by Charlie Huenemann

“Every country is going through these decisions, none of us are through this pandemic yet, but some countries are starting to look at slightly expanding what people would define as their household — encouraging people who live alone to maybe match up with somebody else who is on their own or a couple of other people to have almost kind of bubbles of people,” she [Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon] told BBC Radio Scotland.

“Want to join my bubble? This is what your future social life could look like”, Angela Dewan, CNN, April 29th, 2020.

A crisis, by definition, has dramatic effects. It changes how we behave, where wealth goes, what policies we enact, and what we hope. But it also can bring into higher relief features of our lives that have not changed, but turn out to be more important than we realized.

Like the fact that human life takes place in bubbles. This just means that humans like to form groups: somewhat closed networks of interactive relationships among a small number of relatives or friends whose principal job it is to care for one another. “Semi-permeable palliative social matrices” one could call them, but “bubbles” will work just fine. A bubble is an enclosed space, protected from the outside by a fragile boundary; all its points are equidistant from a center; it is almost invisible, but offers a hopeful shine when the light hits it right. All the same can be said of a circle of good friends. And all of human history has been built upon such bubbles.

This crucial anthropological insight has been explored in nearly inexhaustible depth by the contemporary philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, particularly in his trilogy Spheres. Humans are born from round wombs into family circles, sometimes gathered in igloos and tipis, or around a hearth, following a circle of seasons under the orbs of moon and sun, growing into adulthood before they start the cycle again. Read more »

They’re quite a miracle, aren’t they, these phone calls, especially in these terrible times when one does not know what is going to happen to us, and to this country, this world. When we were in college in the U.S. in the late seventies, to talk to parents in Pakistan you had to book a call three weeks in advance. When your name came to the top of that line, you had to sit around the phone (there were no cell phones then) for ten hours. The call was expected to get through at any time during that window, for it had to be bounced over a satellite or some such complicated technological thing. What I recall most vividly about those moments is the excitement in the operator’s voice when the connection eventually happened. “Go ahead, ma’am/dear/hon,” they’d say, a triumphant edge to their tone, “your party is on the line.” I imagined the operator standing astride the Atlantic, a colossus holding the phone line up above her head out of the water just for the three minutes of my booked time so I could talk to my mother.

They’re quite a miracle, aren’t they, these phone calls, especially in these terrible times when one does not know what is going to happen to us, and to this country, this world. When we were in college in the U.S. in the late seventies, to talk to parents in Pakistan you had to book a call three weeks in advance. When your name came to the top of that line, you had to sit around the phone (there were no cell phones then) for ten hours. The call was expected to get through at any time during that window, for it had to be bounced over a satellite or some such complicated technological thing. What I recall most vividly about those moments is the excitement in the operator’s voice when the connection eventually happened. “Go ahead, ma’am/dear/hon,” they’d say, a triumphant edge to their tone, “your party is on the line.” I imagined the operator standing astride the Atlantic, a colossus holding the phone line up above her head out of the water just for the three minutes of my booked time so I could talk to my mother.

After several weeks of sheltering in place, being holed up in quarantine, or just experiencing a dramatically restricted mode of living due to the ongoing Covid 19 pandemic, it is quite natural to start feeling a little sorry for oneself. A wholesome remedy for such feelings is to think about other people who are also shut up, sometimes extremely isolated, and suffering much more serious kinds of deprivation. They do not have at their fingertips, thanks to the internet, an abundance of literature, music, film, drama, science, social science, news, sport, or funny cat videos. Nor are they casualties of fortune, shipwrecked and marooned by bad luck or the vicissitudes of market economies. Rather, they are the victims of deliberate and unjust oppression by authoritarian governments.

After several weeks of sheltering in place, being holed up in quarantine, or just experiencing a dramatically restricted mode of living due to the ongoing Covid 19 pandemic, it is quite natural to start feeling a little sorry for oneself. A wholesome remedy for such feelings is to think about other people who are also shut up, sometimes extremely isolated, and suffering much more serious kinds of deprivation. They do not have at their fingertips, thanks to the internet, an abundance of literature, music, film, drama, science, social science, news, sport, or funny cat videos. Nor are they casualties of fortune, shipwrecked and marooned by bad luck or the vicissitudes of market economies. Rather, they are the victims of deliberate and unjust oppression by authoritarian governments.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative.

In discourse about wine, we do not have a term that both denotes the highest quality level and indicates what that quality is that such wines possess. We often call wines “great”. But “great” refers to impact, not to the intrinsic qualities of the wine. Great wines are great because they are prestigious or highly successful—Screaming Eagle, Sassicaia, Chateau Margaux, Penfolds Grange, etc. They are made great by their celebrity, but the term doesn’t tell us what quality or qualities the wine exhibits in virtue of which they deserve their greatness. Sometimes the word “great” is just one among many generic terms—delicious, extraordinary, gorgeous, superb—we use to designate a wine that is really, really good. But these are vacuous, interchangeable and largely uninformative. Dedication

Dedication

Violence : War :: Lies : Mythology

Violence : War :: Lies : Mythology

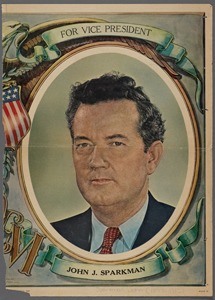

That Fifties-looking gent to your right is John J. Sparkman (D-Alabama) who was Adlai Stevenson’s running mate in 1952. Sparkman served in Congress for more than 40 years, the last 32 of them in the Senate. While not a star, he was associated with several pieces of important legislation and became Chair of the Senate Banking Committee and, late in his career, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He was also a committed segregationist and, in 1956, signed the Southern Manifesto, in emphatic opposition to Brown vs. Board of Education.

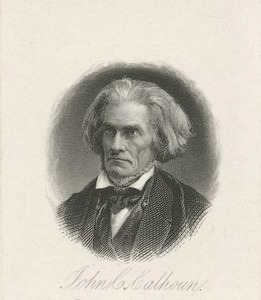

That Fifties-looking gent to your right is John J. Sparkman (D-Alabama) who was Adlai Stevenson’s running mate in 1952. Sparkman served in Congress for more than 40 years, the last 32 of them in the Senate. While not a star, he was associated with several pieces of important legislation and became Chair of the Senate Banking Committee and, late in his career, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He was also a committed segregationist and, in 1956, signed the Southern Manifesto, in emphatic opposition to Brown vs. Board of Education. This scary-looking guy to your left is John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who, during a truly extraordinary career that included being a Congressman, Senator, Secretary of State, and Secretary of War, also managed to sneak in two terms as Vice President under two very different Presidents, John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. You are going to hear a lot over the next few weeks about “chemistry” between Joe Biden and his running mate. Suffice it to say that John C. Calhoun never had chemistry with anyone, except perhaps of the combustible kind. Mr. Jackson and Mr. Calhoun disagreed constantly, particularly on the enforcement of federal laws that South Carolina found not to its liking (including the juicily named “Tariff of Abominations”), which led Mr. Calhoun to resign the Vice Presidency during the Nullification Crisis in 1832.

This scary-looking guy to your left is John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, who, during a truly extraordinary career that included being a Congressman, Senator, Secretary of State, and Secretary of War, also managed to sneak in two terms as Vice President under two very different Presidents, John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. You are going to hear a lot over the next few weeks about “chemistry” between Joe Biden and his running mate. Suffice it to say that John C. Calhoun never had chemistry with anyone, except perhaps of the combustible kind. Mr. Jackson and Mr. Calhoun disagreed constantly, particularly on the enforcement of federal laws that South Carolina found not to its liking (including the juicily named “Tariff of Abominations”), which led Mr. Calhoun to resign the Vice Presidency during the Nullification Crisis in 1832. They hauled us all in bas minis from the ranger station to the trailhead. From there, a six-kilometer trail led up to our destination, the Laban Ratah guest house, at 11,000 feet. At 13,432 feet, Mt. Kinabalu’s summit, in Malaysian Borneo, is the highest point in Southeast Asia.

They hauled us all in bas minis from the ranger station to the trailhead. From there, a six-kilometer trail led up to our destination, the Laban Ratah guest house, at 11,000 feet. At 13,432 feet, Mt. Kinabalu’s summit, in Malaysian Borneo, is the highest point in Southeast Asia.