by Pranab Bardhan

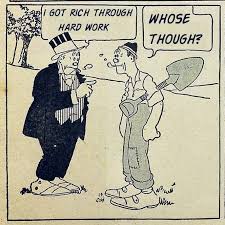

Some decades back the typical voting pattern in many democracies used to be that the rich and upper middle classes used to vote in general for right-leaning parties, while the relatively poor voted for left-leaning parties. But in recent decades this pattern has been shifting: many of the professional or more educated voters in some of those countries are increasingly going for left or green parties, while many of the poor working-class voters are turning to right-wing parties, sometimes led by populist demagogues. Thomas Piketty and his associates in a new paper issued by the World Inequality Lab have provided data to show that for 21 western democracies the more educated voters have over the years become more left supporters than the less-educated voters. Piketty has described this elite division between high-education and high-income people colorfully as that between the Brahmin Left and the Merchant (the corresponding Indian caste term would have been ‘bania’) Right. He does not go much into explaining this pattern but it is clear that as education expands (measured by average years of schooling of the adult population) the left or center-left parties now can have a viable base even in the relatively rich or upper middle classes. Education often makes one appreciate more liberal values, which may sometimes outweigh their worries about higher taxes that the left parties may inflict.

Some decades back the typical voting pattern in many democracies used to be that the rich and upper middle classes used to vote in general for right-leaning parties, while the relatively poor voted for left-leaning parties. But in recent decades this pattern has been shifting: many of the professional or more educated voters in some of those countries are increasingly going for left or green parties, while many of the poor working-class voters are turning to right-wing parties, sometimes led by populist demagogues. Thomas Piketty and his associates in a new paper issued by the World Inequality Lab have provided data to show that for 21 western democracies the more educated voters have over the years become more left supporters than the less-educated voters. Piketty has described this elite division between high-education and high-income people colorfully as that between the Brahmin Left and the Merchant (the corresponding Indian caste term would have been ‘bania’) Right. He does not go much into explaining this pattern but it is clear that as education expands (measured by average years of schooling of the adult population) the left or center-left parties now can have a viable base even in the relatively rich or upper middle classes. Education often makes one appreciate more liberal values, which may sometimes outweigh their worries about higher taxes that the left parties may inflict.

But this still leaves unexplained why the less-educated poor are leaning right. Of course the shocks of job losses due to global integration and automation have hurt them (particularly as low education makes it more difficult to adjust to changes in market demand and technology), but why are they turning right instead of turning toward far-left parties which are often anti-globalization and in favor of more social protection for working classes? I’d suggest that this is for two major reasons. The first has to do with economic policy, and the second predominantly cultural. Read more »

Among all the fascinating mythical creatures that populate the folklore of various cultures, one that stands out is

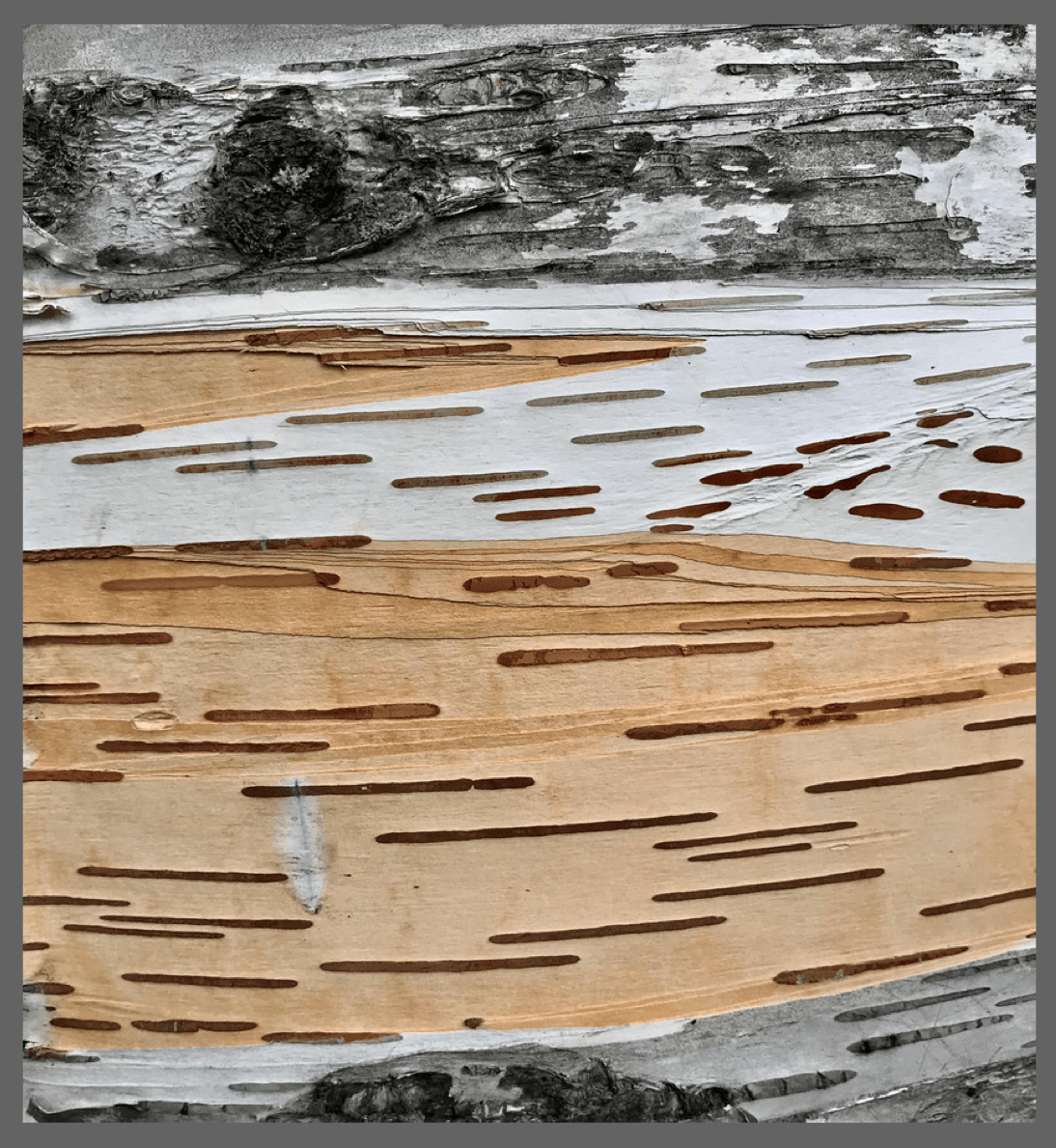

Among all the fascinating mythical creatures that populate the folklore of various cultures, one that stands out is  Sughra Raza. Beech Bark Landscape. June, 2021.

Sughra Raza. Beech Bark Landscape. June, 2021. Suppose you are Father God, or Mother Nature, or Mother God, or Father Nature — doesn’t matter — and you want to raise up a crop of mammals who can reason well about what’s true. At first you think, “No problem! I’ll just ex nihilo some up in a jiffy!” but then you remember that you have resolved to build everything through the painstaking process of evolution by natural selection, which requires small random shifts over time, with every step toward your target resulting in some sort of reproductive advantage for the mammal in question. Okay; this is going to be hard.

Suppose you are Father God, or Mother Nature, or Mother God, or Father Nature — doesn’t matter — and you want to raise up a crop of mammals who can reason well about what’s true. At first you think, “No problem! I’ll just ex nihilo some up in a jiffy!” but then you remember that you have resolved to build everything through the painstaking process of evolution by natural selection, which requires small random shifts over time, with every step toward your target resulting in some sort of reproductive advantage for the mammal in question. Okay; this is going to be hard. I’ve always loved the name Sinus Iridum (Bay of Rainbows), which describes a beautiful semicircular dark feature on the face of the Moon. Browsing a lunar map reveals other names equally beautiful or evocative: Sinus Concordiae (Bay of Harmony) and Sinus Aestuum (Seething Bay), for example. Other lunar plains with watery names include Mare Anguis (Serpent Sea), Palus Somni (Marsh of Sleep), and Mare Imbrium (Sea of Showers). Montes Harbinger is a group of mountains in Mare Imbrium; when they’re lit by the rising sun, they herald the approach of sunrise to Aristarchus crater.

I’ve always loved the name Sinus Iridum (Bay of Rainbows), which describes a beautiful semicircular dark feature on the face of the Moon. Browsing a lunar map reveals other names equally beautiful or evocative: Sinus Concordiae (Bay of Harmony) and Sinus Aestuum (Seething Bay), for example. Other lunar plains with watery names include Mare Anguis (Serpent Sea), Palus Somni (Marsh of Sleep), and Mare Imbrium (Sea of Showers). Montes Harbinger is a group of mountains in Mare Imbrium; when they’re lit by the rising sun, they herald the approach of sunrise to Aristarchus crater.

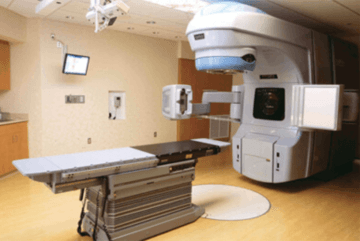

It’s the middle of July, 2020, the middle of a heat wave in the middle of the pandemic, and my first day in the radiation room. I stand in socks and starchy hospital gown before the Star Trek-ish linear accelerator, waiting for the technicians to fit me on the machine’s bed-like tray for best positioning. But in my mind I’m standing four years ago in the kitchen of my new home in Rhode Island, where beside me a cable company worker tapped in a phone number for advice about how to maneuver spotty Internet service into a happy ending. While he waited for his boss to call back, he mentioned, with a hint of wonder in his voice, “Y’know, this is my first day on the job after four months.”

It’s the middle of July, 2020, the middle of a heat wave in the middle of the pandemic, and my first day in the radiation room. I stand in socks and starchy hospital gown before the Star Trek-ish linear accelerator, waiting for the technicians to fit me on the machine’s bed-like tray for best positioning. But in my mind I’m standing four years ago in the kitchen of my new home in Rhode Island, where beside me a cable company worker tapped in a phone number for advice about how to maneuver spotty Internet service into a happy ending. While he waited for his boss to call back, he mentioned, with a hint of wonder in his voice, “Y’know, this is my first day on the job after four months.”

Climate change is such a terrifying large problem that it is hard to think sensibly about. On the one hand this makes many people prefer denial. On the other hand it can exert a warping effect on the reasoning of even those who do take it seriously. In particular, many confuse the power we have over what the lives of future generations will be like – and the moral responsibility that follows from that – with the idea that we are better off than them. These people seem to have taken the idea of the world as finite and combined it with the idea that this generation is behaving selfishly to produce a picture of us as gluttons whose overconsumption will reduce future generations to penury. But this completely misrepresents the challenge of climate change.

Climate change is such a terrifying large problem that it is hard to think sensibly about. On the one hand this makes many people prefer denial. On the other hand it can exert a warping effect on the reasoning of even those who do take it seriously. In particular, many confuse the power we have over what the lives of future generations will be like – and the moral responsibility that follows from that – with the idea that we are better off than them. These people seem to have taken the idea of the world as finite and combined it with the idea that this generation is behaving selfishly to produce a picture of us as gluttons whose overconsumption will reduce future generations to penury. But this completely misrepresents the challenge of climate change.

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations begins with this claim:

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations begins with this claim:

Helen Marden. Raja Ampat, 2018.

Helen Marden. Raja Ampat, 2018. I know someone—I’ll call him by his initials, KR—who is a Modi supporter. I have known KR for as long as I can remember. He is an intelligent, well-educated, well-travelled man. Now retired, he has a successful career behind him. He is Hindu, but he actively participated in the traditions and practices of other religions. Personally, I have great affection for him. Politically, we are now like oil and water. I usually avoid discussing politics with him because it inevitably ends in an argument: his view of Prime Minister Modi couldn’t be further from mine. In order to understand why people like him

I know someone—I’ll call him by his initials, KR—who is a Modi supporter. I have known KR for as long as I can remember. He is an intelligent, well-educated, well-travelled man. Now retired, he has a successful career behind him. He is Hindu, but he actively participated in the traditions and practices of other religions. Personally, I have great affection for him. Politically, we are now like oil and water. I usually avoid discussing politics with him because it inevitably ends in an argument: his view of Prime Minister Modi couldn’t be further from mine. In order to understand why people like him