by Andrea Scrima

Joy Amina Garnett is an Egyptian American artist and writer living in New York. Her work, which spans creative writing, painting, installation art, and social media-based projects, reflects how past, present, and future narratives can co-exist through ‘the archive’ in its various forms. Her work has been included in exhibitions at New York’s FLAG Art Foundation, MoMA–PS1, the James Gallery, the Milwaukee Art Museum, Museum of Contemporary Craft Portland, Boston University Art Gallery, and the Witte Zaal in Ghent, Belgium, and she has been awarded grants from Anonymous Was a Woman, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, Wellcome Trust, and the Chipstone Foundation. Joy’s paintings and writings have appeared, sometimes side-by-side, in an eclectic array of publications, including the Evergreen Review, Ibraaz, edible Brooklyn, C Magazine, Ping Pong, and The Artists’ and Writers’ Cookbook. She has been working on a memoir and several other projects around the life and work of her late grandfather, the Egyptian Romantic poet and bee scientist A.Z. Abushady (1892–1955). Her chapter on Abushady will appear in Cultural Entanglement in the Pre-Independence Arab World: Arts, Thought, and Literature, edited by Anthony Gorman and Sarah Irving, forthcoming from I.B. Tauris. An excerpt from her memoir-in-progress appears in the January 2019 issue of FULL BLEDE, edited by Sacha Baumann.

Andrea Scrima: Joy, you’re the sole steward of the effects of your famous grandfather—the Egyptian Romantic poet and bee scientist Ahmed Zaki Abushady [Abu Shadi]—and have been compiling an archive for several years. First of all, however, I’d like to ask you about your artistic approach to the material and the ways in which history and storytelling interweave in the work. You showed an earlier version of this work-in-progress at Smack Mellon around four years ago, and now, recently, I’ve seen a number of new installments of The Bee Kingdom on Facebook. It makes me think of a kind of novel of layered fragments.

Joy Garnett: I like that description, The Bee Kingdom as a novel of layered fragments, though sometimes it feels like I’m chasing a moving target. It’s been challenging to parlay so many fragments into an artwork or a sustained piece of creative writing, but that is what I’m doing. The source material is not only historically relevant, it’s close and personal, and this affects how I work. And while I want to know the history of what actually happened to my grandfather and my family, and so on, I’m aware of many co-existing unofficial and even secret histories that appear and disappear as I try to make sense of things.

There are other questions, such as what types of media I want to work with. I’ve been a painter all my life, but painting isn’t right for this project. Is The Bee Kingdom mostly writing? Yes and no. I’ve subordinated the visual to writing, but the writing depends heavily on images.

The ongoing difficulty is in choosing how to elevate this material, how to transform it conceptually and formally when it is all very compelling to begin with. I have produced a few multi-media projects, as you mention. The first was part of a traveling show about archives and ephemera organized by the artist Yevgeniy Fiks, and the subsequent work at Smack Mellon drew on Abushady’s beekeeping artifacts. Both projects gave me a reason to explore materials in the archive.

A.S.: In your recent Facebook posts, you combine short descriptive prose with photo sequences—for instance, of your family’s arrival in New York and the price of nylons.

J.G.: I’ve been using Instagram (which simultaneously posts to Facebook) as a sketchbook to play with images and short texts. I jot down a few brief sentences that refer to longer pieces I’ve been working on—it’s very quick, like slam writing—and I post them with one or more images. The connection between the words and images is a little ambiguous. The result oscillates between poetic aphorism and memory.

A.S.: You’re also in the process of writing a book, aren’t you?

J.G.: Yes, and it took me a long time to figure out what I wanted the book to be, if it should include excerpts of letters or diaries, if it should be partly fictionalized, if it should include images, and so on. At first I thought I was putting together missing information to round out the official history of my grandfather. But I’m not interested in academic writing, and I’m not a scholar. I am interested in how vernacular materials reveal minute complexities about people, places, and things. That’s where the archive comes into play. And so the book has developed into a literary memoir, the story of the Egyptian side of my family told through three generations of women. Our voices. Intertwined personal stories.

A.S.: How do the other members of your family feel about your approach to this history?

J.G.: They have been extremely supportive. Some have been instrumental in helping me search for and rescue many of these materials at a moment when they were nearly lost and destroyed. My family has helped me think about the stories, too. We each have a different angle, different information, and so together we’ve tried to piece together some of the puzzles.

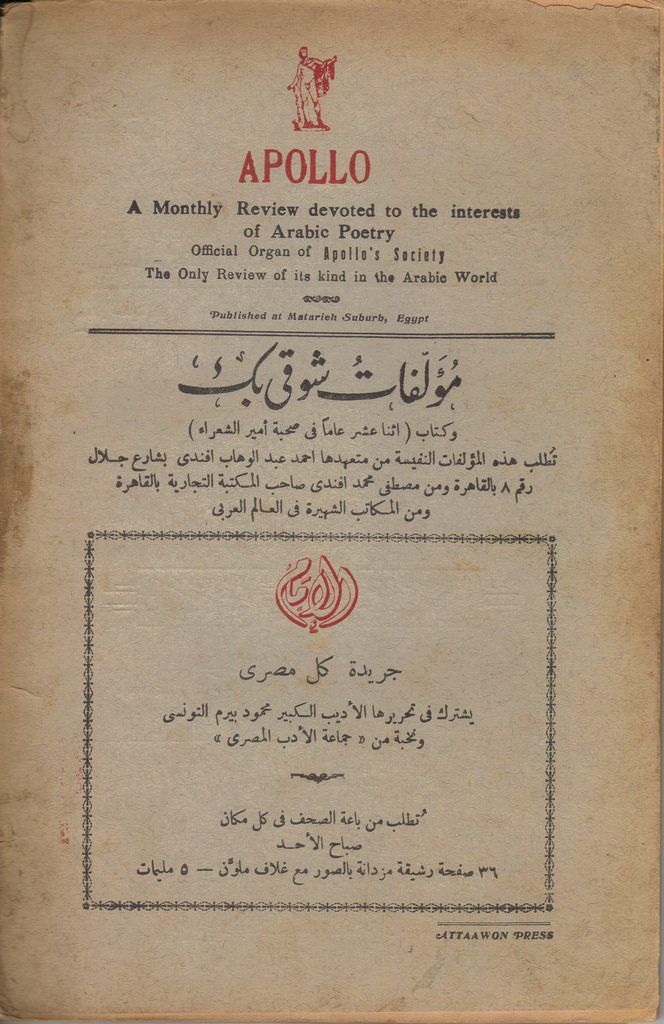

A.S.: Back in Egypt after his decade-long stay in England, Abushady founded the poetry journal Apollo (1932–34), which published experimental poetry from across the Arab world. He translated important Arab poets into English and several of Shakespeare’s tragedies into Arabic. And his influence on Arabic letters continued long after he moved to the United States in 1946. As the only heir with a serious interest in preserving your grandfather’s legacy, you’ve single-handedly turned these holdings into an extensive archive.

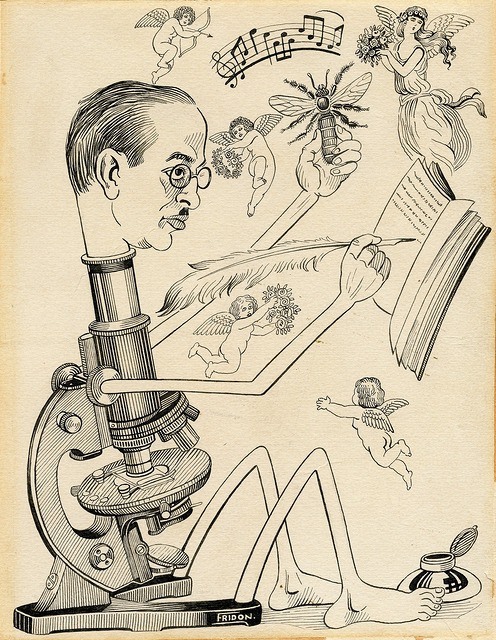

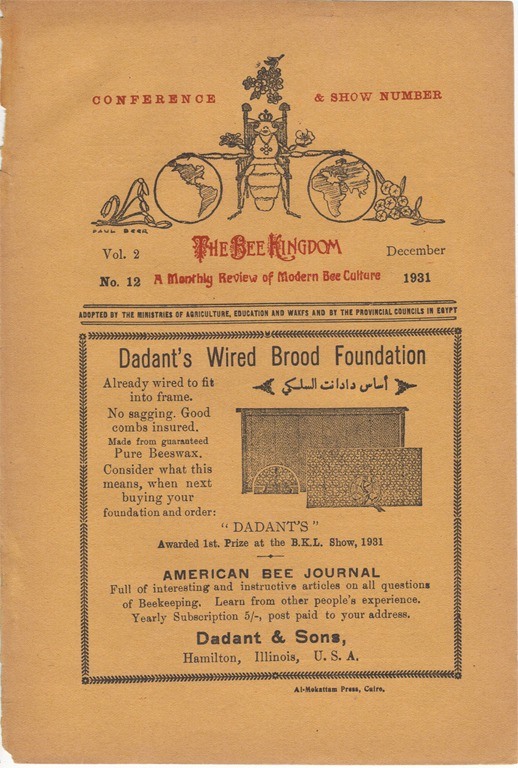

J.G.: Abushady was an influential figure at a time when Arabic poetry was going through a radical shift, and in addition to being a prolific poet and translator, he was an editor and publisher. Apollo allowed him to provide a platform for young writers and experimenters to publish their work alongside luminaries of Arabic poetry. He gave local artists exposure as well—cartoonists, calligraphers, painters, illustrators—Apollo was unique for its copious illustrations.

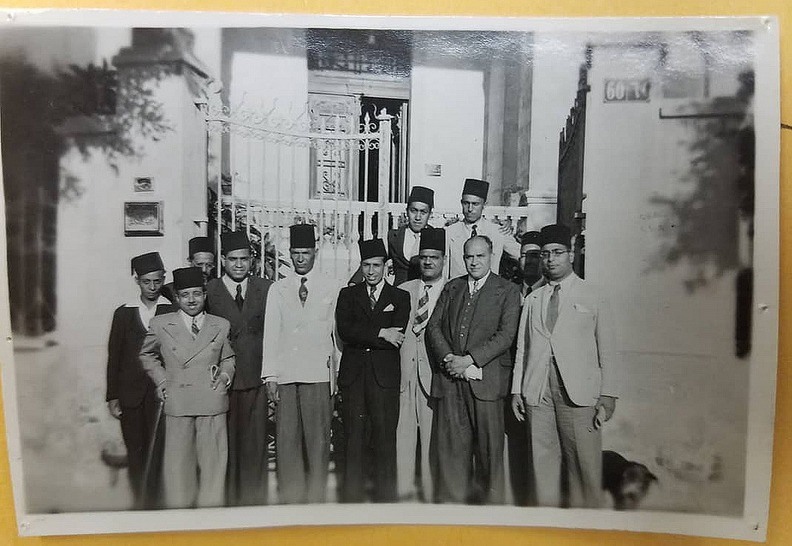

I am, of course, interested in helping to preserve his legacy, and I’ve done my best to learn everything I can about him. While organizing the archive, I’ve had help, not just from family and friends, but from distant acquaintances who appreciate its significance: scholars of modern Arabic poetry, archivists, curators, librarians, historians, and graduate students have visited and examined these documents with me, answered my queries by email, or helped me with on-the-spot translations. I owe many debts of gratitude. As it now stands, the archive consists of forty-one boxes containing ephemera, original artworks, photographs, manuscripts, books, journals, audio recordings, correspondence and other papers pertinent to Abushady’s work, as well as vernacular materials dating from the early half of the twentieth century that reflect the deliciously (to me) mundane aspects of family life in Cairo and Alexandria between the wars.

A.S.: From 1919 to the late 1930s Abushady founded several bee research institutes and scientific journals in England and Egypt, some of which are in existence to this day.

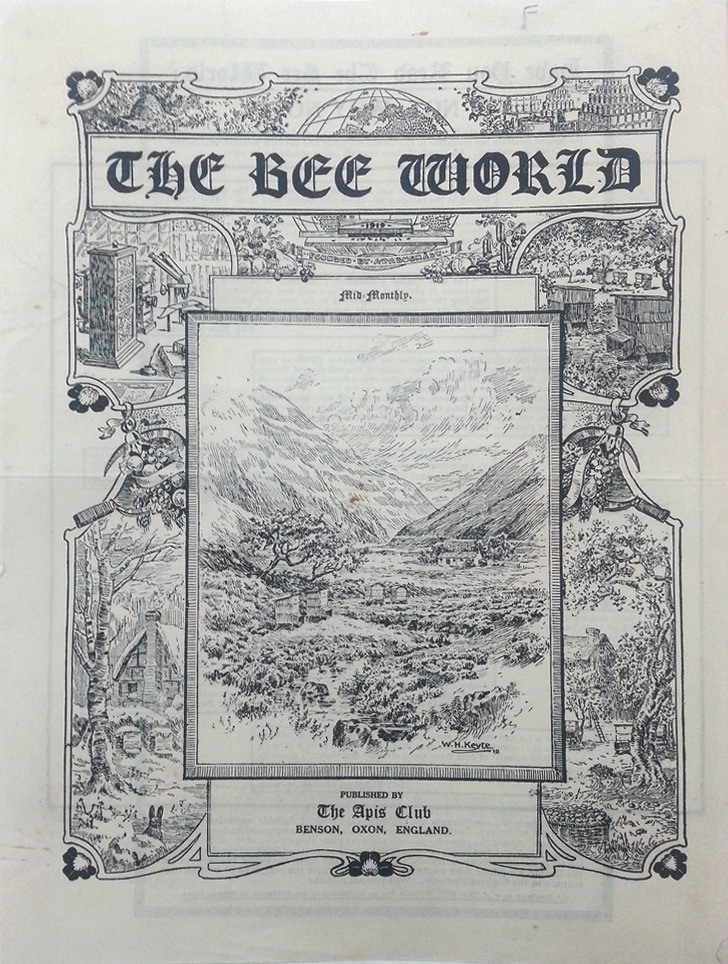

J.G.: It’s really stunning to me that his first journal, Bee World, which he launched in 1919, is still being published. In celebration of its centennial, the publisher, International Bee Research Association, will be putting together a special issue with a few images from the archive.

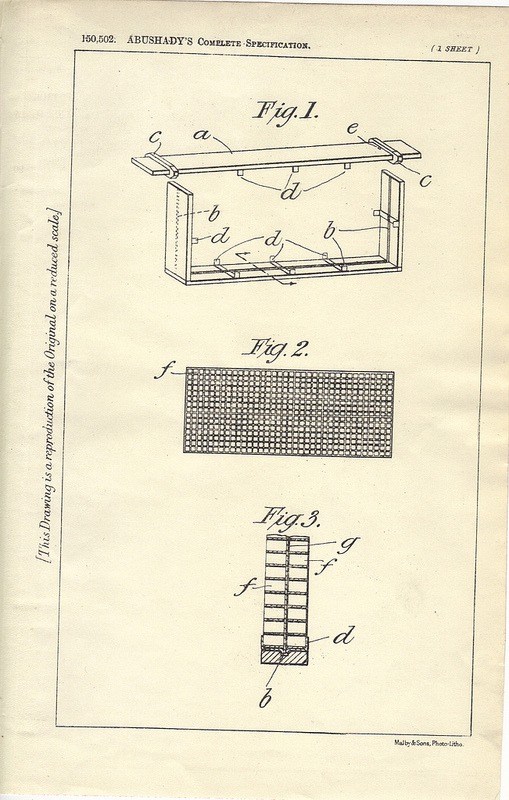

Abushady presented his research through Bee World, and he put his innovative ideas into practice through the Apis Club, the beekeeping co-operative and experimental apiary he founded in Oxfordshire in 1919. That same year, he registered several patents for beehive improvements, including a design for a removable aluminum honeycomb, which he then had fabricated for use in his apiary. He had big plans, such as building a public beekeeping library and a school, but he was called back to Egypt before he could realize them.

He returned to Cairo in 1922, and by 1930 he had launched another bee husbandry group, the Bee Kingdom League, and a bilingual Arabic-English bee journal, The Bee Kingdom, which he edited and published for eight years. He kept a large apiary in the Delta, in Khorshed, and honey sales provided him with a supplementary income. By the mid-thirties, his bee enterprises had attracted attention, and he was invited to establish King Farouk’s royal apiaries.

A.S.: In ancient Egypt, the bee was a symbol of royalty and power; cultures of Asia and the Middle East considered it a sacred insect. In the modern era, the social organization of bees has been anthropomorphized and interpreted (and politicized) in a variety of ways as a model for human society: as the cold, rational, industrial order of the modern world; as a cooperative egalitarian community; as an inescapable repressive social hierarchy in which workers are doomed to a fate of relentless labor. Abushady regarded the social structures of bees as a kind of blueprint for a utopian society founded on economic cooperation. How did the study of bees inspire his visions for a better society?

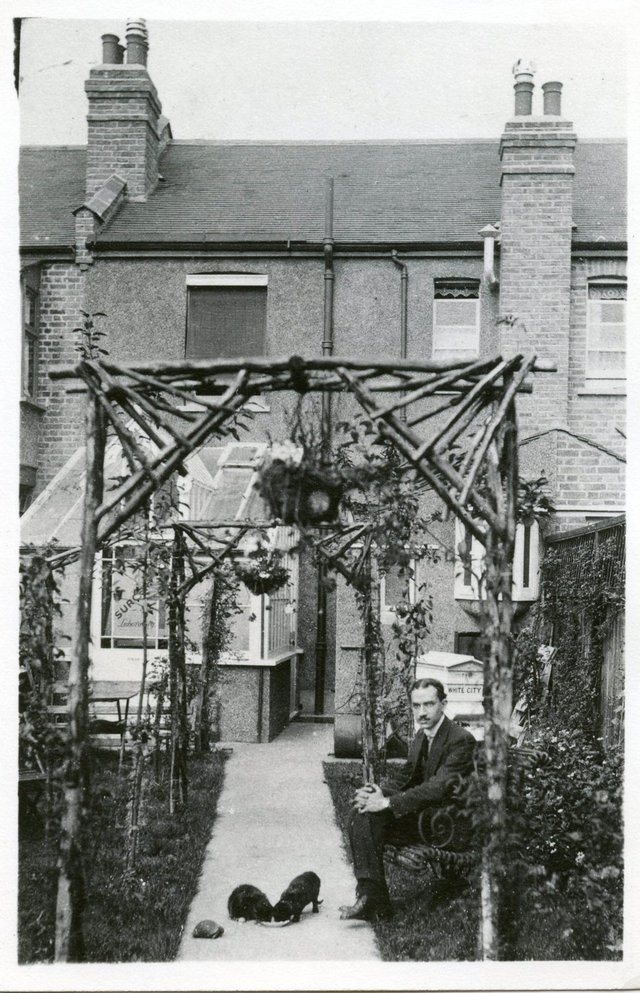

J.G.: I’m not sure what led him to study bees, or exactly when he became interested in them. Several 1917 photographs show him sitting with a beehive in the garden behind his house in Ealing. These photos are the earliest evidence I have of his involvement with beekeeping.

I do think his political awakening may have come first, though, and colored his understanding of “bee culture.” I can date his political activities to a 1913 photograph. He is sitting with the Egyptian-British actor, pan-Africanist, and anti-colonial agitator, Dusé Mohammed Ali. I found the photo only recently, and it prompted me to dig up and revisit an email a friend had sent me years before, with an excerpt from a 1915 British Secret Service file he found while doing research in the Public Records Office in London. It describes Abushady as one of the many “Turks and Egyptians” that frequented Dusé’s home. The police intercepted a letter he sent to his father in Cairo that was “violently anti-English.” They interviewed him, noting his disappointment over the proclamation of the Protectorate of Egypt, and that he felt more positive upon learning that Egypt would have home rule. The police intercepted another letter that Abushady sent to Dusé’s wife, a translation of Arabic verse by Egypt’s poet laureate, Ahmed Shawqi, exhorting Egyptian school children to “cease being slaves” by “sacrificing themselves to restore the ancient glories of Egypt.”

The photo and the Secret Service file contradict the popular image of Abushady as an unapologetic anglophile. Of course, he was an unapologetic anglophile. He was enormously influenced by English modernist poetry, which he used as a springboard for experiments with Arabic free verse. And he married an Englishwoman, Annie Bamford, who became my grandmother. I think I can hold these two contradictory images in my head at once—the violently anti-English young man, and the unapologetic anglophile who fell in love with Annie. People are complicated.

His relationship with Annie may have opened him to a different kind of social and political awareness. She came from a long line of working-class laborers and cotton weavers—her great uncle was the Lancashire poet and labor organizer Samuel Bamford, author of Passages in the Life of a Radical (1840–44). It’s not unreasonable to suggest she may have inspired Abushady to put into practice the principles of the Rochdale Pioneers (the progenitors of today’s co-ops) when he established his first apiary. He was a son of privilege from a class of Egyptian professionals. But Egypt was not yet independent. He was preoccupied with its path to modernization, which he believed should begin with free education, civil marriage, women’s suffrage, and the eradication of poverty. Annie exerted an influence on his grand scheme.

Bee husbandry was his model for carrying out deeply-felt ideals about social reform. Practicing medicine exposed him to poverty in inner cities and rural areas across England and Scotland. He worked through the influenza pandemic, and dealt with cholera outbreaks and children suffering from malnutrition. By launching and editing Bee World, he gave himself a platform, and while he primarily wrote about developments in bee science and husbandry, he also used it as a soapbox. He encouraged knowledge-sharing among beekeepers from different social strata and pushed for agricultural reforms and the standardization of beekeeping practices, demonstrating, in theory and in practice, how farmers could dramatically increase honey yields and, hence, improve their standard of living.

A.S.: Bee research has shown how a small oligarchy of bees comprising no more than 5% of the hive determines when the signal is given to swarm, in other words, when to enact the abrupt mass departure to found a new colony elsewhere. The phenomenon has been known for centuries, but it’s only recently that scientists have identified the “piping” signal certain forager bees give to trigger an exodus after they’ve scouted a location for a new hive. They also, apparently, engage in a kind of dance in which they wiggle their bottoms. I know I’m getting carried away with bees at this point, and that this is no more than speculation, but it really makes me wonder to what extent Abushady’s profound interest in bees mirrored his visions for the political future of Egypt. By the time he returned in 1922, Egypt had attained independence, although British political influence and military presence continued for several decades. How strong were his ties to the royal court, and what led to his emigration to the United States?

J.G.: By the time the war ended, Abushady could not stay in Egypt. During the war, he wrote increasingly scathing opinions against Farouk, who had become a corrupt, morbidly obese kleptomaniac. The atmosphere in Egypt was one of paranoia. Abushady was blacklisted. No one would publish his poetry or political essays, and so he had to self-publish. He feared he would be arrested, taken away at any moment. By 1945, Annie was gravely ill—things looked bleak—and his three rather privileged children, aged 22, 19, and 18, were undoubtedly ill-equipped to deal with life without parents in post-war Egypt. It took a lot of maneuvering, but with the help of a well-connected family friend, Abushady obtained exit visas and paperwork for the five of them to emigrate to the United States. They booked tickets on one of the first transatlantic-bound ships to depart the port of Alexandria at the close of the war. But Annie died in February. They had to bury her, and so they missed their boat and rescheduled their departure.

On April 13, 1946, Abushady and his children left Egypt on the SS Vulcania, stopping in Naples and arriving a few weeks later in New York City. They lived in Manhattan for a while, then moved to a house in Springfield Gardens, Queens. Abushady continued to write and publish poetry and essays for the next decade, and he worked for the newspapers of the Arab expat community in New York. He contributed to local bee husbandry clubs, gave lectures and demonstrations, and became a member of the Bronx Beekeepers Association. He remarried an American woman named Constance Wellman, who became a sort of family villain—the evil stepmother. Constance was a serial divorcee who had once been married to the painter John D. Graham and then to a Saudi businessman before she met my grandfather. He eventually moved to Washington, D.C. to work for the Voice of America, producing literary and cultural content in Arabic and English for their radio program. He suffered a stroke and died at home on April 12, 1955.

A.S.: How aware were you of your grandfather’s legacy growing up? Have you been able to get a sense of what kind of man he was, or did the fascination begin with his wife, your grandmother?

J.G.: Growing up, his ghost was all around me, the stuff of fairy tales, but I didn’t have a real sense of him as a person. My mother and aunt put him on a pedestal—their father, the famous Egyptian poet and doctor. Much literary criticism has been written about his poetry, so I spent years reading and absorbing as much as I could while trying to put together a more intimate and complex picture of him. As an undergraduate, I studied classical and spoken Arabic, and recently I took a series of hands-on beekeeping classes.

As for Annie, I had albums full of photographs and a few anecdotes. Otherwise, I was on my own. But then I made a surprising discovery: I found a cache of correspondence between my grandparents, letters written over a four-year period in which they spent the summer months apart (1931–34). They wrote to each other every day, sometimes twice a day. They wrote in English, in legible handwriting. There are over 200 letters. I went from knowing very little, to having, at my fingertips, both sides of a long-term conversation between husband and wife.

A.S.: You mentioned the word “fiction” as an option for approaching the book. At the same time, the very act of compiling an archive is one of devotion, care—and painstaking accuracy. Yet the dedication one brings to bear in locating material and researching dates and facts might, in a sense, already harbor the seed of that fiction, because there’s a propelling force behind that obsession—it takes a certain type of imagination. We don’t always know what we’re looking for when we look to the past.

J.G.: We don’t always know what we’re looking for, and very often, we find something we didn’t expect, something that opens a whole world we didn’t know existed. A discovery like that can change everything (the Dusé photograph, the letters). We then have to confront our own assumptions as well as the gaps and biases present in historical narratives that we and everyone else had always accepted as accurate.

There was a point when I had to stop working on the archive, when I realized that it could easily become a project without end. There are also tasks I cannot begin to undertake, translations and scholarly work best left to translators and scholars. When it comes to writing this story, I have had to learn to step away from the facts and the problems inherent in trying to be accurate, which are often really questions of viewpoint. To write a story worth reading, the problem shifts away from ascertaining the facts to that of teasing out strands of experience and individual voices. Facts become the enemy. The writing can only rise to the level of art when I let go of my fear of misrepresentation and begin to trust my instincts, my ability to hear and transcribe voices, including my own.

For more information visit The Bee Kingdom.