by Akim Reinhardt

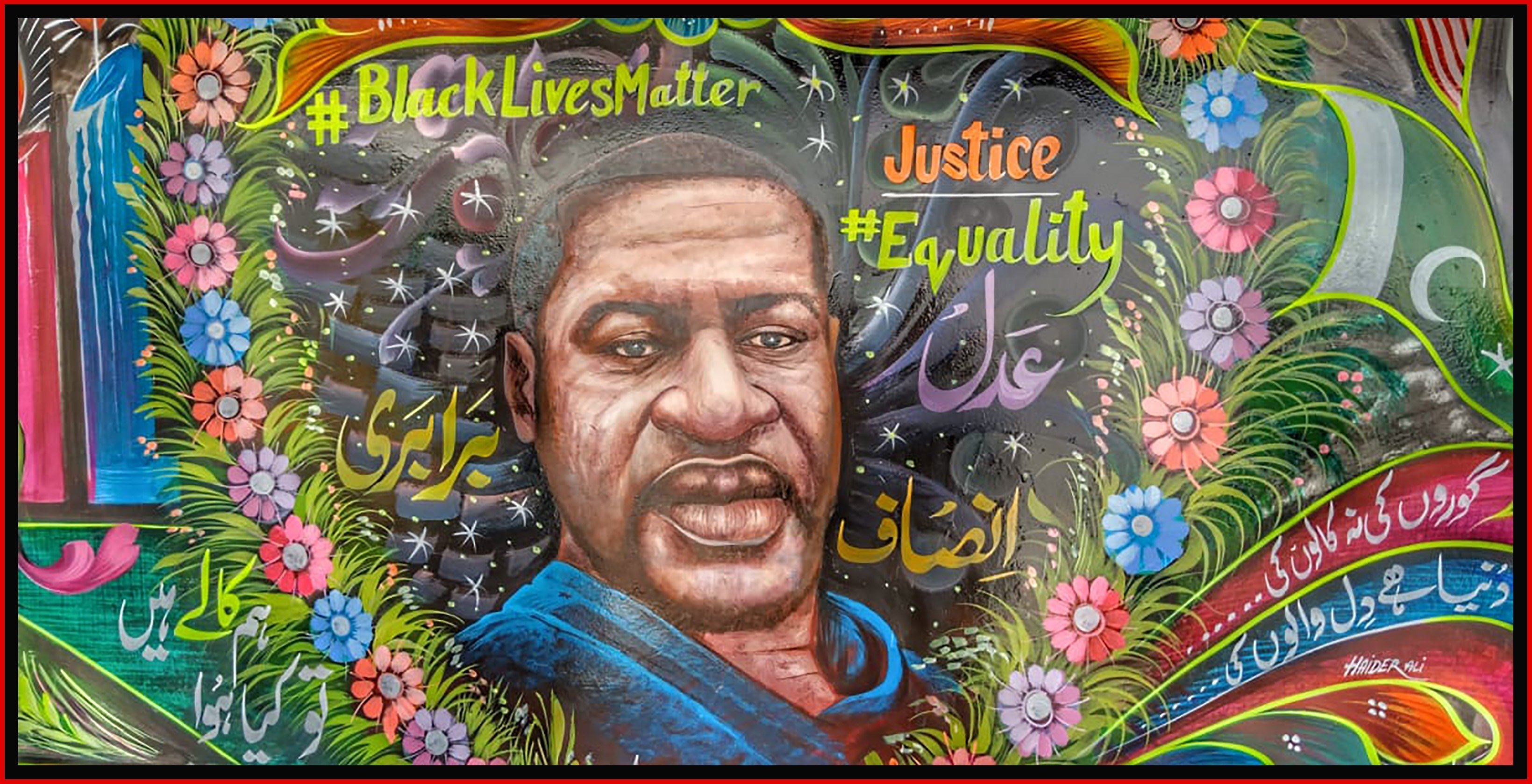

Two months ago, a college student in my Native American history class was perturbed. How it could be that during her K-12 education she never learned about the 1890 massacre of nearly 200 Native people at Wounded Knee? She was incensed and incredulous, and understandably so. It’s an important question, a frustrating question, and a depressing question. In other words, it’s the kind of question anyone who teaches Native American history is all too used to.

My students typically begin the semester with a vague sense of “we screwed over the Indians,” and are quickly stunned to discover the glaring depths of their own ignorance about the atrocities that Native peoples have endured: from enslavement, to massacres, to violent ethnic cleansings, to fraudulent U.S. government actions, to child theft and the forced sterilization of women, to a vast, far-reaching campaign of cultural genocide that continued unabated well into the 20th century.

I started slowly, explaining to her that one problem is the impossibility of covering everything in a high school history class. Even in a college survey, which moves much faster, you just can’t get to everything. There’s way too much. A high school curriculum has no chance.

But, I said, that begs the question, both for college and K-12: What gets in and what gets left out? Read more »

Had enough of the 2020 election? Take heart, there are just 134 days left until Vote-If-You-Can Tuesday. That’s less time than it took Napoleon to march his Grande Armée into Russia, win several lightning victories, stall out, and then retreat through the brutal winter, with astronomical casualties, all the while inspiring the equally long

Had enough of the 2020 election? Take heart, there are just 134 days left until Vote-If-You-Can Tuesday. That’s less time than it took Napoleon to march his Grande Armée into Russia, win several lightning victories, stall out, and then retreat through the brutal winter, with astronomical casualties, all the while inspiring the equally long

Last time

Last time Philosophy’s original contrarian hero was, of course, Socrates. He believed in Truth and the Good and refused to back down from the pursuit of the these – even when his life was on the line. He had no patience for ‘just whatever people tend to say about such and such’. The unexamined life, for him, was not worth living. And that examination requires being ready to question even your most cherished beliefs.

Philosophy’s original contrarian hero was, of course, Socrates. He believed in Truth and the Good and refused to back down from the pursuit of the these – even when his life was on the line. He had no patience for ‘just whatever people tend to say about such and such’. The unexamined life, for him, was not worth living. And that examination requires being ready to question even your most cherished beliefs. Some police officers are not above bad behavior, even as they work to eradicate and punish it in civilians. It is painfully clear that some of this bad behavior amounts to murder. Civilian review boards are a tool that could punish and deter police misconduct, but they need to have the ability to carry out independent investigations, subpoena documents and witnesses, and issue binding recommendations for discipline. As of a few years ago, only five of the top 50 largest police departments in the U.S. had civilian review boards with disciplinary authority. Newark, New Jersey has recently established such a review board after decades of efforts. While many activists have lost faith in civilian review boards, ACLU director of justice Udi Ofer argues that many of these boards were “rigged to fail.” He says a weak civilian review board is arguably worse than none at all, because it “can lead to an increase in community resentment, as residents go to the board to seek redress yet end up with little.”

Some police officers are not above bad behavior, even as they work to eradicate and punish it in civilians. It is painfully clear that some of this bad behavior amounts to murder. Civilian review boards are a tool that could punish and deter police misconduct, but they need to have the ability to carry out independent investigations, subpoena documents and witnesses, and issue binding recommendations for discipline. As of a few years ago, only five of the top 50 largest police departments in the U.S. had civilian review boards with disciplinary authority. Newark, New Jersey has recently established such a review board after decades of efforts. While many activists have lost faith in civilian review boards, ACLU director of justice Udi Ofer argues that many of these boards were “rigged to fail.” He says a weak civilian review board is arguably worse than none at all, because it “can lead to an increase in community resentment, as residents go to the board to seek redress yet end up with little.”

Now that we are witnessing a world that has withdrawn indoors, many people are reading plague literature, discussing Camus and Defoe, and reflecting on the nature of fear and contagion. But there is another kind of literature that lies neglected: stories that reflect the disconnect and dejection of seclusion -the literature of women’s isolation.

Now that we are witnessing a world that has withdrawn indoors, many people are reading plague literature, discussing Camus and Defoe, and reflecting on the nature of fear and contagion. But there is another kind of literature that lies neglected: stories that reflect the disconnect and dejection of seclusion -the literature of women’s isolation. When academics and journalists criticise technology today, they often assume the perspective of a bitter and desperate lover: intimately acquainted with the failings of technology, and vocal in pointing them out, but also too invested and unable to perceive the world without it.

When academics and journalists criticise technology today, they often assume the perspective of a bitter and desperate lover: intimately acquainted with the failings of technology, and vocal in pointing them out, but also too invested and unable to perceive the world without it.