by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

Gems carry a lure that is quintessentially primeval. Considered valuable throughout human history for obvious reasons such as rarity, durability and beauty, gems are inextricable not only from lore, art, architecture, culture, and craft, but also the aesthetics of language. Stories of different civilizations come to us carved in gemstones— Jade figurines of the Forbidden City in Beijing, lapis funerary masks of ancient Egypt, amber encrusted palaces in Moscow, the fabled and famously fought over “koh-i-noor” diamond, the emerald cups and diamond candlesticks of the Ottomans, the bejeweled “peacock throne,” the rubies of Ceylon— and stories manifold to these in words, from myths passed down via the oral tradition, to scripture, fairy tales, poetry and actual accounts of history, to science talk of archeology and gemology.

Gems carry a lure that is quintessentially primeval. Considered valuable throughout human history for obvious reasons such as rarity, durability and beauty, gems are inextricable not only from lore, art, architecture, culture, and craft, but also the aesthetics of language. Stories of different civilizations come to us carved in gemstones— Jade figurines of the Forbidden City in Beijing, lapis funerary masks of ancient Egypt, amber encrusted palaces in Moscow, the fabled and famously fought over “koh-i-noor” diamond, the emerald cups and diamond candlesticks of the Ottomans, the bejeweled “peacock throne,” the rubies of Ceylon— and stories manifold to these in words, from myths passed down via the oral tradition, to scripture, fairy tales, poetry and actual accounts of history, to science talk of archeology and gemology.

The seventeenth century Flemish chronicler and diamond dealer Jacques de Coutre describes the Mughal emperor Jahangir as “looking like an idol on account of the quantities of jewels he wore, with many precious stones around his neck as well as spinels, emeralds and pearls on his arms, and diamonds hanging from his turban.” While some are attracted to gems as symbols of power and wealth, and others as the source of wellness energy, adornment or materials for craft, poets, artisans and artists have developed a complex vocabulary around gems through the millennia and across cultures. Vermeer brings out the unique luster of a pearl, in “The Girl with the pearl Earring,” the mosque-builders of Samarkand make an epic out of turquoise, Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato uses the most precious pigment available— derived from lapis lazuli— to paint the richest, most vibrant blue mantle in “The Virgin in Prayer,” the Mughals build the Taj Mahal, an architectural marvel of gem-inlay and marble. Read more »

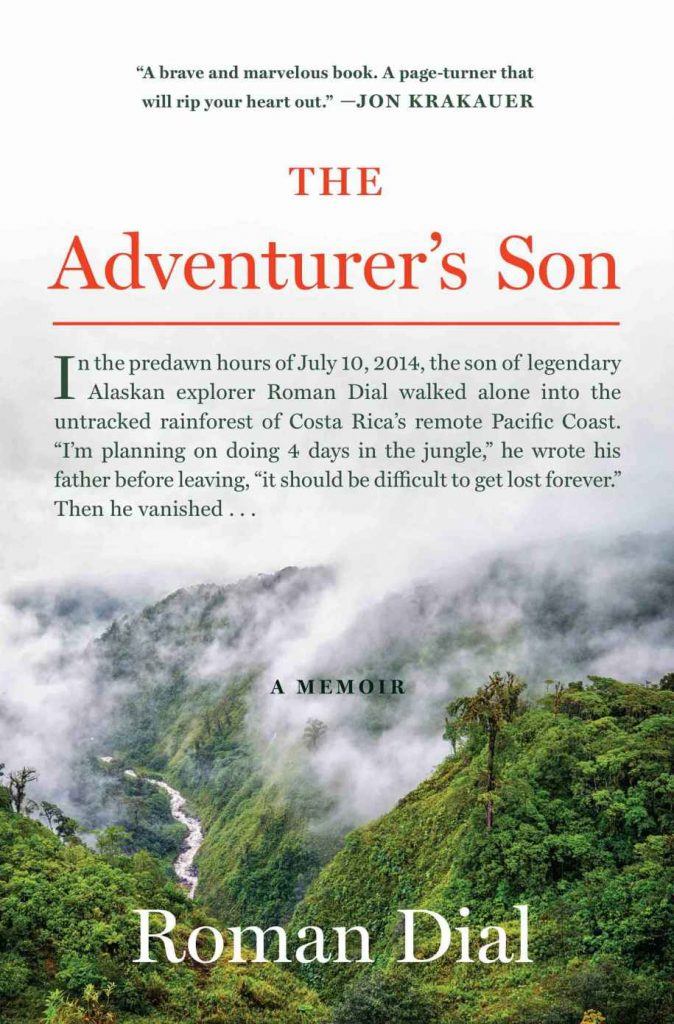

Roman Dial has written a great tribute to his son, indeed to his entire family, in his book The Adventurer’s Son. An adventurer and biologist, Dial writes movingly of his relationship with his only son, Cody Roman Dial in particular and of his accidental death while exploring the rainforests of Central America. Dial’s pride in his son and the pain and grief over his loss are palpable throughout the book. But as Dial himself acknowledges, ‘we never know the future’, and the death of his son at just 27 years old in 2014 is an event he could never have imagined when he began to introduce him to the joys and challenges of exploring the natural world.

Roman Dial has written a great tribute to his son, indeed to his entire family, in his book The Adventurer’s Son. An adventurer and biologist, Dial writes movingly of his relationship with his only son, Cody Roman Dial in particular and of his accidental death while exploring the rainforests of Central America. Dial’s pride in his son and the pain and grief over his loss are palpable throughout the book. But as Dial himself acknowledges, ‘we never know the future’, and the death of his son at just 27 years old in 2014 is an event he could never have imagined when he began to introduce him to the joys and challenges of exploring the natural world. In coping with the dire economic crisis in the wake of the pandemic many developing countries have resorted to cash assistance to the poor for immediate relief. Beyond the relief aspect, many macro-economists have also pointed to the need for such programs to boost mass consumer demand in a period of one of the deepest slumps of general economic activity in many decades. As I have been an advocate for universal basic income (UBI) in poor countries for more than a decade now—my first published paper on the subject came out in India in March 2011 in the Economic and Political Weekly— I have often been asked if the widespread adoption of such cash assistance programs indicates that it is now a propitious time for UBI. While I have supported the cash relief programs in the context of the crisis (most of these programs have not been universal, mainly targeted to the poor) and consider the experience gained in this as generally useful, I think those who like me have supported UBI have usually thought about it in a longer-time framework and in the context of a more ‘normal’ state of the economy with appropriate institutions, political support base, and administrative structures in place. Of course, I’ll not object if in a post-pandemic world attempts are made to help the temporary crisis programs ultimately extend or evolve into a more general UBI program in poor countries.

In coping with the dire economic crisis in the wake of the pandemic many developing countries have resorted to cash assistance to the poor for immediate relief. Beyond the relief aspect, many macro-economists have also pointed to the need for such programs to boost mass consumer demand in a period of one of the deepest slumps of general economic activity in many decades. As I have been an advocate for universal basic income (UBI) in poor countries for more than a decade now—my first published paper on the subject came out in India in March 2011 in the Economic and Political Weekly— I have often been asked if the widespread adoption of such cash assistance programs indicates that it is now a propitious time for UBI. While I have supported the cash relief programs in the context of the crisis (most of these programs have not been universal, mainly targeted to the poor) and consider the experience gained in this as generally useful, I think those who like me have supported UBI have usually thought about it in a longer-time framework and in the context of a more ‘normal’ state of the economy with appropriate institutions, political support base, and administrative structures in place. Of course, I’ll not object if in a post-pandemic world attempts are made to help the temporary crisis programs ultimately extend or evolve into a more general UBI program in poor countries. What does it mean to be white in America in 2020?

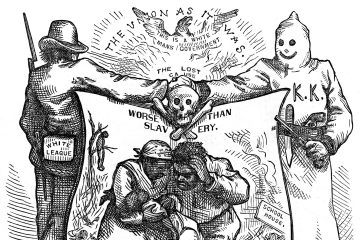

What does it mean to be white in America in 2020?

May 26, 2020

May 26, 2020

Have a look at the

Have a look at the  In thinking about knowledge and consciousness, it is just about irresistible to distinguish between the basic facts of what we observe and interpretations or beliefs about those facts. You and I see the same glass of water – maybe our perceptions of the glass are nearly identical – and yet you see it has half full while I see it as half empty. We look at the same economic reports, and you find reason to celebrate while I find cause to worry. We see an artificial satellite in orbit, and you see it an incursion of government and industry into space while I see it as a glory of science and engineering. And so on – it seems obvious that there is a divide between what everyone can plainly see and what’s a matter of interpretation.

In thinking about knowledge and consciousness, it is just about irresistible to distinguish between the basic facts of what we observe and interpretations or beliefs about those facts. You and I see the same glass of water – maybe our perceptions of the glass are nearly identical – and yet you see it has half full while I see it as half empty. We look at the same economic reports, and you find reason to celebrate while I find cause to worry. We see an artificial satellite in orbit, and you see it an incursion of government and industry into space while I see it as a glory of science and engineering. And so on – it seems obvious that there is a divide between what everyone can plainly see and what’s a matter of interpretation.

When I feel myself becoming irritable, disheartened, or just plain fed-up with life during the pandemic, I find it helpful to conduct a thought-experiment familiar to the ancient Stoics. I reflect on how much I have to be grateful for, and how things could be so much worse. That prompts the more general question: Who are the fortunate, and who are the unfortunate at this time?

When I feel myself becoming irritable, disheartened, or just plain fed-up with life during the pandemic, I find it helpful to conduct a thought-experiment familiar to the ancient Stoics. I reflect on how much I have to be grateful for, and how things could be so much worse. That prompts the more general question: Who are the fortunate, and who are the unfortunate at this time?

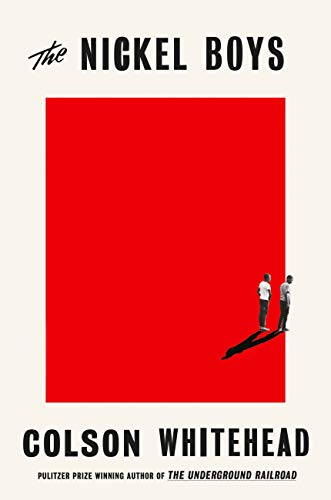

Colson Whitehead won his second Pulitzer Prize for The Nickel Boys in 2020, joining the ranks of three other writers recognized for the rare honor. His first was for another historical fiction The Underground Railroad in 2017. What are the odds of winning the Pulitzer for two books that deal with the same subject – the troubled race relations in America? Pretty good, I would say, if your second book is as brilliant as The Nickel Boys.

Colson Whitehead won his second Pulitzer Prize for The Nickel Boys in 2020, joining the ranks of three other writers recognized for the rare honor. His first was for another historical fiction The Underground Railroad in 2017. What are the odds of winning the Pulitzer for two books that deal with the same subject – the troubled race relations in America? Pretty good, I would say, if your second book is as brilliant as The Nickel Boys.