by Mindy Clegg

In our modern society, we are awash in a near constant barrage of information. It can be difficult for even the most critically-minded among us to sift through all of that information and vet it for truthfulness. It’s likely that we all are subject to some misinformation that we believe in the course of our daily engagement with mass media. Although it’s more pervasive and immediate in today’s interconnected world, this state of affairs has existed since the beginning of the industrial age, starting with publishing in the nineteenth century and then onto broadcasting media of the twentieth century. But, if the medium is the message as Marshall McLuhan argued, what do these generations of engagement with mass forms of broadcasting actually mean for us as a society? The content fades away into the background to some degree while the medium shapes our shared experiences. Broadcasting and social media have become a shared prism on world, with differing interpretations of events experienced in a similar way.

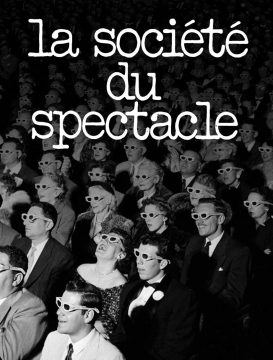

We rarely have public discussions on what a mass mediated society means for us, taking its existence for granted. Perhaps turning to a classic treatment of mass society might remind us of the historical and social constructedness of mass media. One such compelling work was the 1967 work by Situationist Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (published in English in 1970). Debord’s work has become a classic among philosophers, disaffected youth, and scholars attempting to come to grips with the role mass media plays in modern life. In this essay, I will argue that some of Debord’s assertions, such as his claim about the passivity encouraged by the spectacular industries, are incomplete. No form of mass medium was ever accepted passively. Rather, people as consumers often actively engaged with mass media, even if the goal was passive acceptance from the top down. I use the example of popular music to illustrate the point. Read more »

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose.

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose. Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Because I have a lot of experience with depression, I approached George Scialabba’s How to Be Depressed with an almost professional curiosity. Scialabba takes a creative approach to the depression memoir, blending personal essay, interview, and his own medical records, specifically, a selection of notes written by various therapists and psychiatrists who treated him for depression between 1970 and 2016. I don’t know if I could bear to see the records kept by those who have treated me for depression, assuming they still exist, and I wasn’t sure what it would be like to read another person’s medical history.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

by Paul Braterman

by Paul Braterman

John Lewis: Good Trouble

John Lewis: Good Trouble

The coronavirus pandemic has massively disrupted the working lives of millions of people. For those who have lost their jobs, income, or work-related benefits, this can mean serious hardship and anxiety. For others, it has meant getting used to new routines and methods of working. For all of us, though, it should prompt reflection on how we think about work in general–both as a curse and as a blessing. Here, I want to focus on how work relates to time.

The coronavirus pandemic has massively disrupted the working lives of millions of people. For those who have lost their jobs, income, or work-related benefits, this can mean serious hardship and anxiety. For others, it has meant getting used to new routines and methods of working. For all of us, though, it should prompt reflection on how we think about work in general–both as a curse and as a blessing. Here, I want to focus on how work relates to time. Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up.

Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up. In a survey released at the end of May by the AP and the NORC Center for public affairs research, 49% of Americans said they intended to be vaccinated against the new coronavirus, 31% said they were unsure, and 20% said they would not get the vaccine.

In a survey released at the end of May by the AP and the NORC Center for public affairs research, 49% of Americans said they intended to be vaccinated against the new coronavirus, 31% said they were unsure, and 20% said they would not get the vaccine.