by Sabyn Javeri Jillani

Now that we are witnessing a world that has withdrawn indoors, many people are reading plague literature, discussing Camus and Defoe, and reflecting on the nature of fear and contagion. But there is another kind of literature that lies neglected: stories that reflect the disconnect and dejection of seclusion -the literature of women’s isolation.

Now that we are witnessing a world that has withdrawn indoors, many people are reading plague literature, discussing Camus and Defoe, and reflecting on the nature of fear and contagion. But there is another kind of literature that lies neglected: stories that reflect the disconnect and dejection of seclusion -the literature of women’s isolation.

‘Alone today and for many days’, muses Virginia Woolf in her journal (1939) on the remoteness of wartime London. Today has a similar feel, as world over busy streets lie abandoned and silent, people cocooned in self-isolation. Those who are lucky enough, shelter in their sanctuaries, making seamless transitions to the digital world online. Those who are unable to adapt to this new reality, wait indoors for yesterday to return. Then, there are those for whom a house does not necessarily mean sanctuary, and yet others, who have no homes to shelter in. This pandemic has brought out many inequalities and injustices in our world but the one that seems overlooked is that self-isolation is not something new — for women.

There is, of course, the idea of a room of one’s own, which may empower a woman’s creative genius. But it is not Woolf’s idea of solitude that I discuss here but of isolation. An isolation that is linked to quarantine, and the idea of contagion. In many traditional societies, self-isolation is forced upon women as a custom during certain periods of their life such as menstruation (Chhaupadi), childbirth (Zuo yue zi), widowhood or, at times, even divorce (Iddat/Iddah). Through superstition or ritual, they are quarantined.

Today, psychologists are discussing the effects of self-isolation on our mental health and there is much research linking it to depression and low self-esteem. Yet, there is little connection with women who have been put through this self-isolation practice, whether in private spaces or in public, as in the recent case of the Sabrimala temple in Kerala where a women’s rights group protested for the right of women of menstruating age to enter. For many, this may well be the first introduction to the gender inequalities in cultures that force women to isolate, but it is not just a matter of measuring women’s rights in the global South through the lens of the global North. The issue here is a culture of shame and impurity divided by binaries which women are often unable to challenge; therefore, they internalize it, no matter which part of the world they are in.

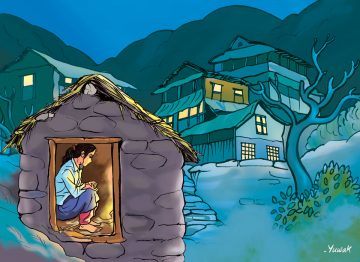

Menstruation is one such state that has long been linked with impurity and contagion. In many cultures and religions women are not allowed to pray, touch, or enter a sacred space for fear that they will defile it with their presence. The intensity of observing the ritual depends on the orthodoxy. Some cultures even fear that food may become contaminated by the touch of a menstruating woman and therefore quarantine them. Chhaupadi is one such practice where menstruating women are coerced into self-isolation during mensuration so as not to ‘defile’ anything with their presence. ‘Chhaupadi comes from Nepali words that mean someone who bears an impurity, and it has been going on for hundreds of years, reported the New York Times. In 2018, the Nepali government formed a law against forcing a menstruating woman into seclusion, punishable by up to three months in jail. Sadly, though it created some awareness on a global level, the practice continues in many places and, each year, women die because of it. In March 2017, the National Geographic reported about the ‘extreme situations women in rural regions (Nepal) endure for one week each month over the 35-45 years of their menstrual cycle. Viewed as unclean, untouchable, and having the power to bestow calamity upon people, livestock, and the land when bleeding, women are banished from their homes. Some stay in nearby sheds, while others must travel 10-15 minutes away from home on foot through thick forests to small secluded huts. While banished, the women face — and frequently die from — brutally hot temperatures, asphyxiation from fires lit to keep warm during winter, the venom of cobra snakes, and rape.’ While the deaths and assault chock up statistics, they do little to deter this practice, and the mental health effects of the rituals are rarely accounted for or discussed.

In Judaism the feminine noun niddah means moved (i.e. separated), generally refers to separation due to ritual impurity. Bapsi Sidhwa describes this practice of seclusion in a Parsi household in her novel, The Crow Eaters (1992), where a female character, ‘Putli’, is similarly banished to the store during her ‘days’, as mensuration is often referred to in the subcontinent. Bapsi writes: ‘Every Parsee household has its other room, specially reserved for women. Thither they are banished for the duration of their unholy state. Even the sun, moon and stars are defiled by her impure gaze, according to a superstition that has its source in primitive man’s fear of blood… She left the room only to use the bathroom. Then she would loudly proclaim her intention and call, “I am coming. I want to pass urine”, or, as the case might be, “I want to wash”. In either case, if Jerbanoo or Freddy were at the prayer table, they anxiously shouted, “Wait!” Hastily finishing their prayers, they scurried out of the room and called back. “All right, you can come now.” Once the all-clear was sounded, Putli made a beeline for the bathroom, carefully shading her face with a shawl from the prayer table. She was served meals in her cubicle. A tin plate and spoon, reserved for the occasion, were handed over by the servant boy. She knew she couldn’t help herself to pickles or preserves for they would spoil at her touch. Flowers, too, were known to wilt when touched by women in her condition. The family was permitted to speak to her through closed doors — in an emergency, they could speak directly, provided they bathed from head to foot and purified themselves afterwards.’ (p.66)

Though set in pre-partition India, and no longer widely practiced in the Parsi community, Putli’s portrayal may be all too familiar to women who grow up in orthodox households which still follow this practice. And it makes one wonder if social distancing and self-isolation during a pandemic can lead to depression, the fear of isolation in an unfamiliar and uncomfortable space, crippled with the shame of menstruation, must surely lead to even more problematic mental health issues. However, there is little discussion on this as often the ritual is presented as a relief to women from their duties. Sidhwa, too, follows up this description of Putli’s seclusion as a moment of respite. ‘It was the only chance she ever had to rest,’ Sidhwa writes. ‘And since this seclusion was religiously enforced, she was able to enjoy her idleness without guilt.’(p. 67).

Patriarchal practices such as sati and honor killing are often rationalized as moral. The idea of contagion or impurity is often guised in a manner that ends up with women internalizing and even endorsing such practices, as can be seen in the case of the Sabrimala temple where many women refused to enter, even when they were granted the right to do so and preferred, instead, to practice ‘tradition’. Similarly, many women still justify Chhaupadi as a chance to relax, but can one justify the shame of seclusion for being unable to control the secretions from one’s body during mensuration as something welcoming and not isolating? Or the fact that the only way they can get a break from their chores is through quarantine, much in the manner of slavery? Even if one was to practice it voluntarily, how does such a practice of isolation affect the mental wellbeing of women? What effect does it have on their self-esteem? On their relationship with their bodies? It is disturbing to know that in all the recent talk about self-isolation, hardly any reference has been made to women who have been subjected to ritualistic seclusion for decades. There are cultures that still subscribe to this view as can be seen in the laws being formulated in Nepal or India. Although women may not be put into complete isolation in other societies, they are still banned in many religions from performing certain acts such as touching an object of religious significance, entering a mosque or temple, or cooking a male member’s food. The idea of contagion is rampant.

The practice of self-isolation which starts at the onset of adolescence carries on in childbirth too. Zuo yue zi, or ‘sitting the month’ as it is known in China, is practiced across many cultures. The fact that until a few decades ago pregnancy itself was referred to as confinement, which by default implies imprisonment, shows how isolating an experience this can be. Like menstruation, postpartum confinement is also treated as a time to rest. Though, like menstruation, it may well be the Lochia discharge that continues after birth for about 4 or so weeks, and it’s association with contamination, that could be the reasoning behind it. However, the idea of spending 30 to 40 days indoors after giving birth is often channeled as a way of observing quarantine until a newborn is strong enough to form immunity. How isolating must this be for a new mother. And why is there such little research about the mental state of the self-isolating mothers despite it being linked to postpartum depression? And more importantly, why does the practice continue in present day when vaccinations are widely available? In 2017, the BBC did a piece on postnatal confinement titled ‘Why British Chinese mothers won’t go out after giving birth’, at women from British- Chinese and Asian communities who still practiced it. The report quotes a medical expert, Dr Wu, on the effect confinement has on some British Chinese mothers who experienced postnatal depression. “New mums can often be left in isolation and it can be difficult to cope,” she says. What is left unsaid, is how a custom that shames women for their natural state is often endorsed as ritual.

There seems to be a pattern of contamination here that highlights the septicity associated with women. The way isolation is linked with a woman’s fertility seems almost dehumanizing: isolated during menstruation, confined when pregnant and again after giving birth, and then carried on to the next stage of seclusion during widowhood or divorce by observing Iddah — a 40- to 90-day period of self-isolation, practiced in many Islamic societies. Again, explained by elders as a woman’s time to mourn, one wonders how being banished indoors from everyday life for such a length of time can lead to healing instead of depression. In theological discussions, it is reasoned that this seclusion is necessary to prevent the immediate remarrying of women so that it can be ascertained that they are not pregnant, as this may lead to paternity confusion. The logic and its pre-logic both seem problematic as they strip the woman of the choice to make her own decisions. And, as is often the case, literature portrays this powerlessness much more clearly than scripture or scholarship does. In her novel, So Long a Letter (1989), Senegalese author Mariama Ba paints a powerful portrayal of the mental and physical cost of isolation through her protagonist — a middleclass Muslim widow observing Iddah. Confined indoors during her Iddah period, the narrator recalls her life in a letter she writes to a childhood friend. There is one line in the novel which sums up her frustration; recalling the happy memories which became painful when her identity as a woman is reduced to that of a wife and then of a widow, she writes, ‘I know that I am shaking you, that I am twisting a knife in a wound hardly healed; but what can I do? I cannot help remembering in my forced solitude and reclusion.’ Her grief and loneliness during the Iddah period magnifies when she is confined indoors with little to distract her. In a haunting portrayal of withdrawal from the outside world, Ba describes how the widow begins to see herself almost like a tangible object whose value can be measured only in terms of re-marriage. Again, the narrative touches upon the idea of contagion, the bad luck of the widow which may rub off on others, her freedom from quarantine dependent on her marriageability, and the enforced isolation that reduces women to objects and not subjects of their own lives.

Literature has long provided a space for conversations which history has swept under the carpet. And the loneliness of women forced into an artificial quarantine is a topic that has once again escaped the notice of many ‘experts’ while they discuss the impact of self-isolation during Covid-19. There is concern for those who do not feel safe in their homes because of domestic violence and abuse, and some governments have even launched schemes such as mask19 to protect the vulnerable. But what of those for whom these equally violent practices of isolation are legitimized and normalized as a way of life? What of those women whose natural state of being is associated with contagion at certain stages in their life? To forget them is to see our vulnerability reflected in the global isolation that Covid-19 has caused. To remember them is to realize that we cannot maintain these disturbing distinctions between cultural practices and inhumanity, something that the tradition of women’s writing reminds us of. Joanna Russ writes in How to Suppress Women’s Writing (1983), ‘Ignorance is not bad faith. But persistence in ignorance is’.

***

Sabyn Javeri – Jillani is the author of Hijabistan (Harper Collins, 2019) and the novel Nobody Killed Her (Harper Collins, 2017). She teaches literature, and writing at New York University, Abu Dhabi.