by Joan Harvey

The radio music is smooth now, sentimental, semi-classic in the popular vein…music something like a golden bell, promising that tomorrow will be better. Jazz, good jazz, tells no such lies. —Charles Wright, The Messenger

Recently, in an independent bookstore in a city I was visiting, one of the books I randomly scooped up to weigh down my luggage on the way home was The Collected Novels of Charles Wright, with an introduction by Ishmael Reed. The confusing thing was, had I heard of him? It seemed to me that of course I had, but there is a famous American poet named Charles Wright and this is not that man. There was also of course Richard Wright; the first novel in this collection is dedicated in part to him. There’s Charles White, the artist, whose work I happened to see on this same trip. But the Charles Wright of these novels is Charles Stevenson Wright (1932-2008). I later looked this collection up on Amazon. There are zero reader reviews of this edition. The last copyright before this was 1993. And yet he’s back in print, or still in print; there are editions of the novels separately. Very little has been written about him. Yet Wright’s writing felt familiar, as if he were an old friend.

The collection contains Wright’s three novels. The first, The Messenger, is from 1963, The Wig from 1966, and Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About from 1973. The Wig is satirical and fictional; Reed cites it as an influence. Some think it is a better book than the other two, which are mostly made of vignettes of Wright’s direct experience. I prefer the more autobiographical books that bookend the satire. In Absolutely Nothing Wright mentions having a drink with Langston Hughes in the Cedar Tavern just before Hughes died. Wright remembers Hughes saying, “The Wig disturbed me, and it’s a pity you can’t write another one like it. But don’t. Write another little book like The Messenger” (278). Although The Wig is a scathing and often brilliant satire, I think Hughes was right. Read more »

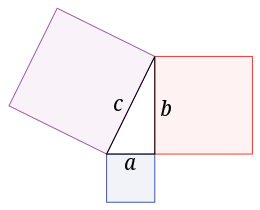

I have some very simple New Year’s resolutions, and some that require an entire column to spell out. One example of the latter is that I want to make a subtle but meaningful change in how I talk to my (middle and high school) math students about proofs.

I have some very simple New Year’s resolutions, and some that require an entire column to spell out. One example of the latter is that I want to make a subtle but meaningful change in how I talk to my (middle and high school) math students about proofs.

We find ourselves always in the middle of an experience. But it’s what we do next – how we characterize the experience – that lays down a host of important and almost subterranean conditions. Am I sitting in a chair, gazing out the dusty window into a world of sunlight, trees, and snow? Am I meditating on the nature of experience? Am I praying? Am I simply spacing out? Depending on which way I parse whatever the hell I’m up to, my experience shifts from something ineffable (or at any rate, not currently effed) to something meaningful and determinate, festooned with many other conversational hooks and openings: “enjoying nature”, “introspecting”, “conversing with God”, “resting”, “procrastinating”, and so on. Putting the experience into words tells me what to do with it next.

We find ourselves always in the middle of an experience. But it’s what we do next – how we characterize the experience – that lays down a host of important and almost subterranean conditions. Am I sitting in a chair, gazing out the dusty window into a world of sunlight, trees, and snow? Am I meditating on the nature of experience? Am I praying? Am I simply spacing out? Depending on which way I parse whatever the hell I’m up to, my experience shifts from something ineffable (or at any rate, not currently effed) to something meaningful and determinate, festooned with many other conversational hooks and openings: “enjoying nature”, “introspecting”, “conversing with God”, “resting”, “procrastinating”, and so on. Putting the experience into words tells me what to do with it next.

Forever is a long time.

Forever is a long time.

Lili Marleen is one of the best known songs of the twentieth century. A plaintive expression of a soldier’s desire to be with his girlfriend, it is indelibly associated with World War II, in part because it was popular with soldiers on both sides. It was

Lili Marleen is one of the best known songs of the twentieth century. A plaintive expression of a soldier’s desire to be with his girlfriend, it is indelibly associated with World War II, in part because it was popular with soldiers on both sides. It was  Marlene Dietrich, who worked tirelessly during world war two entertaining allied troops, also recorded both a

Marlene Dietrich, who worked tirelessly during world war two entertaining allied troops, also recorded both a

While waiting, shivering and jetlagged, for a train home from the Paris airport this week, I alternately stared into space and checked the train timetables. My train was an hour late. I later learned, thanks to the friendliness of a fellow traingoer, that the train had hit a deer.

While waiting, shivering and jetlagged, for a train home from the Paris airport this week, I alternately stared into space and checked the train timetables. My train was an hour late. I later learned, thanks to the friendliness of a fellow traingoer, that the train had hit a deer.

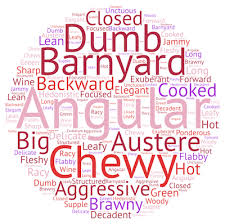

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

Wine writers, especially those who write wine reviews, are often derided for the flowery, overly imaginative language they use to describe wines. Some of the complainants are consumers baffled by what descriptors such as “brooding” or “flamboyant” might mean. Other complainants are experts who wish wine language had the precision of scientific discourse. The Journal of Wine Economists

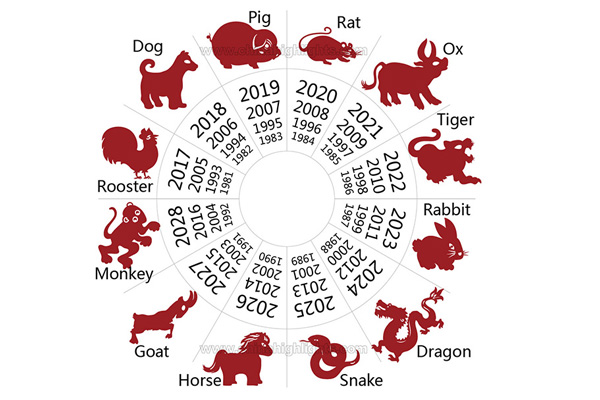

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it.

In the Chinese calendar, 2015 was the year of the sheep. I’m a sheep, and I briefly got into it. When you’re a sheep, you gotta own it.