by Pranab Bardhan

Many find fault with liberal democracy because it exacerbates inequality, particularly when wedded to unbridled capitalism. But inequality has been rampant in authoritarian countries as well, with or without capitalism. Many non-capitalist countries in actual history have been friendly neither to liberty nor equality, never mind the soaring rhetoric, whereas some liberal democracies have provided their alert citizenry with the means of taming the harshness of capitalism, showing the possibility of liberty and equality working together at least up to some distance.

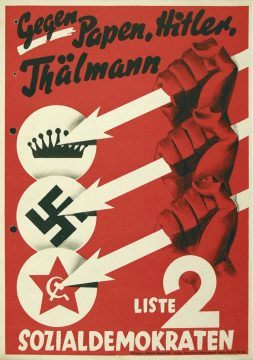

Others find fault with liberal democracy because its emphasis on individual freedom may loosen community bonding and rootedness, but ‘liberty’ and ‘fraternity’ need not work at cross-purposes, and one should keep in mind that communitarian excesses without liberalism can hurt interests of minority and dissident or non-conformist groups and individual autonomy. For a discussion of these issues see my piece, “Can the Local Community Save Liberal Democracy?”. Yet why is liberal democracy so fragile? All around us demagogues rule even in traditional bastions of democracy; and majoritarianism so easily hollows out democracies and keeps only the shell (and even sometimes triumphantly gets that shell described by the oxymoronic term ‘illiberal democracy’).

In my article, “Coping with Resurgent Nationalism” I have suggested that if the constitution in some democratic countries incorporates liberal inclusive values and is reasonably difficult to change, it can provide the basis of some form of civic nationalism (or what Habermas called ‘constitutional patriotism’) that may resist the marauding forces of majoritarianism or exclusivist ethnic nationalism. But the ethnic nationalist leaders are so adept at whipping up our primordial or visceral evolutionary defensive-aggressive urge to fight against so-called ‘enemy’ groups, that such resistance is currently crumbling in many countries –for example, conspicuously in India under the onslaught of Hindu nationalism, even after several decades of reasonably successful civic nationalism based on values of pluralism enshrined in the constitution and undergirded by centuries of folk-syncretic tradition of tolerance and pluralism of faith among the common people. Read more »

Where is philosophy in public life? Can we point to how the world in 2020 is different than it was in 2010 or 1990 because of philosophical research?

Where is philosophy in public life? Can we point to how the world in 2020 is different than it was in 2010 or 1990 because of philosophical research?

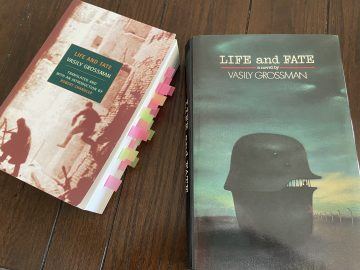

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in a typhoon of steel and firepower without precedent in history. In spite of telltale signs and repeated warnings, Joseph Stalin who had indulged in wishful thinking was caught completely off guard. He was so stunned that he became almost catatonic, shutting himself in his dacha, not even coming out to make a formal announcement. It was days later that he regained his composure and spoke to the nation from the heart, awakening a decrepit albeit enormous war machine that would change the fate of tens of millions forever. By this time, the German juggernaut had advanced almost to the doors of Moscow, and the Soviet Union threw everything that it had to stop Hitler from breaking down the door and bringing the whole rotten structure on the Russian people’s heads, as the Führer had boasted of doing.

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.

Ryan Ruby is a novelist, translator, critic, and poet who lives, as I do, in Berlin. Back in the summer of 2018, I attended an event at TOP, an art space in Neukölln, where along with journalist Ben Mauk and translator Anne Posten, his colleagues at the Berlin Writers’ Workshop, he was reading from work in progress. Ryan read from a project he called Context Collapse, which, if I remember correctly, he described as a “poem containing the history of poetry.” But to my ears, it sounded more like an academic paper than a poem, with jargon imported from disciplines such as media theory, economics, and literary criticism. It even contained statistics, citations from previous scholarship, and explanatory footnotes, written in blank verse, which were printed out, shuffled up, and distributed to the audience. Throughout the reading, Ryan would hold up a number on a sheet of paper corresponding to the footnote in the text, and a voice from the audience would read it aloud, creating a spatialized, polyvocal sonic environment as well as, to be perfectly honest, a feeling of information overload. Later, I asked him to send me the excerpt, so I could delve deeper into what he had written at a slower pace than readings typically afford—and I’ve been looking forward to seeing the finished project ever since. And now that it is, I am publishing the first suite of excerpts from Context Collapse at Statorec, where I am editor-in-chief.

The case for men’s rights follows straightforwardly from the feminist critique of the structural injustice of gender rules and roles. Yes, these rules are wrong because they oppress women. But they are also wrong because they oppress men, whether by causing physical, emotional and moral suffering or callously neglecting them. Unfortunately the feminist movement has tended to neglect this, assuming that if women are the losers from a patriarchal social order, then men must be the winners.

The case for men’s rights follows straightforwardly from the feminist critique of the structural injustice of gender rules and roles. Yes, these rules are wrong because they oppress women. But they are also wrong because they oppress men, whether by causing physical, emotional and moral suffering or callously neglecting them. Unfortunately the feminist movement has tended to neglect this, assuming that if women are the losers from a patriarchal social order, then men must be the winners.