by Ashutosh Jogalekar

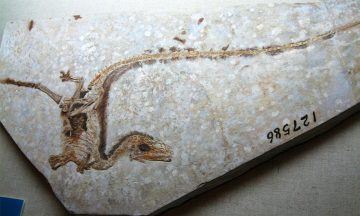

Neil Shubin’s “Some Assembly Required” is a delightful book whose thesis can be summarized in one word – “repurposing”. As Steve Jobs once put it, “Good artists create. Great artists steal”. By that reckoning Nature is undoubtedly the most magnificent thief and the greatest artist of all time. Repurposing in the history of life will undoubtedly become one of the great paradigms of science, and its discovery has not only provided immense insights into evolutionary biology but also promises to make key contributions to our understanding and treatment of human disease.

Among many other achievements of Darwin’s great theory was the explanation and prediction that similar parts of organisms had similar functions even if they might have looked different. One of the truly remarkable features of “On the Origin of Species” is how Darwin gets almost everything right, how even throwaway lines attest to a level of understanding of life that was solidified only decades after this death. The idea of repurposing came about in the “Origin” partly as a reply to objections raised by a man named St. George Jackson Mivart. Mivart was in the curious position of being a man of the cloth who had first wholeheartedly embraced Darwin’s theory and studied with Thomas Henry Huxley, Darwin’s most ardent champion, before then rejecting it and mounting an attack on it, timidly at first and then vociferously. Mivart’s own tract on the subject, “On the Genesis of Species” made his not-so-subtle dig at Darwin’s book clear.

Mivart’s basic objection was similar to that raised then and later by creationists. Darwin’s theory crucially relied on transitional forms that enabled major leaps in life’s history; from fish to amphibian for instance or from arboreal life to terrestrial life. But in Mivart’s view, any such major transition would involve not just a sudden change in one crucial body part, say from gills to lungs, but a change in multiple body parts. Clearly the transition from water to land for instance involved hundreds if not thousands of changes in organs and structures for locomotion, feeding and breathing. But how could all these changes arise out of thin air? How could gills for instance suddenly turn into lungs in the first lucky fish that crawled out of water and learnt how to survive on land? This problem according to Mivart was insurmountable and a fatal flaw in Darwin’s theory. Darwin took Mivart’s objections seriously enough to include a substantial section addressing them in the sixth and definitive edition of his book, first published in 1872. In it he acknowledged Mivart’s problems with his theory, and then did away with them succinctly: There is no problem imagining organs being used in different species, Darwin said, as long as they are “accompanied by a change in function.” In writing this Darwin was even further ahead of his time than he imagined. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Untitled; Arnold Arboretum, Boston, March, 2020.

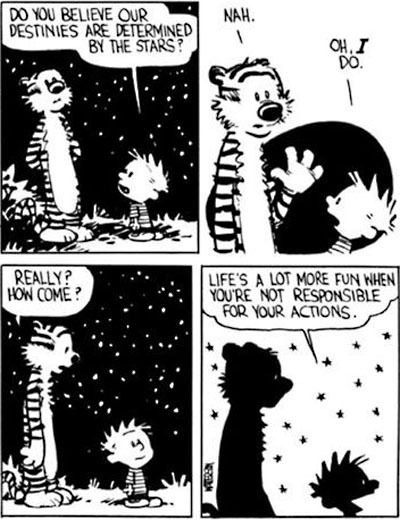

Sughra Raza. Untitled; Arnold Arboretum, Boston, March, 2020. The “Consequence Argument” is a powerful argument for the conclusion that, if determinism is true, then we have no control over what we do or will do. The argument is straightforward and simple (as given in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy):

The “Consequence Argument” is a powerful argument for the conclusion that, if determinism is true, then we have no control over what we do or will do. The argument is straightforward and simple (as given in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy): What can I make of these decisions emerging out of the blue, which I appear to act upon “freely?” What are the consequences of how I choose to react to them? Although these are vague philosophical musings, let’s look instead at the science of it all. I’m a layman, neither scientist nor philosopher, but as we are rediscovering, scientists are a less fuzzy lot than philosophers. I’m more likely to ask the woman with the medical degree about the true meaning of my dry cough than to ask philosopher

What can I make of these decisions emerging out of the blue, which I appear to act upon “freely?” What are the consequences of how I choose to react to them? Although these are vague philosophical musings, let’s look instead at the science of it all. I’m a layman, neither scientist nor philosopher, but as we are rediscovering, scientists are a less fuzzy lot than philosophers. I’m more likely to ask the woman with the medical degree about the true meaning of my dry cough than to ask philosopher

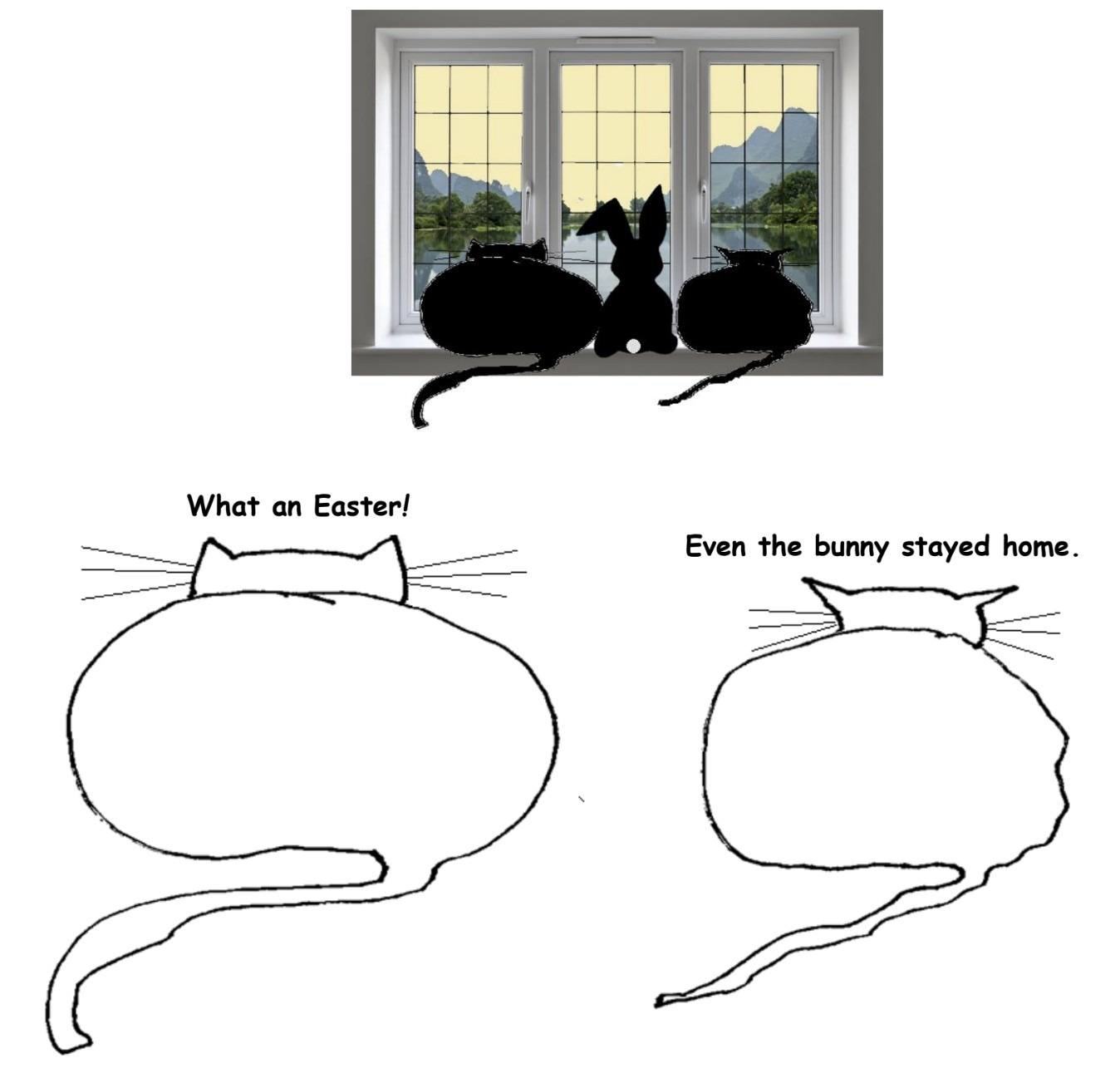

For the same reason as large parts of the world, I spend even more time indoors these days than I already would. One thing I have been doing is rereading the Harry Potter books – or paying Stephen Fry to read them to me.

For the same reason as large parts of the world, I spend even more time indoors these days than I already would. One thing I have been doing is rereading the Harry Potter books – or paying Stephen Fry to read them to me.

In the memoir, Running Toward Mystery: The Adventure of an Unconventional Life, the Venerable Tenzin Priyadarshi chooses to become a monk at the peak of his youthful potential. He rejects the spiritual path as a mere life enhancer and encourages readers to embark on a more totalizing journey of self-actualization. By embracing mystery, as opposed to cultural explanations, we can arrive at deeper questions. This wish bookends this carefully written memoir, which is co-authored by Zara Houshmand. Despite an already crowded landscape of books depicting religious quests and spiritual advice- both classics and new works – this book is bound to be widely read if for no other reason than Priyadarshi’s current role as a thought leader while serving as the first Buddhist chaplain at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

In the memoir, Running Toward Mystery: The Adventure of an Unconventional Life, the Venerable Tenzin Priyadarshi chooses to become a monk at the peak of his youthful potential. He rejects the spiritual path as a mere life enhancer and encourages readers to embark on a more totalizing journey of self-actualization. By embracing mystery, as opposed to cultural explanations, we can arrive at deeper questions. This wish bookends this carefully written memoir, which is co-authored by Zara Houshmand. Despite an already crowded landscape of books depicting religious quests and spiritual advice- both classics and new works – this book is bound to be widely read if for no other reason than Priyadarshi’s current role as a thought leader while serving as the first Buddhist chaplain at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Among other things Covid-19 is a moral crisis. It requires suspending the usual rules about who deserves what, firstly because it is impossible for many of us to pay what we owe in these conditions, and secondly because of the priority of the humanitarian duty to save as many lives as possible. Nevertheless we must not forget about justice. In particular we must make sure that the costs of this crisis are not born disproportionately by the poor, those least able to afford the burden but also least able to escape it.

Among other things Covid-19 is a moral crisis. It requires suspending the usual rules about who deserves what, firstly because it is impossible for many of us to pay what we owe in these conditions, and secondly because of the priority of the humanitarian duty to save as many lives as possible. Nevertheless we must not forget about justice. In particular we must make sure that the costs of this crisis are not born disproportionately by the poor, those least able to afford the burden but also least able to escape it.

The current Covid 19 pandemic is undoubtedly a disaster for millions of people: for those who die, who grieve for the dead, who suffer through a traumatic illness, or who, suddenly lacking work and income, face the prospect of dire poverty as the inevitable recession kicks in. And there are other bad consequences that one might not describe as ‘disastrous” but which are certainly significant: the stress experienced by all those providing care for the sick; the interruption in the education of students; the strain put on families holed up together perhaps for months on end; the loneliness suffered by those who are truly isolated; and the blighted career prospects of new graduates in both the public and the private sectors.

The current Covid 19 pandemic is undoubtedly a disaster for millions of people: for those who die, who grieve for the dead, who suffer through a traumatic illness, or who, suddenly lacking work and income, face the prospect of dire poverty as the inevitable recession kicks in. And there are other bad consequences that one might not describe as ‘disastrous” but which are certainly significant: the stress experienced by all those providing care for the sick; the interruption in the education of students; the strain put on families holed up together perhaps for months on end; the loneliness suffered by those who are truly isolated; and the blighted career prospects of new graduates in both the public and the private sectors.

The coronavirus amounts to an ongoing, real-world experiment in societal response to an international calamity. The pandemic will be studied for decades, but COVID has already taught us much about the relationship between science and decision-making.

The coronavirus amounts to an ongoing, real-world experiment in societal response to an international calamity. The pandemic will be studied for decades, but COVID has already taught us much about the relationship between science and decision-making. “Will we survive this?” my husband asks me as we lounge around the living room, glued to our laptops. “We are in the vulnerable group.” I look up at a bald man with thinning gray tufts over his ears, peering anxiously at me over black-rimmed glasses. Yes, we are certainly in the vulnerable group. What happened to that bright-eyed young man with fifteen pounds of black hair on his head, the one sporting sideburns that put Elvis to shame? Over his shoulder I see our son also looking expectantly at me, Camus’s The Plague in hand, open halfway.

“Will we survive this?” my husband asks me as we lounge around the living room, glued to our laptops. “We are in the vulnerable group.” I look up at a bald man with thinning gray tufts over his ears, peering anxiously at me over black-rimmed glasses. Yes, we are certainly in the vulnerable group. What happened to that bright-eyed young man with fifteen pounds of black hair on his head, the one sporting sideburns that put Elvis to shame? Over his shoulder I see our son also looking expectantly at me, Camus’s The Plague in hand, open halfway.