by John Schwenkler

What is the point of being courteous, kind, and otherwise well-mannered?

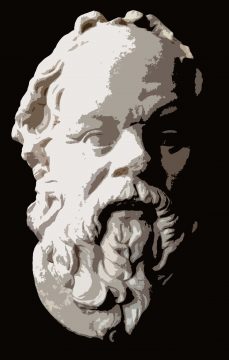

I suspect that most of us are inclined toward an answer that parallels Thrasymachus’ view of justice in the early books of Plato’s Republic. For Thrasymachus, what really matters to us where questions of justice are concerned is all on the side of self-interest. We care about justice in others only to the extent that it brings benefits to us and our friends, and we care about embodying justice in our own lives only to the extent that justice wins us friends, while unjust action carries the risk of punishment and social sanction. The attractiveness of this view comes out in Plato’s famous retelling of the myth of Gyges: given the power to act either justly or unjustly without being detected by others, any of us would choose the life of total injustice. In themselves, the demands of justice are at odds with the desires of naked self-interest, and the only thing that motivates us to respect them is the fear of what will happen to us if we don’t.

An analysis along these lines is even more attractive in connection with the traditional demands of courtesy. Many of us will have the sense that there is — or at least could be — something objectively, universally wrong with stealing, lying, murdering, or imprisoning a person without proper cause. By contrast, no such status accrues to the demand to wear a collared shirt to work or put a napkin on one’s lap while eating: customs like these are contingent, local practices a large part of whose purpose is to mark off the one who observes them as a member of polite society. Meanwhile, even those aspects of good manners whose justification seems more fundamental, such as keeping disparaging thoughts to oneself and refraining from interrupting one’s conversational partners, are all such as to be dispensable in certain situations. What force do they have, then, except as the impositions of an oppressive, socially stratified culture? Read more »

1.

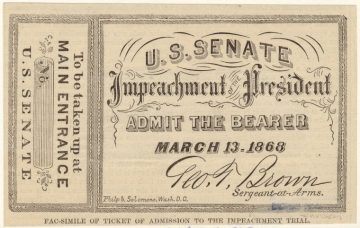

1. I have an awful confession to make. I haven’t made up my mind about whether President Trump should be convicted and removed from office.

I have an awful confession to make. I haven’t made up my mind about whether President Trump should be convicted and removed from office. When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, the poet Nora Gomringer expressed her satisfaction at the recognition thus afforded not only poetry, but in particular songwriting, which she identified as the very wellspring and guarantee of literature, citing in her appraisal such classical forebears as Sappho and Homer. In an article published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gomringer mocked the conventional Western view of letters, a canon founded on prose and the novel, and now challenged by the award to Bob Dylan: “Literature is serious, it is beautiful, it is a vehicle for the noble and the grand; poetry is for what is light, for the aesthetically beautiful, it can be hermetic or tender, it can tell its story in a ballad and, if especially well made, can invite composers to set it to music…”. But “such categories”, she went on to suggest, “are stumbling blocks and increasingly unsatisfying, since they have ceased to function”, in part because of the Academy’s willingness to step outside its comfort zone and award the prize to a popular “singer/songwriter”.

When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, the poet Nora Gomringer expressed her satisfaction at the recognition thus afforded not only poetry, but in particular songwriting, which she identified as the very wellspring and guarantee of literature, citing in her appraisal such classical forebears as Sappho and Homer. In an article published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Gomringer mocked the conventional Western view of letters, a canon founded on prose and the novel, and now challenged by the award to Bob Dylan: “Literature is serious, it is beautiful, it is a vehicle for the noble and the grand; poetry is for what is light, for the aesthetically beautiful, it can be hermetic or tender, it can tell its story in a ballad and, if especially well made, can invite composers to set it to music…”. But “such categories”, she went on to suggest, “are stumbling blocks and increasingly unsatisfying, since they have ceased to function”, in part because of the Academy’s willingness to step outside its comfort zone and award the prize to a popular “singer/songwriter”.

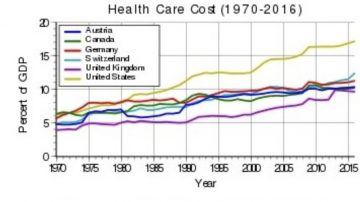

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

Fifty years ago, when healthcare expenditures were a mere 6% of US GDP, Martin Feldstein was afraid that the seemingly imminent adoption of some form of national health insurance would cause health care spending to grow unchecked.

As I sit here marveling at the inexorability of deadlines, even in the midst of holiday cheer, I consider that I should, in the absence of time for research ventures, write about “what I know.” Isn’t that the default advice for people who don’t know what to write about and don’t want to come across as false? Well, I spend at least half of my time, and most of my psychic energy, on tasks stemming from being a mother. But do I “know” anything about it? For example, how do you get your child to become a good person, and by that I don’t mean compliant or obedient, but ethical? I spend a lot of time fretting about it, but I don’t know if I have any answers.

As I sit here marveling at the inexorability of deadlines, even in the midst of holiday cheer, I consider that I should, in the absence of time for research ventures, write about “what I know.” Isn’t that the default advice for people who don’t know what to write about and don’t want to come across as false? Well, I spend at least half of my time, and most of my psychic energy, on tasks stemming from being a mother. But do I “know” anything about it? For example, how do you get your child to become a good person, and by that I don’t mean compliant or obedient, but ethical? I spend a lot of time fretting about it, but I don’t know if I have any answers.

In 1885 Mary Terhune, a mother and published childcare adviser, ended her instructions on how to give baby a bath with this observation:

In 1885 Mary Terhune, a mother and published childcare adviser, ended her instructions on how to give baby a bath with this observation: