by Eric J. Weiner

White people go around, it seems to me, with a very carefully suppressed terror of Black people—a tremendous uneasiness. They don’t know what the Black face hides. They’re sure it’s hiding something. What it’s hiding is American history. What it’s hiding is what white people know they have done, and what they like doing. White people know very well one thing; it’s the only thing they have to know. They know this; everything else, they’ll say, is a lie. They know they would not like to be Black here. They know that, and they’re telling me lies. They’re telling me and my children nothing but lies. —James Baldwin, 1979

What and how the Nation teaches its children says a lot about the political principles for which it stands. Through a complex mechanics of curriculum, pedagogy, assessment, discourse, and discipline, public school systems have always operated as cultural and ideological state apparatuses. This means that they help to reproduce the dominant ideological and cultural logic of the nation-state of which they are an integral part. The mechanics of public education change as the ideological and cultural morphology of the state changes. Yet, schools are also sites of struggle over the Nation’s dominant ideological and cultural interests. As Henry Giroux has shown, there is always resistance at the curricular, pedagogical, and discursive levels to the reproductive energies of the state. Teachers, students, parents, and other stake-holders are always, from one side of the ideological spectrum to the other, pushing back against the reproductive mechanics of the school. One articulation of resistance that has become a source of outrage and concern in our current times for many liberals and conservatives is the move by some states, districts and schools to use Critical Race Theory (CRT) to reframe what and how American history is taught.

CRT, explains Stephen Sawchuk, Associate Editor of Education Week, “is an academic concept that is more than 40 years old. The core idea is that racism is a social construct, and that it is not merely the product of individual bias or prejudice, but also something embedded in legal systems and policies.” Within the context of schooling, CRT researchers and scholars “look at how policies and practices in K-12 education contribute to persistent racial inequalities in education, and advocate for ways to change them.” Researchers working within the framework of CRT over the past 40 years have shown, qualitatively and quantitatively, how systemic racism in the areas of housing, finance, law, healthcare, and education has disenfranchised, marginalized, oppressed, and dehumanized people of color from the Nation’s inception and continue today. Read more »

When we were young, most of us indulged in the speculation, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” Many of us said things like a firefighter, a doctor, a nurse, or a teacher. As children, we instinctively looked at the world around us and recognized the careers that seemed to have purpose and meaning, and that seemed to make the world a better place. I can’t imagine that many 5-years olds dreamed of being paper pushers or spending their days doing data entry. But we grow up. People around us have expectations for us; we have expectations for ourselves. We might have academic challenges, financial needs, family obligations. We see the world and the careers open to us as more diverse and as more challenging than the Fisher-Price Little People figures that characterize the world for a child. And so, many of us lose that childhood idealism and just get a job, get on the career ladder, put our noses to the grindstone.

When we were young, most of us indulged in the speculation, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” Many of us said things like a firefighter, a doctor, a nurse, or a teacher. As children, we instinctively looked at the world around us and recognized the careers that seemed to have purpose and meaning, and that seemed to make the world a better place. I can’t imagine that many 5-years olds dreamed of being paper pushers or spending their days doing data entry. But we grow up. People around us have expectations for us; we have expectations for ourselves. We might have academic challenges, financial needs, family obligations. We see the world and the careers open to us as more diverse and as more challenging than the Fisher-Price Little People figures that characterize the world for a child. And so, many of us lose that childhood idealism and just get a job, get on the career ladder, put our noses to the grindstone. The desire to turn failure into a learning opportunity is often generous, and an important way of dealing with the trials and tribulations of life. I first became aware of it as a frequent trope in start-up culture, where, influenced by practices in software development where trying things out and failing is the quickest way to get to something of value, we are constantly subject to exhortations to “fail fast and fail forward”. Many workplaces now lionise (whether sincerely or not is another matter) the importance of learning through failure, and of creating environments that encourage this.

The desire to turn failure into a learning opportunity is often generous, and an important way of dealing with the trials and tribulations of life. I first became aware of it as a frequent trope in start-up culture, where, influenced by practices in software development where trying things out and failing is the quickest way to get to something of value, we are constantly subject to exhortations to “fail fast and fail forward”. Many workplaces now lionise (whether sincerely or not is another matter) the importance of learning through failure, and of creating environments that encourage this.

If you’d like to start at the beginning, read

If you’d like to start at the beginning, read

‘

‘ In

In

Jean Shin. Fallen. Installation at Olana State Historic Site, New York.

Jean Shin. Fallen. Installation at Olana State Historic Site, New York.

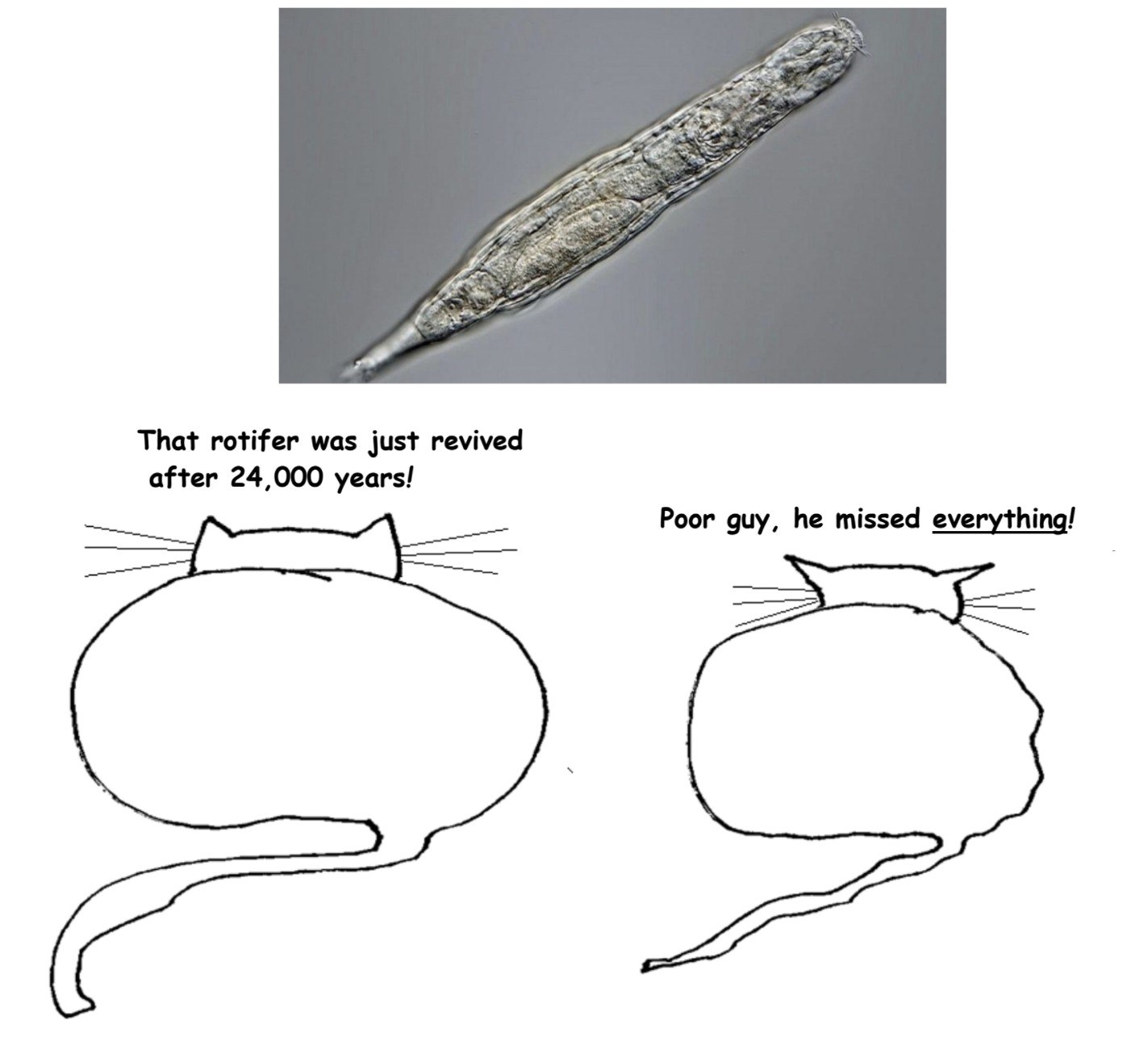

Time isn’t what it used to be. The pandemic has altered our perception of it. This is why time is no longer quite as valuable as it was before we were suddenly assaulted with too much of it. It used to be a commodity in short supply. It’s even been called a currency (time is money), but the reverse was never true. No matter how many billions Mr. Bezos has, he has no more hours in his day than I do.

Time isn’t what it used to be. The pandemic has altered our perception of it. This is why time is no longer quite as valuable as it was before we were suddenly assaulted with too much of it. It used to be a commodity in short supply. It’s even been called a currency (time is money), but the reverse was never true. No matter how many billions Mr. Bezos has, he has no more hours in his day than I do. The evidence that mass media can cause physiological responses in humans is so evident in our everyday experience that it’s easy to ignore. Subliminal muzak makes our fingers tap lightly on our grocery carts. Billboards with sexy models flush our cheeks during our daily commutes. But not all such stimuli are subtle. For those media products whose main purpose is to cause a physiological response, genre labels serve as warnings—e.g., we label items that make us laugh as comedy, items that turn us on as pornography, or items that trigger our fight-or-flight response as horror. Modern people have complex attitudes toward media that invoke a physiological response, and practitioners of such genres alternatively experience intense celebration and intense censure.

The evidence that mass media can cause physiological responses in humans is so evident in our everyday experience that it’s easy to ignore. Subliminal muzak makes our fingers tap lightly on our grocery carts. Billboards with sexy models flush our cheeks during our daily commutes. But not all such stimuli are subtle. For those media products whose main purpose is to cause a physiological response, genre labels serve as warnings—e.g., we label items that make us laugh as comedy, items that turn us on as pornography, or items that trigger our fight-or-flight response as horror. Modern people have complex attitudes toward media that invoke a physiological response, and practitioners of such genres alternatively experience intense celebration and intense censure.