Self-portrait with my wife in a reflection from a car window during a brief walk in the sun just outside our house three days ago.

Apocalyptic Pop Culture in the Age of a Pandemic

by Mindy Clegg

The taste for the end times as a dramatic backdrop well preceded our current pandemic lock-down, but now seems as good a time as any to explore the popularity of end-of-time dramas as any other. Perhaps we can take some solace from a discussion of others surviving worse situations than our own, even if fictional. Philosopher and pop culture theorist Slavoj Žižek (or it might have been Fredrick Jameson) once noted that the popularity of apocalyptic culture tended to be driven by the all-encompassing power of our current global system, noting that it’s easier for us to imagine the world’s end rather than it’s transformation.1 This seems to break with earlier popular culture that imagined some level of continuity between our present and the future, such as Star Trek. If today we have a harder time imagining productive change to our globalized system, at least our visions of its collapse are numerous and offer compelling viewing. The Walking Dead comic and TV series are a prime example of that sort of entertainment. I argue here that although the series and comic seem on the surface to explore only the collapse of our modern systems of governance and our globalized economy, the focus instead rests on what we keep and what we leave behind as we rebuild in the wake of some kind of wide-spread devastation. In many ways, the Walking Dead offers an alternative to ideologies like the Milton Friedman “shock doctrine” that turns disasters into fodder for privatization.2

Just a note for fans of the show or comic: I’ll include spoilers here for what I’ve watched thus far and for the comic, as that has recently concluded. Read more »

Will the Taste Revolution Survive?

by Dwight Furrow

I’m sitting in front of my window on the world sipping a disappointing Cabernet Sauvignon from Napa Valley and thinking about travel plans for next summer and fall. I’m proceeding as if everything were normal knowing full well they won’t be, especially not with our “leadership”. Every time I try to write something insightful about wine, these lyrics from the bard of Duluth run through my mind:

I’m sitting in front of my window on the world sipping a disappointing Cabernet Sauvignon from Napa Valley and thinking about travel plans for next summer and fall. I’m proceeding as if everything were normal knowing full well they won’t be, especially not with our “leadership”. Every time I try to write something insightful about wine, these lyrics from the bard of Duluth run through my mind:

Here comes the blind commissioner

They’ve got him in a trance

One hand is tied to the tightrope walker

The other is in his pants

And the riot squad they’re restless

They need somewhere to go

As Lady and I look out tonight

From Desolation Row

—Bob Dylan, Desolation Row

There are many tragedies unfolding as Covid-19 ravages the planet. With the massive loss of life and livelihood, the fate of the wine and restaurant industry is not among the worst outcomes, but it nevertheless saddens me when I think about it. Small, artisan wineries, independent restaurants and their employees are going to take a big hit. That’s a lot of skill, creativity, imagination and determination gone to waste. The chains and mammoth, commercial wine companies will survive by doing what well- financed firms with market power and lobbyists do. But it will be hard for the little guy to survive in a business as tough as the restaurant business or the artisan winery business. (I’m writing from the perspective of the U.S. but I imagine the situation is similar worldwide.) These small businesses are the heart and soul of the wine and restaurant industries and they face an uncertain future. Read more »

Monday, March 30, 2020

Sole Craft as Soulcraft

by Eric J. Weiner

Shoes could save your life. —Edith Grossman, survivor of the Auschwitz death camp

These boots are made for walking/And that’s just what they’ll do/One of these days these boots are gonna walk all over you —Nancy Sinatra

As I had never seen my shoes before, I set myself to study their looks, their characteristics, and when I stir my foot, their shapes and their worn uppers. I discover that their creases and white seams give them expression — impart a physiognomy to them. Something of my own nature had gone over into these shoes; they affected me, like a ghost of my other I — a breathing portion of my very self —Knut Hamsun

Quarantined, sheltered, holed-up, bunkered, hiding, homebound, trapped–whatever you want to call it–I am, probably (hopefully) like you, socially isolated from everyone but my family, trying to do my part in “flattening the curve” on a virus that seems intent on overwhelming a system ill-equipped to deal with such a thing. Like the prisoner who resorts to counting the pockmarks on the cement wall of his cell to pass the time, I have used some of my new, spare time to take an account of my collection of shoes and boots. But unlike Derrida or Heidegger in regards to Vincent Van Gogh’s famous painting of boots, I have absolutely no desire to be profound or provocative. I simply and admittedly have a bit of a shoe and boot “problem” that I would like to discuss; not sneakers or trainers—never caught the bug—but handcrafted leather footwear that typically go from very expensive to “holy crap that’s a lot of money for boots!” My wife doesn’t understand it. “Another pair of boots?” she sneers as I unapologetically remove my latest purchase from its sturdy cardboard case; a stunning pair of Horween shell cordovan lace wing-tip boots, color number 8, with Goodyear welts, lug soles and copper rivets, handmade in the USA by one of the oldest family-owned shoe/boot-makers in the country. They ain’t cheap but they’re not “holy crap” expensive either. They are beautiful and rough, sophisticated and classic, yet in no way arrogant or pretentious and will be around, if properly cared for, long after I am dead. Seems like a deal to me.

Quarantined, sheltered, holed-up, bunkered, hiding, homebound, trapped–whatever you want to call it–I am, probably (hopefully) like you, socially isolated from everyone but my family, trying to do my part in “flattening the curve” on a virus that seems intent on overwhelming a system ill-equipped to deal with such a thing. Like the prisoner who resorts to counting the pockmarks on the cement wall of his cell to pass the time, I have used some of my new, spare time to take an account of my collection of shoes and boots. But unlike Derrida or Heidegger in regards to Vincent Van Gogh’s famous painting of boots, I have absolutely no desire to be profound or provocative. I simply and admittedly have a bit of a shoe and boot “problem” that I would like to discuss; not sneakers or trainers—never caught the bug—but handcrafted leather footwear that typically go from very expensive to “holy crap that’s a lot of money for boots!” My wife doesn’t understand it. “Another pair of boots?” she sneers as I unapologetically remove my latest purchase from its sturdy cardboard case; a stunning pair of Horween shell cordovan lace wing-tip boots, color number 8, with Goodyear welts, lug soles and copper rivets, handmade in the USA by one of the oldest family-owned shoe/boot-makers in the country. They ain’t cheap but they’re not “holy crap” expensive either. They are beautiful and rough, sophisticated and classic, yet in no way arrogant or pretentious and will be around, if properly cared for, long after I am dead. Seems like a deal to me.

It’s both true and a fact that a good boot or shoe can make a man just as quickly as a poorly manufactured one can break him. Slip a hand-crafted Chromexcel leather boot on a man choking in the grip of life’s callous hand, lace it snug around his foot and ankle, and he just might stand up even taller than God made him and, like a slave breaking his chains of bondage, throw that hand off as if it was nothing more than a bit of schmutz on his collar. I completely understand why soldiers and cowboys wanted to die with their boots on–dignity in death, meaning in life; take my last breath, just don’t take my damn boots! Read more »

The Useful and the Sweet

by Rafaël Newman

Some years ago, a friend told me about his dilettantish taste for nicotine, indulgence in which, however, he noted ruefully, was often thwarted by his young daughter. He supposed the vehemence of her protests derived, simply, from a concern for his health – to which I responded, perhaps: but that there might also be a further factor. His daughter, I reminded him, was just barely prepubescent, and thus newly arrived in what classical psychoanalysts call the “latency phase”, in which the para-erotic pulsions characterizing the various stages of her psychosexual development to date, and directed at her opposite-sex parent, the putative object of her nascent desire, are in retreat under the dawning realization that she is unlikely to be successful in her Oedipal struggle; and so she begins instead to bend to the will of a superego offering a compensatory identification with her triumphant rival, her mother. (This was before I had read Didier Eribon.) As a consequence, I concluded, his daughter was in the midst of developing prohibitive feelings of disgust at the merest suggestion of the desire she was busy repressing, and was thus likely to react with exaggerated horror at any sign of eroticism on the part of her erstwhile object.

Some years ago, a friend told me about his dilettantish taste for nicotine, indulgence in which, however, he noted ruefully, was often thwarted by his young daughter. He supposed the vehemence of her protests derived, simply, from a concern for his health – to which I responded, perhaps: but that there might also be a further factor. His daughter, I reminded him, was just barely prepubescent, and thus newly arrived in what classical psychoanalysts call the “latency phase”, in which the para-erotic pulsions characterizing the various stages of her psychosexual development to date, and directed at her opposite-sex parent, the putative object of her nascent desire, are in retreat under the dawning realization that she is unlikely to be successful in her Oedipal struggle; and so she begins instead to bend to the will of a superego offering a compensatory identification with her triumphant rival, her mother. (This was before I had read Didier Eribon.) As a consequence, I concluded, his daughter was in the midst of developing prohibitive feelings of disgust at the merest suggestion of the desire she was busy repressing, and was thus likely to react with exaggerated horror at any sign of eroticism on the part of her erstwhile object.

“You mean,” he said, “she interprets my cigarette smoking as a manifestation of such eroticism?”

“Yes,” I said. “Because it involves you repeatedly touching yourself with pleasure.”

I’ve been recalling that conversation a lot lately, as the injunction, issued by a global superego, to avoid doing precisely this – touching oneself, specifically one’s face – has made many of us hyper-aware of our tendency to do so, and lent an ostensibly banal behavior the allure of the forbidden. Read more »

Monday Poem

Like The Old Harry

….. –for my father, Jim

My father was an opaque poet

of blue collar verse

who’d sling odd terms

from the corner of his mouth

opposite the one holding

the lip-gripped cigarette

issuing curlicues of smoke

which circled his cocked head

his eyes squinting from their sting

his playful gags filled earcups

from which I, with fresh curiosity, drank

to quench a thirst for the secret

stuff of words

“Up Laundry Hill,”

he’d say to my question,

“Hey, dad,where you goin’?”

as if the place he was headed beyond the door

was a high meadow in which my grandmother

with a bar of brown soap

might scrub shirts by a slow river

and hang them to dry on lines strung tree to tree

as an August sun drenched them with a bounty

of white light and a day’s-worth of heat

Like the old Harry was his expression

for the speed of a world that moved

like the Old Harry as I, in new Keds

ran, not like the wind, but like the Old Harry,

a quick little shit on white rubber soles

consuming the universe of our yard

in nanoseconds

Whoever Old Harry was my dad knew him well—

knew he could outrun light when it came down to it

despite the equation upon which Einstein,

regarding questions of velocity, stood

—there’s more to earth than science:

the music of syllables

the humor in their arrangements

the unexpected flash of odd conjunctions

the comfort of the syntax of tradition

the sudden crack of their smart whip

which sometimes sends us like the Old Harry,

in a sprint, up Laundry Hill

Jim Culleny

5/3/11

Sitzfleisch and a Movie in the Time of Plague

by Michael Liss

I am one of those people who cannot sit still. I wasn’t good at it as a child, and as the decades pass, every indication is that I will never be good at it. I suspect I inherited this from my father, who lacked a single iota of Sitzfleisch, and have passed on the gene to one of my children (no need to name names here, she knows who she is and who to blame.)

I am one of those people who cannot sit still. I wasn’t good at it as a child, and as the decades pass, every indication is that I will never be good at it. I suspect I inherited this from my father, who lacked a single iota of Sitzfleisch, and have passed on the gene to one of my children (no need to name names here, she knows who she is and who to blame.)

I did fully disclose this to my wife before we were married, not that she needed to be told. She hangs in there, with occasional moments of thoroughly merited exasperation. Weekdays tend to take care of themselves, as we both work fairly long hours. Weekends, on the other hand, can be problematic, so I’m fairly sure she likes it when I leave to go running in the park with my group. As I’m not the greyhound I used to be, this can take quite a bit of time, especially when you add in a stop on the way back for some empty calories. Before you know it, it’s almost Noon. Sitzfleisch problem solved, at least until 1:30.

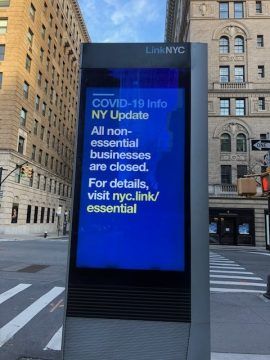

Of course, this was all before Coronavirus, all before I was deemed “non-essential” and even officially old. I’m not sure where this “old” nonsense came from, but the solicitude for my health and wellbeing merely as a function of an arbitrary number is a little hard to take. All of a sudden there seem to be an awful lot of things I’m not supposed to be doing. I never thought “aging in place” was meant to be taken literally.

Of course, this was all before Coronavirus, all before I was deemed “non-essential” and even officially old. I’m not sure where this “old” nonsense came from, but the solicitude for my health and wellbeing merely as a function of an arbitrary number is a little hard to take. All of a sudden there seem to be an awful lot of things I’m not supposed to be doing. I never thought “aging in place” was meant to be taken literally.

This is such a petty complaint. In my City, my Mighty Gotham, we are apparently all aging in place, all taking care by taking shelter. This just doesn’t suit us well. Sitzfleisch is for suburbanites.…the kind of folks who drive a football field’s distance for a quart of milk and have 5,000 square-foot homes with enormous refrigerators, storage space, and a game room where the kids can fight with each other from another zip code. Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. Landing; Mood. Boston, September 2012.

Digital photograph.

On the Road: Coping with Calamity

by Bill Murray

Two minutes after the explosion the fire station alarm rang. The firefighters who scrambled from sleep to the scene, along with the regular overnight shift at reactor four, were among the first fatally irradiated. Unquestioned heroes, they battled the blazes until dawn with no special training for a nuclear accident, in shirtsleeves, using only conventional firefighting methods. They walked amid flaming, radioactive graphite.

Two minutes after the explosion the fire station alarm rang. The firefighters who scrambled from sleep to the scene, along with the regular overnight shift at reactor four, were among the first fatally irradiated. Unquestioned heroes, they battled the blazes until dawn with no special training for a nuclear accident, in shirtsleeves, using only conventional firefighting methods. They walked amid flaming, radioactive graphite.

The power station fire brigade arrived first. Lieutenant Volodymyr Pravik, their commander, saw right away he needed help and called in fire brigades from the little towns of Pripyat and Chernobyl. When Pravik died thirteen days later he was a month shy of age twenty-four.

“We arrived there at 10 or 15 minutes to two in the morning,” said fire engine driver Grigorii Khmal.

“We saw graphite scattered about. Misha asked: Is that graphite? I kicked it away. But one of the fighters on the other truck picked it up. It’s hot, he said. The pieces of graphite were of different sizes, some big, some small enough to pick them up….

“We didn’t know much about radiation. Even those who worked there had no idea. There was no water left in the trucks. Misha filled a cistern and we aimed the water at the top. Then those boys who died went up to the roof – Vashchik, Kolya and others, and Volodya Pravik…. They went up the ladder … and I never saw them again.”

Another fireman told the BBC, “It was dark because it was night. On the other hand, you could see and even recognize a person from 10 to 15 meters. It was if (sic) the sun was rising, but with a strange light.”

They climbed to the roof of what was left of reactor four, preventing fire from spreading to the other three reactors and so preventing what could have been a truly ghastly night. By 5:00 a.m. all the fires were out save for the one in the reactor. That fire burned for ten days. It took 5000 tons of sand, boron, dolomite and clay dropped from helicopters to put it out. Read more »

Essential Services (a very short story)

by Amitava Kumar

Every day that week a line formed outside the liquor store by noon. Those in line stood six feet apart, checking their phones, or reading a book, or looking up at the trees. Twelve people were allowed at a time into the liquor store.

A man and woman, wearing masks and gloves, arrived from different directions. The man, who might have been in his twenties and whose mask was blue colored, made a flourish with a gloved hand and let the woman take the place ahead of him. For a moment, he studied the back of the woman’s head. She had blonde streaks in her hair.

‘You weren’t answering the phone last night,’ the young woman said to him, turning. ‘Do you think it is easy for me to step out like this?’

Her companion hadn’t stopped smiling under his mask ever since she arrived.

He now said, ‘I’ve heard that the wait is longer in the line outside the CVS on South Hill Road. Your father must need medicines. Let’s meet there tomorrow.’

Ask a Hermit, Part III

by Holly A. Case (Interviewer) and Tom J. W. Case (Hermit)

by Holly A. Case (Interviewer) and Tom J. W. Case (Hermit)

The following is the continuation of an interview with Tom, a pilot who has largely withdrawn to a small piece of land in rural South Dakota. Parts I and II can be found here and here.

Interviewer: I’d like to ask how you would tell the story of your inner jukebox—perhaps under the title “The Inner Jukebox: A Bildungsroman.”

Hermit: Ah, the inner jukebox, its bearings rusty and contacts dusty. That thing used to roll on an endless reel, telling me and shaping how I feel.

Music, I really used to think, is one of mankind’s greatest achievements. Now I just think less, it seems, or about different things. But even as I give music less thought, it surely is very special.

Music can fit a mood, bend or even break a mood, make a new mood, take you places—what a thing! But at the same time, there is always the chance of going missing as in other ways I have described. In no way have I shunned or avoided music, but I do not seek its warp-voyager quality any longer. I must say that I am not beyond being grabbed and taken for a ride from time to time, however.

The soundtrack you mentioned, I used to make so many playlists to fit time, place, and mood, and it never failed that by the time I had finished making the perfect playlist, it no longer fit those things. I might conclude that it has everything to do with the aforementioned coloring; that the more one truly accepts their immediate surrounding and circumstance, there might just not be a track cued up (unless on an elevator, help us).

All of that said, it can be counted on that I am nearly always narrating my plodding with ditties and tunes spontaneously coined.

Interviewer: On the subject of where the mind goes (and warp-voyagers), what are the thought patterns that recur in hermitude?

Hermit: This is perhaps the one area in which I struggle the most. Thought.

I said just before that I think less, or about other things now. Not true, that, upon reflection. I interact with my thoughts less, but there is no evidence that I think less. Thank you for reminding me. Read more »

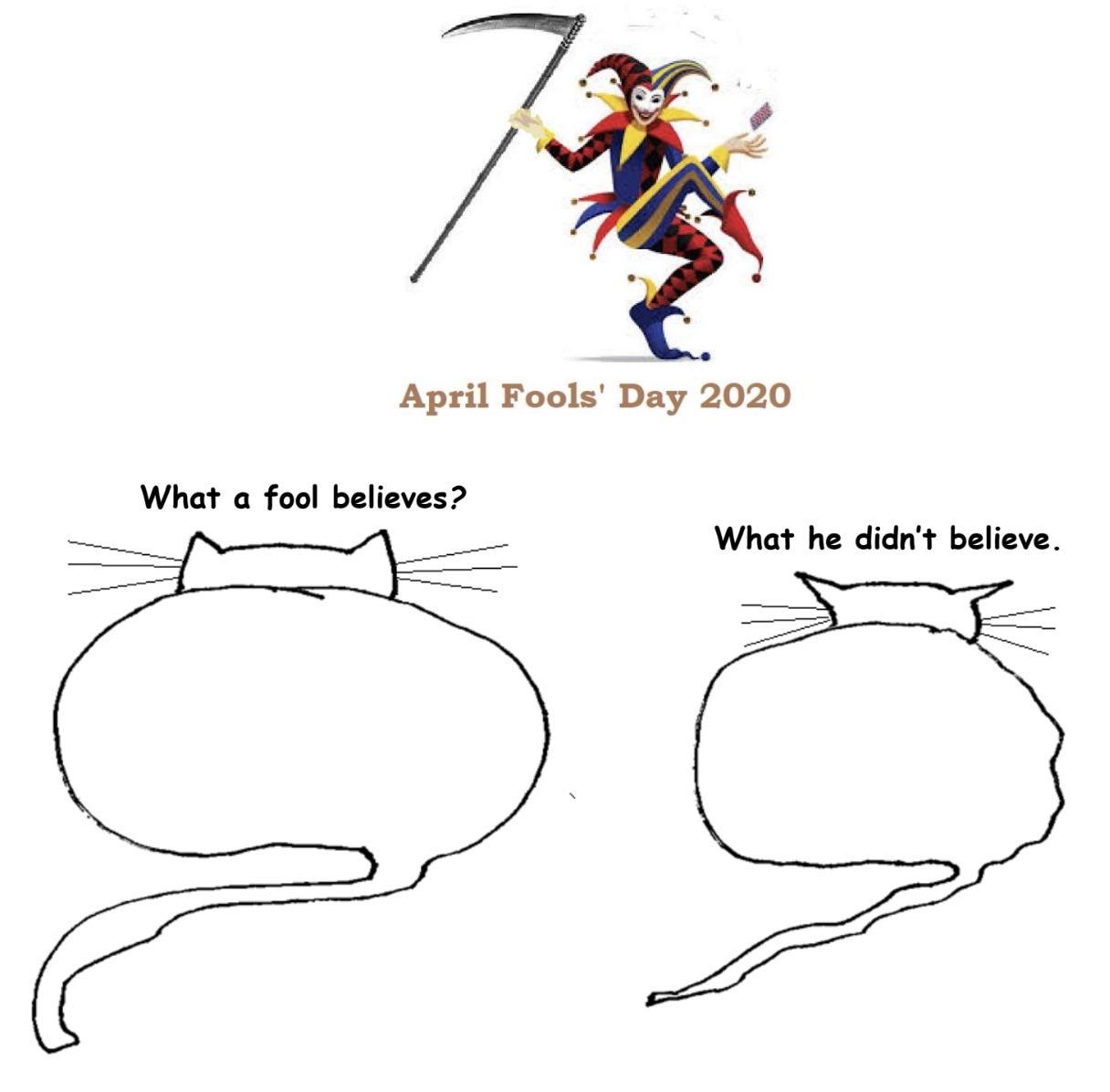

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Technology in a time of Covid-19

by Sarah Firisen

I’ve been telecommuting on and off for over 17 years. I first started working from home because I’d moved 150 miles away from the company I’d been contracting for over the previous 4 years. Back then, I worked in a small team that was part of a larger team in a huge corporation. My immediate boss was very supportive of my new working arrangement, but he had a peer, who even though she had no responsibility for my work, felt the need to have her say to their mutual boss. Her thoughts went along lines of, “how do we know she’s really working when she never comes into the office?”, to which my boss said, “well someone is getting all the work done, so if it isn’t Sarah, who is it?”. This conversation seems almost quaint nowadays, when even before the current pandemic, a decent amount of the white-collar professional workforce worked at least occasionally from home. And now of course, we’ve all been thrust into a great social experiment to see just how productive, perhaps more rather than less even, the entire workforce will be working remotely. Everyone else is now catching up to what I’ve known for a long time: it’s pretty nice to not have to deal with the daily commute and that time can really be used more productively than fighting for space on mass transit; you have to be at least somewhat disciplined to make sure you only go so many days working in the same pjs you’ve been in all week; working from home can give you a lot of time to multitask life stuff like unloading the dishwasher while you’re listening to a conference call, but it can also be harder to draw boundaries between home and work life, and this takes some practice. Read more »

I’ve been telecommuting on and off for over 17 years. I first started working from home because I’d moved 150 miles away from the company I’d been contracting for over the previous 4 years. Back then, I worked in a small team that was part of a larger team in a huge corporation. My immediate boss was very supportive of my new working arrangement, but he had a peer, who even though she had no responsibility for my work, felt the need to have her say to their mutual boss. Her thoughts went along lines of, “how do we know she’s really working when she never comes into the office?”, to which my boss said, “well someone is getting all the work done, so if it isn’t Sarah, who is it?”. This conversation seems almost quaint nowadays, when even before the current pandemic, a decent amount of the white-collar professional workforce worked at least occasionally from home. And now of course, we’ve all been thrust into a great social experiment to see just how productive, perhaps more rather than less even, the entire workforce will be working remotely. Everyone else is now catching up to what I’ve known for a long time: it’s pretty nice to not have to deal with the daily commute and that time can really be used more productively than fighting for space on mass transit; you have to be at least somewhat disciplined to make sure you only go so many days working in the same pjs you’ve been in all week; working from home can give you a lot of time to multitask life stuff like unloading the dishwasher while you’re listening to a conference call, but it can also be harder to draw boundaries between home and work life, and this takes some practice. Read more »

Monday Photo

Music to stay well by

by Dave Maier

I had planned to do another philosophy post this month, but I can hardly concentrate on such things about now and I bet you can’t either. Instead I’ve been hanging out on Bandcamp and blowing my savings supporting deserving artists and labels in this difficult time. What better time, in fact, to chill to some nice drony tuneage? Here’s a new set featuring mostly new discoveries but also a couple of potentially familiar names. As I recall, last time I worried that my sets had become too drony for a show traditionally dedicated mostly to space music, as Star’s End has been since the 1970s, when Berlin-school dinosaurs like Klaus Schulze and Tangerine Dream walked the earth, and I promised you some sequencers this time. And sequencers you shall have! (Even if not throughout.)

I had planned to do another philosophy post this month, but I can hardly concentrate on such things about now and I bet you can’t either. Instead I’ve been hanging out on Bandcamp and blowing my savings supporting deserving artists and labels in this difficult time. What better time, in fact, to chill to some nice drony tuneage? Here’s a new set featuring mostly new discoveries but also a couple of potentially familiar names. As I recall, last time I worried that my sets had become too drony for a show traditionally dedicated mostly to space music, as Star’s End has been since the 1970s, when Berlin-school dinosaurs like Klaus Schulze and Tangerine Dream walked the earth, and I promised you some sequencers this time. And sequencers you shall have! (Even if not throughout.)

I also did a (rather more wide-ranging) set for International Women’s Day (all female artists, naturally) on March 8. I didn’t write up notes for that one (seach the names on Bandcamp to learn more, and of course lend your own support), but before I forget, here’s the link to the Mixcloud page for that set:

Photos for a Time of Fever

Of course I would write about the COVID-19 pandemic. What else is there?

Two maybe three weeks ago I told myself, this changes everything. The next day I saw interviews and articles on that theme.

Everything will be different in two, three, years. Apocalypse. Singularity. Different. But what do I, what could I, know of that? Read more »

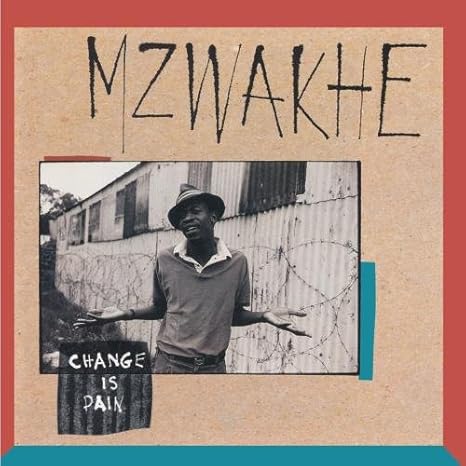

Stuck, Ch. 21. Changes: Charles Bradley, “Changes”

Stuck has been a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday since November. The table of contents with links to previous chapters is here.

by Akim Reinhardt

“Change is pain.” —South African poet Mzwakhe Mbuli

Manhattan always has been and always will be New York City’s geographic and economic center. But if you’re actually from New York, then you’re very likely not from Manhattan. Like me, you’re from one of the outer boroughs: The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, or Staten Island. And as far as we’re concerned, we’re the real New Yorkers. The natives with roots and connections, and the immigrants who are life-and-death dedicated to making them, not the tourists who come for a weekend or a dozen years before trundling back to America.

Manhattan always has been and always will be New York City’s geographic and economic center. But if you’re actually from New York, then you’re very likely not from Manhattan. Like me, you’re from one of the outer boroughs: The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, or Staten Island. And as far as we’re concerned, we’re the real New Yorkers. The natives with roots and connections, and the immigrants who are life-and-death dedicated to making them, not the tourists who come for a weekend or a dozen years before trundling back to America.

Manhattan below 125th Street (in the old days below 110th) is a playground for the wealthy, a postcard for tourists to visit. For the rest of us, it’s a job, it’s that place you have to take the subway to. Maybe that sounds like people from the outer boroughs have a chip on their shoulders. Trust me. They don’t. By and large, they’re very confident in their identity. They know exactly who they are. They’re New Yorkers. And you’re not.

However, between the boroughs themselves there can be a bit of a rivalry, and Manhattan’s not really part of that, because Manhattan is just its own thing, leaving the other four that jostle and jockey for New York street cred. For example, hip hop was practically born from tussles between the Bronx and Queens. But generally, it’s really not much of a contest. As a Bronx native, much to my chagrin, Brooklyn usually wins. Or at least, it used to.

The Bronx doesn’t have a lot to hang its hat on, but the things we have are big. The Yankees are the most successful sports franchise in world history. We have a big zoo, if you’re into that kinda thing. We created a pretty cool cheer. And of course we (that’s the proverbial “we,” not me in anyway) literally invented rap, later to be called hip hop, the world’s dominant musical and fashion force for at least a quarter-century now. But when I was a kid, it just didn’t seem to matter. Brooklyn still had a strut that the other boroughs could not match. Read more »

Monday, March 23, 2020

Paradoxes of Stoic Prescriptions

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Stoicism has been enjoying a renaissance lately. Popular books with Stoic advice are widespread, it’s being marketed as a life-hack, and now with the global coronavirus pandemic, Stoicism is a regular touchstone in prescriptions for maintaining sanity in troubled times. It’s not difficult to see why Stoicism is making a comeback. We’re facing difficult days, and the core insight of Stoic value theory is the grand division between what is up to us and what is not. Our mental life, what we think, to what we direct our attention, how we accept or reject ideas, and how we exercise our wills, are all up to us. And then there’s everything else: money, fame, health, status, and how things in the world generally go. If we attend only to the things in the first category (namely, that we maintain our cool, that we are critical thinkers, and we do our duty), then we will never be disappointed, because those are things up to us. But if we fixate on the latter things, then we are doomed to anxiety and disappointment, because those are things that are not up to us. Epictetus’ Enchiridion famously opens with this observation, and all Stoic ethics is driven by this intuitive distinction. However, a number of difficulties arise once one prescribes Stoicism as a coping strategy.

To start, there is what we’ve elsewhere called the “Stoicism for dark days problem.” Here it is in a nutshell. For Stoicism to do the work it promises as a coping strategy, we must not only practice Stoicism when things go badly, but also when things go well. You can’t turn Stoicism on when you need to weather dark days, since in order to do that you’d need to judge that things are going badly. But according to Stoicism, the only thing that could go badly (or well) is one’s exercise of judgment; thus, to exercise one’s judgment in light of an assessment that things are going badly is to commit an error that implicitly denies Stoicism. Instead, you need to be a Stoic during the good times, too. In his Meditations, Marcus Aurelius observes the problem of being double-minded between Stoic values and non-Stoic values when thinking about one’s life – he notes that it all too often results in confusion or incoherence (M 5.12). The trouble is that all of the attractions of Stoicism when it is offered as a consolation in trying times actually undercut the Stoic’s fundamental message. Read more »

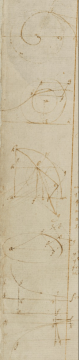

Annus Tranquillum

by Jonathan Kujawa

For mathematics, 1666 was the Annus Mirabilis (“wonderous year”). For the rest of humanity, it was pretty terrible. The plague once again burnt across Europe [1]. Cambridge University closed its doors and Issac Newton moved home.

Although only twenty-three years old, Newton was pretty well caught up to the state of the art in math and physics. Newton was brilliant, of course, but it also wasn’t so hard for an educated person to be at the cutting edge. After all, it was only thirty years earlier that Descartes and Fermat had introduced the notion of using letters (like x and y) for unknowns and had the insight that by plotting points on the xy-plane you could view algebra and geometry as two sides of the same coin.

With nothing better to do while quarantined at the family home, Newton settled back into the study of math and physics and, it turns out, ignited several world-changing revolutions in the process. Newton cracked open a 1000 page notebook he had inherited from his stepfather and got to work, recording his thoughts as he went. After reading Euclid’s Elements (still the gold standard after nearly 2,000 years!), Descartes, and the other books he had on hand, Newton began posing ever harder questions for himself which he then solved, inventing new math along the way.

Amazingly, Newton’s notebook (which he called his “Waste Book”) still exists! It is kept by the Cambridge University library along with thousands of pages of his other writings. In fact, you can read it for yourself online at the University’s website.

Some of the questions Newton posed could be considered standard, even for his day: computing roots, solving problems in geometry, and the like. Others are more open-ended: “If a Staffe bee bended to find the crooked line which it resembles.” or “To find such lines whose areas length or centers of gravity may bee found.”

In due course, Newton asks himself questions we recognize as the forerunners of calculus. Read more »

Kazuo Shiraga. Untitled 1964.

Kazuo Shiraga. Untitled 1964.