by Thomas O’Dwyer

French President Emmanuel Macron has set a very large cat among the pigeons of global antiquities trading and curating. The cat – catalogue – is a report he commissioned in March 2018 and it’s named The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics. It identifies tens of thousands of cultural artifacts looted from Africa in French colonial days that could be repatriated. France’s national syndicate of antique dealers has already howled in protest at the report. In a letter to the culture minister, the Syndicat National des Antiquaires wrote: “The risks of extensions to other geographical areas and periods of history do not seem to have been anticipated.” In a separate statement, the syndicate expressed concern that the proposed repatriations would cover objects from the Americas, Asia, the Mediterranean and European countries.

A debate on Western theft from foreign cultures has been around since the nineteenth century. Only now is it gathering real momentum. It is a controversy which rumbles on in specialist magazines and art sections of various media. It erupts at times into open public rows over the most notorious cases – the theft of the Greek Parthenon Marbles by Britain’s Lord Eglin, for instance. There have been vocal demands from Greece, Egypt, Italy, Thailand and China for the return of treasures stolen by colonial marauders. Moral arguments abound over the sale of art pieces that Hitler’s Nazis plundered from European Jews. Such treasures now are often restored to surviving Jewish family members and their descendants. The moral case is that when buyers pay for art objects in good faith, it does not erase the original crime that makes such transactions possible. It is now being argued that this could apply to the millions of stolen artifacts laid out in the dusty cabinets of the world’s great museums.

Theft may indeed be theft, but the topic of restitution is complex, global, emotional and legalistic. Governments and museums usually declare that their precious exhibits came to them in line with laws in place at the time of their removal. This was often done with the consent of regimes eager to profit from their local heritage. It’s an argument that can be self-serving because even when the theft was taking place, there often were voices that condemned it. The poet Lord Byron accused the 7th Earl of Elgin of vandalism and looting for stripping the Parthenon of its sculptures. Parliament exonerated Elgin, who then conveniently sold the Marbles to the government for the British Museum. The case of the Elgin Marbles followed a common pattern of the time. Elgin claimed that Ottoman officials in Athens had granted him a permit. A Turkish military occupier selling off Greek treasures appalled Byron and other philhellenes. It was similar to the outrage in 1974 after the Turkish army invaded Cyprus and the new regime ignored the wholesale theft and sale of Greek Cypriot treasures from the occupied north.

A late nineteenth-century case less well known than the Elgin Marbles, but more scandalous in its scope, also victimised Cyprus. Luigi Palma de Cesnola was the U.S. consul there and used his consular office to strip Cyprus of a staggering 35,000 items of antiquity. This serial looter sold his collection to the new Metropolitan Museum of New York. He was then appointed its director, a post he held until his death in 1904. Cyprus is one of the oldest Greek civilisations in the eastern Mediterranean. It had links to every empire that passed through it – Phoenician, Egyptian, Assyrian, Greek, Hittite, Persian, Roman, Arab, Crusader, Venetian, Turkish and British. But it is a small island, 9,200 square kilometers, and Cesnola’s plundering robbed it of an astonishing heritage of national treasures. His random looting horrified British and other archaeologists. It retarded scientific appreciation of the country’s enormous historical importance for decades.

The New York Met has suffered many blows to its reputation since the end of the last century. A series of allegations and lawsuits have accused it of being an institutional buyer of stolen antiquities. The governments of Italy and Turkey won lawsuits for the repatriation of artifacts worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The Cyprus government insists that Cesnola looted the island for personal gain, but it has not yet shown any inclination to agitate for repatriation. As for the Met, its own documentation, titled The Cesnola Collection, casts a rosy glow over the true story of Cesnola’s predations in Cyprus. It seems an odd attitude for an institution dedicated to disseminating historical facts:

“Cesnola was appointed American consul in Cyprus in 1865. During the next few years, he amassed an unrivaled collection of Cypriot antiquities through extensive excavations and by purchase. The whole enterprise was funded from his own resources. At the time, a number of antiquarians from various European countries were beginning to collect Cypriot antiquities, but they were soon outmatched by Cesnola, who came to dominate the scene in Cyprus.”

Dominate and amass, he did indeed – and “excavation” and “antiquarians” are euphemisms for vandalism. He was the most ruthless of the amateur gentlemen diggers who, in the late 19th century, plundered the abundant antiquities of Cyprus.

Cesnola was born near Turin, Italy in 1832. His family was ancient, but in decline, and Luigi studied for a military career. He served in Austria in 1848 and also in Crimea. In 1860 he emigrated to New York and founded a training school for army officers. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he joined the Fourth Cavalry Regiment of New York with the rank of colonel. He was wounded and taken prisoner at the Battle of Aldie, Virginia. Freed in 1864, he left the army and abandoned his Italian titles. Abraham Lincoln appointed him U.S. consul to Cyprus and he arrived in 1865. The island was still under the sleepy, but sometimes fierce, rule of the Ottoman Turks. Cesnola’s duties were light and he accepted a request to act also as a consul of Russia. Still having ample leisure, he joined in the hunt for ancient treasures which amused the diplomats and educated traders in Cyprus. Academic interest in archaeology was growing – Heinrich Schliemann of Germany was already winning publicity for his excavations at ancient Troy.

Epigraphists were close to deciphering the Iron Age Cypriote syllabary, but mischievous, albeit sometimes scholarly, tomb robbers like Cesnola undermined the infant science of archaeology. They exploited Ottoman indolence and local peasant greed to line their pockets. Apologists for Cesnola argue that archaeological conscience did not yet exist in his day. But some of Cesnola’s British counterparts in Cyprus were careful and conscientious pioneers of the new science. A banker, R.H. Lang, was a restrained and dedicated amateur and tried to offer Cesnola guidance. The U.S. consul practiced neither restraint, science, nor much regard for truth. He was a bull blundering through the china shop of Cypriot history. Over 11 years, Cesnola acquired the largest and richest collection of Cypriot objects ever accumulated by one person. He left behind no documentation of his extensive raids to benefit archaeology, except for one much-maligned book – Cyprus: Its Ancient Cities, Tombs, and Temples. In the few areas where later scholars could identify places he described, his measurements and topography didn’t add up.

The objects which roused the greatest controversy were in his so-called Treasure of Curium collection. Cesnola described the finding of this superb hoard in his book. Archaeologists failed to find the “treasure chambers of Curium” which he described as being more than 10 metres below a mosaic floor. He said the four-metre-high vaults contained his Greek, Egyptian, Phoenician and Assyrian treasures. They included a gold royal armlet, an agate sceptre with golden eagles, rings, necklaces, amulets, a pendant of gold. There was a crystal vase with gold stopper, ruby and amethyst earrings, and great silver platters and bowls. He added terracotta chariots, pottery, bronze tripods, candelabra and utensils to his list. The Treasure of Curium became the glory of the Cyprus collection at the Met. It also became The Cesnola Scandal, as experts and newspapers began to call the Met director a liar and a looter.

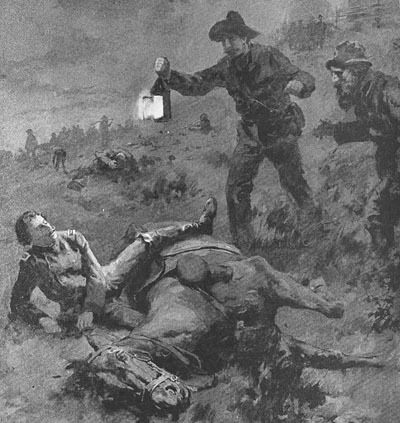

Cesnola was lucky to get his hoard out of Cyprus. By 1870, his acquisitions were becoming substantial. He had just found an untouched Archaic period sanctuary, at Athienou in central Cyprus, containing an immense number of statues. The scale of his excavations had at last alarmed the Ottoman authorities. Cesnola had been removing his loot to a storehouse in the main port of Larnaca. He decided it was time to take a leave of absence to dispose of it. The Grand Vizier of Cyprus denied him permission to move the antiquities – he said Cesnola had a permit for digging, not for moving. The consul decided to shift his 35,000 pieces by force if necessary and asked the U.S. Secretary of the Navy to send a warship. He chartered a vessel at Larnaca, ignoring the arrival of a Turkish man-of-war in the harbour. He parked 360 large cases on the docks ready for loading. Two official Turkish telegrams arrived at Larnaca forbidding the customs officer to issue any movement permit to the U.S. consul. With Levantine cunning, Cesnola immediately swapped hats and applied for the permit in his other role as the Russian consul. The confused customs officer saw no reason to refuse – his orders referred only to a U.S. consul. Cesnola completed the formalities, had his ship loaded in five hours, and sailed for Alexandria and on to London.

A display of the treasures in London aroused great interest and New York city acted to purchase the collection. The government granted Cesnola six months leave to install it in the new Metropolitan Museum. This done, he returned to Cyprus to carry out further searches for the museum but he found little left of any interest. Back in New York he joined the board of the Met and became its director when the museum premises moved from West 14th Street to Central Park. A growing controversy around his morals, methods and mendacity in Cyprus left Cesnola unperturbed. Archaeologists accused him of blatant forgery in restoring some sculptures and bronze art patterns. A sarcastic pamphlet published in 1882 was titled Transformations and Migrations of Certain Statues in the Cesnola Collection. The New York Herald newspaper laid charges against Cesnola that resulted in a long court case and an investigation by a special committee. This exonerated Cesnola, but the controversy rolled on.

The British archaeologist D.G. Hogarth wrote a crushing dismissal of Cesnola’s excavations in his book Devia Cypria. Hogarth investigated many Cesnola sites in Cyprus. He found little that agreed with the published descriptions. The depths at which Cesnola claimed to have found tombs were ridiculous. Instead of reaching 12 metres at Paphos, Hogarth met solid rock after one metre. He failed to find any tombs at 15 meters in ancient Amathus, where a tomb at 5 meters would be extraordinary. No trace of the famed “Curium treasure chambers” was ever found. Geographical areas Cesnola described were wildly inaccurate – many that he mentioned, he could never have visited, Hogarth wrote.

The explanation of the Cesnola mystery was not complicated. The real discoverer of the Met collection was his Turkish dragoman (interpreter and guide, or fixer), Beshbesh. The consul seldom directed or visited dig sites. He followed common practice and contracted the work to local tomb robbers under the supervision of Beshbesh. The Turk did excavate but he also purchased liberally from local bazaars and dealers. He exaggerated details of his digs and finds to justify his expenditure. These “archaeological” details expanded in Cesnola’s fertile imagination and were printed as facts. Collections gathered over long periods he placed in imaginary sites and in those Beshbesh excavated. This explained the bizarre mixture of periods in the Curium treasure. The antiquities were not properly classified until 1914 when Sir John Myres compiled a museum catalogue based on stratigraphic observations. The best comment on his shenanigans came from Cesnola himself: “The excitement of a digger can only be compared with that of a gambler.” A game bird indeed. He gambled with the priceless heritage of a nation for personal gain and, in personal terms, he won handsomely. He received the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1879 and remained in the post he so unjustly deserved until his death.

The silence of Cyprus on the Met’s Cesnola Collection contrasts with the noisy Greek demands for the return of the Elgin Marbles from Britain. Greek Cypriot politicians have been vocal about Turkish looting in the occupied north of their country, but Cesnola’s robbery of antiquities was by far the greatest in the island’s history. There appear to be two explanations. One says that having the collection at such a prestigious location as the New York Met keeps Cyprus’ civilisation high on the world cultural map. That was the view expressed by Glafcos Clerides, a late president of Cyprus, when he inaugurated an exhibition of Cypriot artifacts in New York. The second view is that Cypriots think the Ottoman export permit which Cesnola obtained by subterfuge was probably legal enough to make a battle with the mighty Met too costly to pursue. Dr. Despo Pilides, the curator of antiquities in Cyprus, compared the cases of the Elgin Marbles and the Cesnola Collection, in an interview with the Cyprus Mail.

“In a way they can still be compared,” she said. “They were both exported under the same laws – laws in inverted commas – meaning it was under a law being implemented by a country occupying another country and giving a licence to export items belonging to the occupied country. Both are similar in that way, and the philosophy behind [their repatriation] is also the same. We can’t demand them back because they were exported by the law of the time, so legally we don’t have a good case.”

The reporter asked her if museums might repatriate at least some important items for goodwill, at some point.

“Museums don’t have goodwill,” Pilides said. “Cyprus has on numerous occasions expressed its wish for the return of the Cesnola Collection. Maybe with increased demands from robbed countries, attitudes will eventually change. But not any time soon.”