by Jeroen Bouterse

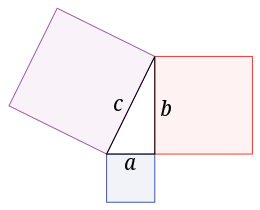

I have some very simple New Year’s resolutions, and some that require an entire column to spell out. One example of the latter is that I want to make a subtle but meaningful change in how I talk to my (middle and high school) math students about proofs.

I have some very simple New Year’s resolutions, and some that require an entire column to spell out. One example of the latter is that I want to make a subtle but meaningful change in how I talk to my (middle and high school) math students about proofs.

First, I need to be open about the fact that talking about proof in mathematics comes with an especially strong impostor syndrome: as a secondary school teacher, who am I to talk about the nature and limits of deductive reasoning in a discipline of which I have barely scratched the surface? I know high school proofs of high school mathematical concepts; I am vaguely aware that people much cleverer than I have tried to reduce all mathematical claims to analytical (logical) truths, or at least to a limited set of axioms; and I believe that after having mentioned this, I have to name-drop Gödel as the person who has supposedly put a stop to these projects, even though I have never studied his incompleteness theorem and doubt I would be able accurately to judge its relevance and meaning. That’s about it.

Usually, doubts like these are something to keep hidden in a light-hearted column like this, because they waste space and look self-absorbed. In this case, however, I think they are relevant, because I suspect I will not be the only one who (1) is by no means an expert on mathematical logic, and (2) still has some intuitive convictions about the special relation between mathematics and provability. Most of us, when we think about mathematics and proof, think of high school or undergraduate mathematics. I think it is fair to say that this is the most culturally prominent face of mathematics: the concepts almost all of us have been taught, or at least heard about, and the discourses surrounding the teaching of those concepts.

These discourses will depend in part on the teachers you have encountered, but I’ll go out on a limb here and speculate that most mathematics teachers will have told most of their classes, at some point, that “in mathematics we believe things because we can prove them”. I know I have made comments in that spirit. I have also come to feel a bit uncomfortable about them. Let me tell you why. Read more »

We find ourselves always in the middle of an experience. But it’s what we do next – how we characterize the experience – that lays down a host of important and almost subterranean conditions. Am I sitting in a chair, gazing out the dusty window into a world of sunlight, trees, and snow? Am I meditating on the nature of experience? Am I praying? Am I simply spacing out? Depending on which way I parse whatever the hell I’m up to, my experience shifts from something ineffable (or at any rate, not currently effed) to something meaningful and determinate, festooned with many other conversational hooks and openings: “enjoying nature”, “introspecting”, “conversing with God”, “resting”, “procrastinating”, and so on. Putting the experience into words tells me what to do with it next.

We find ourselves always in the middle of an experience. But it’s what we do next – how we characterize the experience – that lays down a host of important and almost subterranean conditions. Am I sitting in a chair, gazing out the dusty window into a world of sunlight, trees, and snow? Am I meditating on the nature of experience? Am I praying? Am I simply spacing out? Depending on which way I parse whatever the hell I’m up to, my experience shifts from something ineffable (or at any rate, not currently effed) to something meaningful and determinate, festooned with many other conversational hooks and openings: “enjoying nature”, “introspecting”, “conversing with God”, “resting”, “procrastinating”, and so on. Putting the experience into words tells me what to do with it next.

Forever is a long time.

Forever is a long time.

Lili Marleen is one of the best known songs of the twentieth century. A plaintive expression of a soldier’s desire to be with his girlfriend, it is indelibly associated with World War II, in part because it was popular with soldiers on both sides. It was

Lili Marleen is one of the best known songs of the twentieth century. A plaintive expression of a soldier’s desire to be with his girlfriend, it is indelibly associated with World War II, in part because it was popular with soldiers on both sides. It was  Marlene Dietrich, who worked tirelessly during world war two entertaining allied troops, also recorded both a

Marlene Dietrich, who worked tirelessly during world war two entertaining allied troops, also recorded both a

While waiting, shivering and jetlagged, for a train home from the Paris airport this week, I alternately stared into space and checked the train timetables. My train was an hour late. I later learned, thanks to the friendliness of a fellow traingoer, that the train had hit a deer.

While waiting, shivering and jetlagged, for a train home from the Paris airport this week, I alternately stared into space and checked the train timetables. My train was an hour late. I later learned, thanks to the friendliness of a fellow traingoer, that the train had hit a deer.

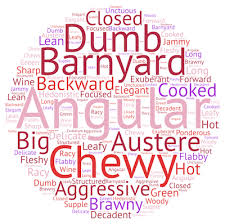

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

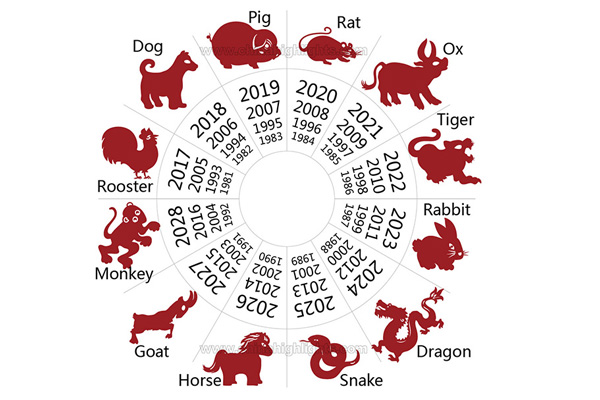

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it.

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it. Schoolteachers across the grades are responsible for teaching their students how to write. Their essential pedagogical role is instrumental. With particular attention paid to format, grammar, spelling, and syntax, students ideally learn to write what they know, think, or have learned. It matters little if the student is in a class for “creative writing” or “composition,” writing is taught and practiced as a way to record thoughts, compose ideas in a coherent manner, and clearly communicate information. A student’s writing is then assessed for how well she adhered to these instrumental standards while the teacher is assessed for how well she adhered to the standards of instrumental teaching.

Schoolteachers across the grades are responsible for teaching their students how to write. Their essential pedagogical role is instrumental. With particular attention paid to format, grammar, spelling, and syntax, students ideally learn to write what they know, think, or have learned. It matters little if the student is in a class for “creative writing” or “composition,” writing is taught and practiced as a way to record thoughts, compose ideas in a coherent manner, and clearly communicate information. A student’s writing is then assessed for how well she adhered to these instrumental standards while the teacher is assessed for how well she adhered to the standards of instrumental teaching.