Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. The Prologue is here. The table of contents with links to previous chapters is here.

by Akim Reinhardt

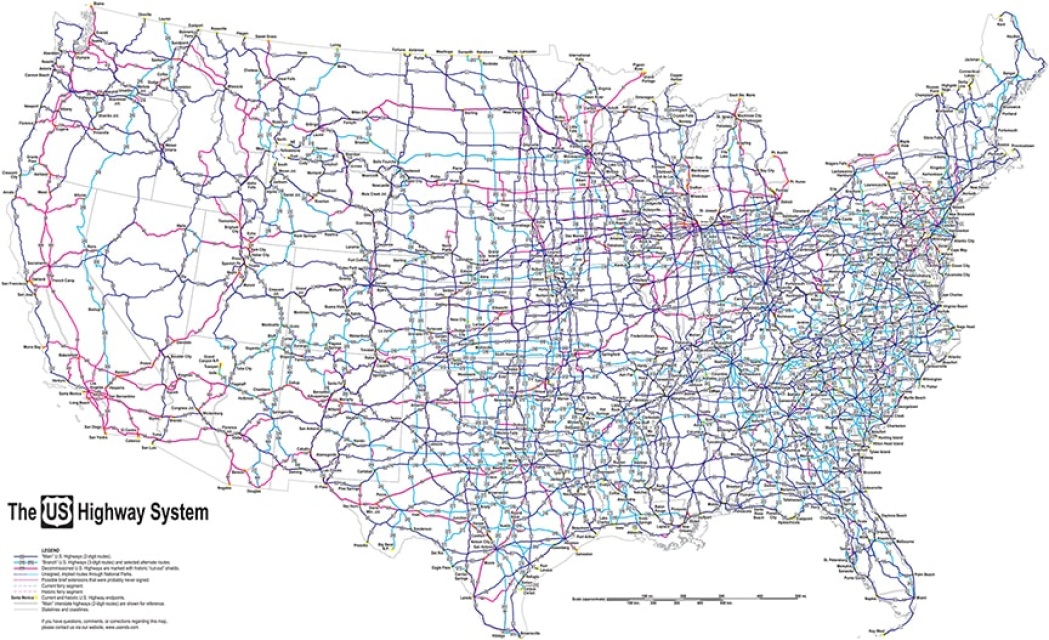

This song got caught in my head as I circled the country in my 1998 Honda. Leaving New York City, I drove west into the heart of America, up to the Dakotas, out to California, down the Golden State, and then back along the Southern route before angling northward to Baltimore. I saw nearly all the America you can see. But of course there’s not just one America. There are many.

This song got caught in my head as I circled the country in my 1998 Honda. Leaving New York City, I drove west into the heart of America, up to the Dakotas, out to California, down the Golden State, and then back along the Southern route before angling northward to Baltimore. I saw nearly all the America you can see. But of course there’s not just one America. There are many.

The environment shifts dramatically along the way. So too do the people. From densely packed cities to sparsely populated rural areas. From little towns dotting the countryside to sprawling suburbs that fade into forest or desert or grasslands. It is a vast expanse, the world’s third largest nation in both square mileage (behind Russia and Canada) and population (behind China and India). When I was a kid there were 200,000,000 people. Or so a Burger King commercial told us. Now we’re closing in on 350,000,000.

It takes all types. But of course some types get more attention than others. Mass media consistently highlight white people, the major exception being black entertainers (mostly athletes and singers) and criminals. Men continue to dominate positions of power and prestige. The coasts boast most of the population, and sneeringly refer to the middle as “fly over country.” And the cities and suburbs, home to the vast majority of Americans, largely ignore the small towns and rural areas that actually makeup most of the physical landscape.

My own life illustrates many of America’s different faces. Read more »