly agreed upon by experts to have been done in his hand. Prior to the new 2005 discovery, there were fewer than twenty pictures. So the new discovery was immediately –and not surprisingly– met with a deluge of doubts. First of all, how does one lose something this valuable in the first place? Shouldn’t there by a seamless trail of the work from its conception and initial purchase by a king or duke down through history, as it changes hands for greater and greater sums of money? Leonardo was, after all, legendary even during his own lifetime, with kings and queens clamoring to obtain paintings from the great master. And unlike with my favorite artist, Piero della Francesca, his work never fell out of favor.

Yet despite its tremendous value (or maybe because of it?), his paintings have done their fair share of disappearing tricks. Scandal, skullduggery and intrigue seem to be par for the course when it comes to Leonardo da Vinci.

And this newly discovered Leonardo is no different.

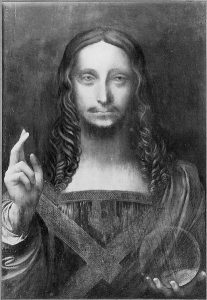

Salvator Mundi is a painting of Christ Triumphant.

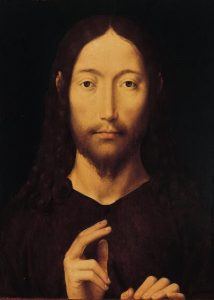

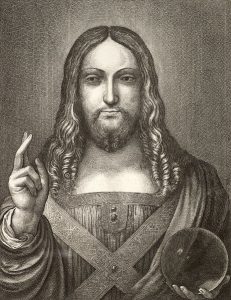

Deriving from Byzantine and Coptic traditions, this style of depicting Christ was made popular by Northern Renaissance painters, such as Jan van Eyck, Hans Memling, and Albrecht Dürer. With his right hand held up in blessing and his left holding an orb, this represents Christ’s promise to save the world.

When I first saw the images of Salvator Mundi online, I found myself spellbound (See Note One). Immediately I was reminded of my favorite Self-Portrait by Dürer (who but Albrecht Dürer would depict themselves as Christ the Savior?) And what about that orb? Wow! It called to mind the glorious exterior shutters of Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delight (See Note Two) –another favorite picture. There was something else that was familiar about the picture that I couldn’t place my finger on. Of course, it was reminiscent of other Leonardo paintings (especially, the Mona Lisa and St. John the Baptist). For whatever reason, Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi came to haunt my thoughts. As if the picture had been burned into my retinas, again and again, I found it floating in front of my eyes before I fell asleep at night: extraordinarily beautiful, Christ stood facing fully front as if in a Byzantine icon against a dark background. With his hands held up in benediction (fingers lit up in light) the luminescence of the chest and forehead dazzles. And what about that rock crystal orb? Some suggested that no one but Leonardo had the skill to paint that orb at that time.

Others begged to differ.

In 2011, there was some talk about the newly discovered Leonardo being a fake (or only very partially done in the painter’s hand). After all, this is the first real problem. How can we define what it means for a painting to be considered an “autograph Leonardo,” when we are talking about work done in an age when masters did not sign their work and of workshops painting practices? (Note Three). People were quick to laugh in the comments section of the Guardian about how the experts had been duped. Others had much to say about the extensive restoration work, wondering if the lady behind the botched Ecce Homo painting in Spain hadn’t had a hand in this Leonardo (Note Four).

The experts, however, were not laughing. They all agreed that the painting in this picture is of the highest quality. Just speaking of materials alone, it uses a great quantity of costly aquamarine and red vermilion. The expense makes it difficult to imagine that this picture was made without a wealthy patron paying the bills ( Note Five). In addition, pigments and binders were analyzed to try and find signature Leonardo techniques. For example, art historian Martin Kemp describes Leonardo’s usual method of painting over his first underdrawing with a light wash of lead (this was not widely shared with other painters) and his laying of a white lead priming directly onto some of his panels without an intervening layer of gesso. His technique of using his hand to model the flesh tones (something seen in the Salvator Mundi) is also idiosyncratic to Leonardo.

In the past hundred years, other “long lost Leonardos” have been found. But those never attained the critical mass in consensus necessary to be awarded with the coveted autograph attribution. This business of attribution is done by experts using a broad spectrum of evidence to make judgement calls. First and foremost is scientific evidence, which is crucial in telling us what a painting is not. If carbon dating concludes that a poplar panel dates from the 17th century then you know the picture in question is NOT a Leonardo. In addition to carbon dating, there is chemical analysis of pigments, and finger printing; as well as x-rays, infrared and UV spectrographs. This kind of science-based evidence goes far in telling you what a painting is not. For example, look at the hands held up in benediction. So expressive, graceful –and more, an x-ray inspection revealed that the painter had a “change of heart” and had altered the position of the thumb– thereby suggesting that this was no copy (Note Six).

But then after you figure out what a painting isn’t, you still need positive proof to tell you what a picture is. And that is done by trying to piece together the provenance of the picture, backed up by stylistic judgements based on connoisseurship.

Ideally, a potential Leonardo would be already known. How? From primary and secondary records. For example, if Leonardo had mentioned having been working on or having completed a Salvator Mundi in his notebooks, than that would create a Holy Grail scenario for a lost Leonardo. Or, if there is 16th century evidence from royal or aristocratic inventories of such a painting, that would also make a strong case.

But, we don’t have that kind of primary early evidence.

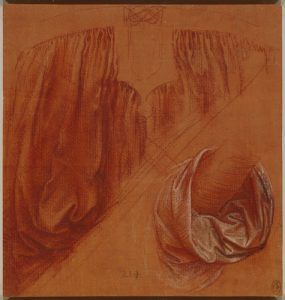

The strongest early evidence we have are the various 16th century copies made by other artists in his workshop or by his followers who were consciously copying what had to be an existing Leonardo. If you have half a dozen copies of the same basic painting, you can assume that there must have been the master work. We also have two preparatory drawings in the Royal Trust Collection (UK) that seem to have been done for this painting.

The lack of a solid early mention of this painting is one of the serious drawbacks for the attribution. But Christie’s, who was handling the auction in 2017, put together a very solid historical trail for this picture from the 17th century onward.

First mentioned as a Leonardo when it entered the royal collection of King Charles I of England, who was the greatest picture collector of his age, it is speculated that French princess Henrietta Maria brought the painting to England when she married the king in 1625. Christie’s suggested that the painting hung in her private chambers at Greenwich, staying behind in England after the queen had to flee in 1644, one step ahead of angry Protestants.

It was around this time when Wenceslaus Hollar made an etching he had made of the painting when it was in the king’s collection. This print is recorded in the inventory of the royal collection, dated 1649. It signed and inscribed with the words, ‘Leonardus da Vinci pinxit’ (Leonardo da Vinci painted it). Although the appearance of the print looks somewhat different from the painting, they are an almost perfect match in terms of dimensions. Around the time the etching was made, Charles I was executed for high treason, and the painting was found included in an inventory of a group of creditors to whom money was owed by the dead king.

It was around this time when Wenceslaus Hollar made an etching he had made of the painting when it was in the king’s collection. This print is recorded in the inventory of the royal collection, dated 1649. It signed and inscribed with the words, ‘Leonardus da Vinci pinxit’ (Leonardo da Vinci painted it). Although the appearance of the print looks somewhat different from the painting, they are an almost perfect match in terms of dimensions. Around the time the etching was made, Charles I was executed for high treason, and the painting was found included in an inventory of a group of creditors to whom money was owed by the dead king.

But this was only a temporary exile, for when Charles II (son of the poor Charles I) was restored to the throne in 1660, the painting was returned to the crown at that time.

Christie’s suggests that the painting probably stayed at Whitehall until the late 18th century.

After this, it went missing for nearly two hundred years.

++

The trail picks up again in 1900, when it entered the Cook Collection. By now, it was no longer considered to be a Leonardo but was recorded as being the work of Leonardo pupil Bernardino Luini. Not the worst thing that can happen, but still this was a monumental fall in status. And worse, still, the face had been extensively over-painted and the panel had been badly damaged. Cook was part of a great art-collecting family and this could have been a soft-landing for the picture. Unfortunately, not fifty years later, it was sold by Cook’s descendants at auction in 1958, where an American buyer fetches it for around $65. It had also by this time been further downgraded as a ‘free copy after Boltraffio’ (another pupil of Leonardo’s).

The painting then crossed the Atlantic and entered an American collection. Still considered the work of one of Leonardo’s “gifted followers,” in America, it got yet another new face (what Leonardo-expert Martin Kemp described as the drug-crazed hippy phase).

The painting then crossed the Atlantic and entered an American collection. Still considered the work of one of Leonardo’s “gifted followers,” in America, it got yet another new face (what Leonardo-expert Martin Kemp described as the drug-crazed hippy phase).

This is how it looked when New York City art dealer Robert Simon noticed the painting up for sale in an auction in Louisiana in 2005.

I would say the rest is history, but the story gets stranger yet!

Enter Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev, stage left.

After being bought out of his business ventures by the Kremlin, Rybolovlev relocated to Monaco in 2010 and immediately bought a soccer team and an almost 10% stake in the Bank of Cyprus. He also bought about two billion dollars worth of art from Swiss art dealer Yves Bouvier, who is also a piece of work, by the way. Bouvier was found to be pocketing commissions from both the buyer and the seller on wildly inflated art. This was how the Salvator Mundi came into Rybolovlev’s collection in 2013, for which he paid some $120 million (it was valued at $80 million). Rybolovlev is suing Sotheby’s for the sale, claiming they were aware he was being ripped off by Bouvier.

And did I mention that Rybolovlev is also being investigated by Special Counsel Robert Mueller (did you see that coming?) for possibly over-paying Donald Trump by $54 million for the $95 million purchase of Donald Trump’s home in Palm Beach in 2006 Trump had bought four years earlier for $41 million. The real estate markup is impossible to explain.

You can’t make this stuff up.

So, how does a Russian oligarch, Donald Trump and a painting by Leonardo da Vinci come together in this scenario?

Well, the working conspiracy theory is that this is how the Kremlin transfers a $54 million dollar payment to Donald Trump.

But it even gets weirder still.

The masterpiece was put back on the market in November 2017 by Rybolovlev. This time Christie’s was handling the sale (as Rybolovlev remains locked in that legal dispute with Sotheby’s). The painting was still estimated at $80-100 million (just like when Sotheby’s sold it). But within moments of the auction beginning the bidding just took off. Two anonymous bidders —supposedly Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed and Saudi Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman– outbid each other until a record-smashing price of $450 million was achieved.

Conspiracy theorists will tell you that this was a public way to launder money to help pay for Trump’s winning presidential campaign.

It’s true that art is used to launder money. But it’s also true that this was a picture that has undergone analysis by the world’s leading experts in the art world.

So what, you say?

So what, you say?

Well, I guess I am not quite ready to live in the post-truth age of conspiracy theories.

Since 2011, when I first learned of the painting, down to today (when conspiracy theorists as we speak claim the picture is MIA) scandal and skullduggery have dogged our beautiful Leonardo. On the one side are the experts, who have come to an astounding consensus that this painting is an autograph Leonardo da Vinci. Their judgements are based on scientific evidence, historical and textual detective work, and good old-fashion connoisseurship (Note Seven). This is not to say there are not dissenters (Note Eight). But it is astonishing that the experts who actually examined Salvator Mundi outside its frame in London 2011, when it was set alongside other notable Leonardo work, such as Virgin of the Rocks, believe this picture to be a Leonardo.

While on the other side, we have journalists and critics who not only have never seen the picture in person, but usually begin their stories with sentences like: “I am no expert on old masters paintings, but…”

Of course, we are all entitled to our opinions. But how did we come to live in a day when the opinions of those who are not experts can stand head and shoulders alongside science-informed and specialist pieces? Are all opinions and judgements really equal? This brouhaha over the Leonardo has captured for me the way being online has become so filled with noise. Can we talk about how the Internet killed journalism? A conservative estimate has the average American spending around two hours a day just on social media, where viral videos and articles which generate anger and anxiety seem to be the name of the game. No wonder people are not reading as many books any more (Note Nine)! In this case the relevant people feel it is authentic.

But the price, you say? $450,000,000?

Well, I will remind you that a Basquiat recently sold for $110,000,000 (painted in acrylic and oilstick on canvas)!

Since the beginning of time, the super wealthy have over-paid for art (Note Ten). But what else is money for but for buying art? And this is an authenticated Leonardo da Vinci (who, I remind you, painted the most famous paintings in European history). It doesn’t mean you have to like it. It doesn’t even mean it’s the real McCoy… since let’s face it, the experts have been fooled before! But for now, it is as close as we have had “officially” in a hundred years. It was purchased to become the crown jewel of the newly opened Abu Dhabi Louvre Museum–and you know what? I think they got a deal!

My 2016 3QD post on Leonardo: Eyes Swimming with Tears

Cabinets Of Wonder: The Shroud Of Turin & The Museum Of Jurassic Technology

++

Highly Recommended: Living with Leonardo: Fifty Years of Sanity and Insanity in the Art World and Beyond, by Martin Kemp

The Eye: An Insider’s Memoir of Masterpieces, Money, and the Magnetism of Art

Sensible Debunking of the Conspiracy Theory

The Italian Art Supply Shop That Keeps Renaissance Painting Techniques Alive

Christie’s Salvator Mundi Timeline

If you are interested in the painting, the Christie’s Special Publication Salvator Mundi is filled with details and gorgeous closeup images.