by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

Ami, my mother, does my hair, “Helen-of-Troy-style,” a high pony tail with strands wrapped around it on days there is extra time before school. She remembers the hairdo from an old movie which she talks about often, along with her other favorite The Taming of the Shrew with Liz Taylor. When she combs, she hums, mostly Urdu songs, occasionally Punjabi. Since settling in Peshawar, she has taught herself Pashto not only because it isn’t easy to run a household and her myriad projects without knowing the local language, but because she has a genuine love for connecting with people of all kinds, everywhere. We joke that she can make friends while crossing the road; this is something she and I don’t have in common. I tend to be withdrawn, like my father, content with my books and thoughts.

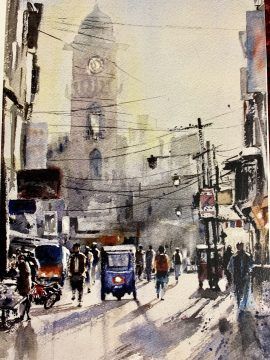

There are times when I do enjoy going on outings, especially when Ami takes me on an excursion to the old city and shows me how herbs, spices, henna, tealeaves, and grains of every kind are sold box-less, displayed in smooth mounds. I like to walk through the narrow streets with her, taking in the crisp, salty aroma of street food, the colors of sherbets, glass bangles, sparkly trim for dupattas, watching shopkeepers with their paraphernalia— their weighing scales, aluminum scoops and glossy brown paper bags. The joy of walking through a bazar, which will become a subject I’ll explore for years in my writing, begins here. I feel certain that if I were to put my ear to the ground, I’ll hear the tread of Silk Road caravans. My curiosity about how cultures of encounter are formed and revealed in the marketplace— about trade- and work habits, competition and conflict, creative marketing, the ethos of fair-play and equality and the complex dynamics of cosmopolitanism— is born as a result of watching my mother interact. I’m astonished by how she varies the language or dialect, accent or register, “code-switching” naturally as she goes.

Peshawar’s cosmopolitanism pulsates behind its ancient walls. This legendary thoroughfare, valley of flowers praised by emperors, and of teashops where traders brought many worlds together, where the imperial collided with the mercantile and spiritual through the millennia, is obscured by its shadow self: a city stubbornly resistant to newcomers and to change, addicted to custom. I find its immutable tribalism unsettling for many reasons, but most importantly because the idea of equality is deeply ingrained in me as an Islamic value. I’m taught at a young age to have a filter against discrimination, whether in stories or history, real life situations, TV dramas or politics. It is the principle at the heart of my belief system. I listen intently for balance. I ask if Helen of Troy had a say in the matter of launching “a thousand ships and burning the topless towers of Ilium,” why it was acceptable to call Shylock “cur,” why, around us, the dark-skinned Christians were called “sweepers” while the light-skinned were called “Sahibs,” why non-Pashto speakers were considered inferior, and women were stigmatized for a host of reasons that men were not, such as being childless, unmarried or divorced.

The Prophet of Islam, himself from a tribal society, rejected tribalism and discrimination. From watching The Message as a child, I remember the moment when the elite tribesmen of Quresh are stunned at the idea that Islam considers all people to be equal— “as equal as the teeth of a comb”— and that there is no claim of merit of an Arab over a non-Arab, or of white over a black person, or of a male over a female, only God-fearing people merit a preference with God. Equal as the teeth of a comb. Now, and throughout my life, I’ll continue to see gross violations of the principle of equality among the people who claim to be the Prophet’s followers and this phrase will often return to me.

At this age I tag along with Ami in her red Toyota Corolla, never fully admitting that I’m fascinated by how she selects everything from fabric to fruit, how she can make herself comfortable in all social situations, maintaining the same level of respect and consideration even as I hear her code-switching while speaking to a yogurt seller, a washerwoman, an electrician, a hairdresser, the school principal, the dentist, or the Governor. She manages with courteousness and a sense of humor, while remaining authentic and getting things done. I, on the other hand, find our class-ridden society too distressing; I don’t confront it though I care deeply and wish for change. While she turns and churns her many languages, I’ll funnel all of mine in the language of poetry, shutting out the speakers, keeping their concerns close.

Despite my insular lifestyle, I know that the residents of this great city are warm of heart and true of purpose, and I also know that their tribalism limits their potential and draws strange boundaries of alienation and attachment in relation to the place I call home. I identify and resist its narrow confines and selective loyalties— reminiscent of that most unfortunate combination of arrogance and ignorance characterized as “jahaliya” by scholar Karen Armstrong. The mystics and thinkers I read all lead me away from tribal attitudes, towards cosmopolitanism. Years later, when I go to Lahore to study at Kinnaird, I’ll tell my father that I miss home but I couldn’t be happier to have the opportunity to experience life in an intellectually open and stimulating environment, where voices different from one another have a better chance at being valued equally, where balance is possible.

As a student in Lahore, I feel terribly nostalgic when the sky turns a certain hue, or I catch a whiff of guavas or the delicate golden sundarkhani grapes or I overhear the sound of Pashto— I miss the sights, scents and sounds of home and the company of family friends, local as well as transplants, whom I’ll continue to miss later when I move to America, when the houses of childhood playmates appear in recurring dreams. One of the voices of Peshawar that infuses my memories with the deepest joy is the voice of Ami’s friend, the Pashto poet and professor Zeenat Khattak, who is among the most vivacious, spiritual, and loving people I’ve known. Her example teaches me that a poet’s subtlety of feeling and refinement of thought are possible to cultivate even where a gruff absolutism reigns supreme. I’m friends with her daughters throughout my young days but as I grow older I find a special kindred spirit in her— the only female poet with whom I have Peshawar in common, the only one who gives the city’s memory a many-faceted, mystic glimmer. Her sideways profile, with a rose in her hair, is forever part of the mythos I build of Peshawar.