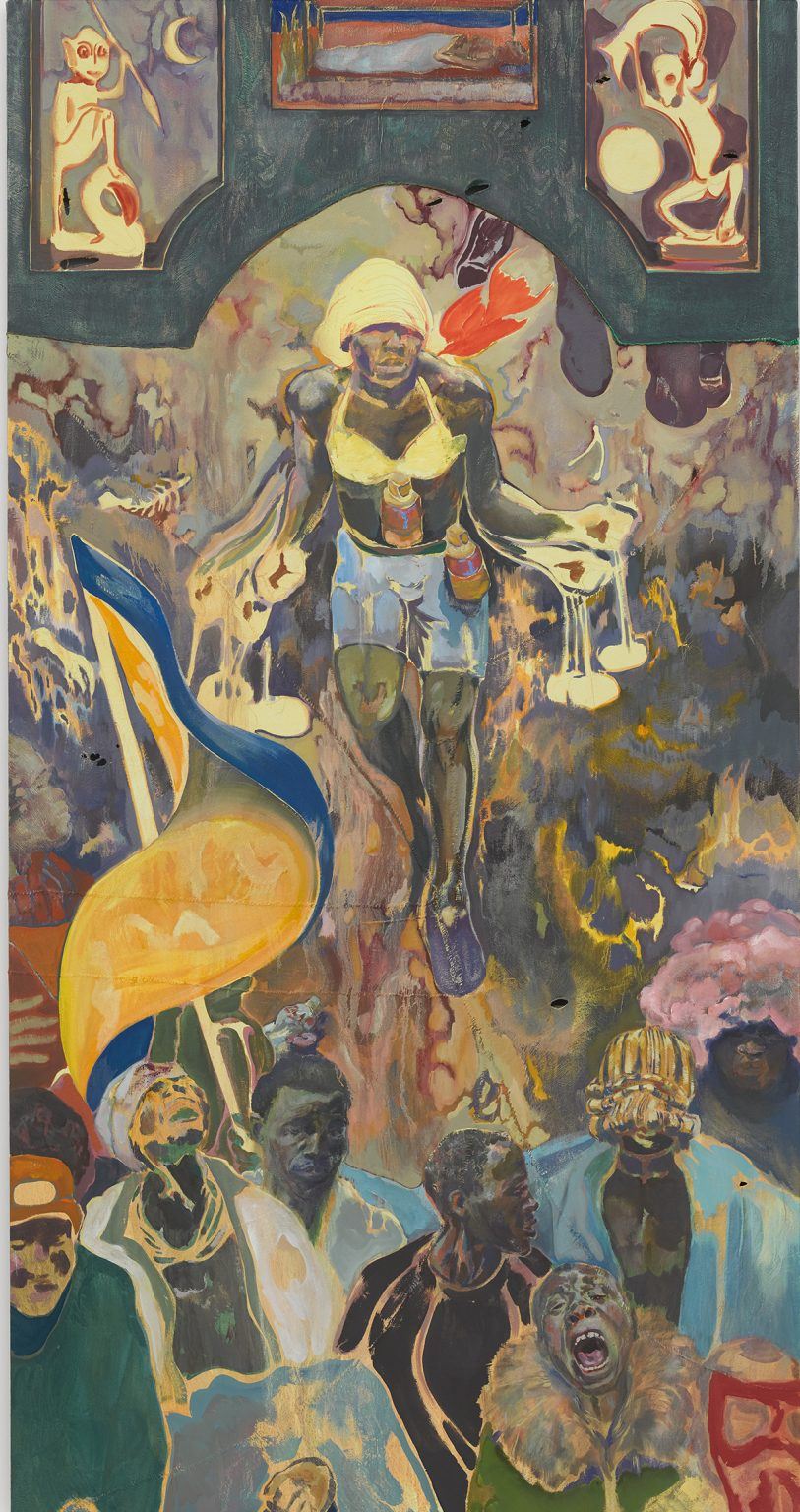

Michael Armitage. Pathos and The Twilight of the Idle. 2019.

Oil on Lubugo bark cloth.

by Claire Chambers

Covid-19 has led to various reactions akin to the various phases in the process of grieving. Davide Bertorelli observes in his chapter for The World Before and After Covid that ‘people have experienced differing degrees of anxiety, panic and disruption in every aspect of their lives’. Given what Bertorelli calls our current ‘mild collective psychosis’, it behoves us to learn from the previous global pandemic, the HIV/AIDS crisis.

Covid-19 has led to various reactions akin to the various phases in the process of grieving. Davide Bertorelli observes in his chapter for The World Before and After Covid that ‘people have experienced differing degrees of anxiety, panic and disruption in every aspect of their lives’. Given what Bertorelli calls our current ‘mild collective psychosis’, it behoves us to learn from the previous global pandemic, the HIV/AIDS crisis.

HIV is a virus that contains single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA), as does SARS-CoV-2. Transmission is by blood-borne infection through bodily fluids: blood, semen, and saliva. Typical routes are via sex, needles for intravenous drugs or blood transfusions, or vertical transmission from mother to baby. Like all viruses, HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) gets taken up into the host’s cells, mostly the white CD4 T cells. The virus then uses the host’s equipment to reproduce its own RNA. After killing off the helper T cells, HIV bequeaths the host an immunodeficiency.

HIV infections have three different phases. First is the primary infection stage, known as seroconversion, when the disease is caught. It usually takes seven to 21 days for patients to show the illness in flu symptoms and a rash. Then they get better and the virus lies dormant, possibly for years. The second phase is persistent generalized lymphadenopathy: carriers manifest swollen glands for quite some time but are otherwise healthy. The third phase is acquired immune deficiency syndrome itself, where patients develop an AIDS-defining illness. Opportunistic infections such as aspergillosis, cryptococcosis, candidiasis, toxoplasma, and cryptosporidium have famously been devastating for people with AIDS. Their immune systems cannot cope, whereas healthy people can easily fight off such infections. In addition to the AIDS-defining illness, the other characteristic of AIDS is that sufferers have a low CD4 count. Read more »

by Ethan Seavey

The end of the pandemic is far from near. The end of the American epidemic is far from near, too, but for those of us who made the decision to get one of three miracle vaccines, our COVID story is slowly wrapping up.

The COVID world was lonely, hidden, distrustful, terrifying, and endless. The COVID world was online, which excited me because then, I would’ve happily spent all day online. That changed.

Until there was a completed, ready-to-eat vaccine I believed we would be stuck in this digital alternate universe for five years. When every news channel boasted the efficacies of the new vaccines, I believed it’d be years before I got one, years before I’d have to worry about returning to the old world, the one so foreign to me now.

And now: it’s here. It’s knocking on the door, hard. I’m vaccinated and I’m supposed to jump back out into that real world, and that fills me with anxiety. I should’ve seen dozens of friends I promised to see, but now that I’m able, I can’t find the energy. I should’ve been a miserable unpaid intern four times by now, but I can’t get an e-mail back. I should be moving forward, and I can hope that I’m looking at that glorious summit by now, but I’m more comfortable thinking it’s just another false peak.

My future is made up of several fantasies. There’s one where I see myself a successful writer—that is: meeting my basic needs—and raising a happy family with the man I love. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Adele A Wilby

Many of us read with interest Ben Rhodes’ insider account of his time as a speech writer and advisor to Barack Obama during that historic presidency in his book The World as It Is: Inside the Obama White House. There were suggestions of his displeasure at some aspects of US politics in that publication, as for example the racism he thought Obama was subjected to while in office. His new book After the Fall: Being American in the World We’ve Made, goes further and is a clearer articulation of his concern about US and international politics. The conclusions he draws could be viewed as a personal coming of age in his understanding of the impact of American foreign policy on the world, and indeed experiencing and confronting more realistically, the ‘darker’ angels in US domestic politics.

Many of us read with interest Ben Rhodes’ insider account of his time as a speech writer and advisor to Barack Obama during that historic presidency in his book The World as It Is: Inside the Obama White House. There were suggestions of his displeasure at some aspects of US politics in that publication, as for example the racism he thought Obama was subjected to while in office. His new book After the Fall: Being American in the World We’ve Made, goes further and is a clearer articulation of his concern about US and international politics. The conclusions he draws could be viewed as a personal coming of age in his understanding of the impact of American foreign policy on the world, and indeed experiencing and confronting more realistically, the ‘darker’ angels in US domestic politics.

The phrase ‘after the fall’ in the title of the book hints at what is to come and suggests any one of two things, or indeed both. It could be seen as a metaphor to his personal experience after the transfer of power to Trump’s administration in 2016. Power, as many know, has its own intoxication and it would not be surprising if, on a personal level, Rhodes experienced the loss of his high-powered job and access to the highest office in the land as a ‘fall’. The personal reflections of this period in the book are certainly laced with indications of what was indeed an extra-ordinary career experience for Rhodes: it is the rare individual who gets to write ‘thousands’ of speeches for a president, let alone an historic president such as Obama, that Rhodes makes clear in this book that he did. Only time will tell however whether such a revelation about the extent of his involvement in shaping Obama’s thought will have an impact on Obama’s legacy, but such a revelation, we can assume, has Obama’s concurrence. Still, these personal accounts and reflections are worth a read in themselves. Read more »

by Thomas Larson

In 1994, Chauvet cave was discovered near the township of Vallon-Pont-d’Arc in southern France. The cave is a spectacular venue for the earliest known rock art made by our ancestors and in no way “primitive.” Deep inside the limestone cavern are hundreds of highly animated wall paintings of bison, bear, ibex, lion, rhinoceros, hyena, wooly mammoth, and horse, “signed” by the red-ochre handprints of the artists. The darkly etched charcoal drawings were sketched in the cave’s smoothed chambers, their walls rounded and pocked from water’s eonic hollowing. In the space are also pudding-like towers of calcium drips, whose conical shapes record the geologic heaping of age. The images, now protected as a World Heritage Site, were done between thirty-thousand and thirty-three thousand years ago.

In 1994, Chauvet cave was discovered near the township of Vallon-Pont-d’Arc in southern France. The cave is a spectacular venue for the earliest known rock art made by our ancestors and in no way “primitive.” Deep inside the limestone cavern are hundreds of highly animated wall paintings of bison, bear, ibex, lion, rhinoceros, hyena, wooly mammoth, and horse, “signed” by the red-ochre handprints of the artists. The darkly etched charcoal drawings were sketched in the cave’s smoothed chambers, their walls rounded and pocked from water’s eonic hollowing. In the space are also pudding-like towers of calcium drips, whose conical shapes record the geologic heaping of age. The images, now protected as a World Heritage Site, were done between thirty-thousand and thirty-three thousand years ago.

In the first ten minutes of Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2011), the film director and his crew hike up a rock face and squeeze through crawls spaces into the cave. Inside, the artists, paleontologists, and filmmakers don hardhats, test flashlights, and review the rules they must follow. The group’s one-hour descent, guarded viewing, and exit are filmed; afterwards, Herzog edits the footage by using two sound guides: the eerie, improvised evocations of cellist-composer Ernst Reijseger, to accompany the images, and Herzog’s voiceover commentary. Like a choirmaster, his soft, German-inflected, baronial English accompanies us through this sonic and architectural marvel. His voice warms and mystifies the claustrophobic space like a nurse talking us through an MRI. Read more »

by Chris Horner

One day, I used to say to myself and anyone else who’d listen, I’m going to write a book called ‘everything you know about these people is wrong’. I have given up on the idea, and I expect anyway that someone else has already done it. What prompted the repeated thought was the way in which so little of what well known thinkers and artists did or said is actually reflected in public consciousness, assuming it makes a showing at all. This can lead people to reject the idea of engaging with them before they’ve even had time to discover the ideas or experiences they might have learned from or enjoyed. Clearly, not everything will be to everyone’s taste, but you can’t know until you give it, or them, a try.

One day, I used to say to myself and anyone else who’d listen, I’m going to write a book called ‘everything you know about these people is wrong’. I have given up on the idea, and I expect anyway that someone else has already done it. What prompted the repeated thought was the way in which so little of what well known thinkers and artists did or said is actually reflected in public consciousness, assuming it makes a showing at all. This can lead people to reject the idea of engaging with them before they’ve even had time to discover the ideas or experiences they might have learned from or enjoyed. Clearly, not everything will be to everyone’s taste, but you can’t know until you give it, or them, a try.

What makes this problematic is that it is the least credible – and creditable – things that they have supposedly said or did that hang round them like a bad smell: Nietzsche the proto facist, Freud the sex mad coke addict, Marx the totalitarian etc. Popular beliefs about many of the key figures of modernity are often seriously askew, and sometimes at 180′ from the truth: Nietzsche was neither anti Semitic, nor a nationalist; Freud didn’t say it was ‘all about sex’; Marx wasn’t a proponent of a one party state, etc. It is almost as if whatever the popular view is of these figures, the truth lies in the opposite direction. So my instinct is to try to put the record straight. But what to do when the popular idea of an artist or thinker actually does correspond to something real – something true and bad?

Take Richard Wagner as a classic example. Read more »

by David Oates

In the plague year I walked every day, just about. It added up to a long journey of surprising homeliness. A solidarity of strangers. A neighborhood of distance and vista. A journey far and yet without the lie of the exotic.

It began in March over a year ago now. Since I was about to turn seventy, I had been planning a Big Do: hired a violinist from our Portland orchestra, plus a pianist who was a splendid performer (and also my teacher on alternate weeks). They would play for my birthday guests: I hoped for part of Beethoven’s Spring Sonata, and something from Mozart; and to celebrate my wonderful piano, a couple of Goldberg Variations and some Chopin. Who wouldn’t love such an evening?! I sent out invitations weeks ahead. The musicians rehearsed at my home.

But with one week to go, the picture clouded. Do you remember how our collective predicament came on? Each day, we wondered – how bad is this, really? On Monday I sent a placating email to my guests: “We’ll all be masked, but follow your conscience. . .” On Wednesday another: “If you can’t make it, I’ll understand. . .” The situation ripened sourly, direly. Almost hour by hour came new reports: infection, contagion, danger. With one day to go, I cancelled it.

And went for a walk. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

You may know everything that you need to know about the on-going “Critical Race Theory” debate. Indeed, you might have concluded that actually there is no such debate. If so, you’re not wrong. But I think it’s still worth asking, ‘Why is so much anger, seemingly out of nowhere, suddenly directed against this obscure academic subfield called Critical Race Theory?’

You may know everything that you need to know about the on-going “Critical Race Theory” debate. Indeed, you might have concluded that actually there is no such debate. If so, you’re not wrong. But I think it’s still worth asking, ‘Why is so much anger, seemingly out of nowhere, suddenly directed against this obscure academic subfield called Critical Race Theory?’

Critical Race Theory came out of a law school movement called Critical Legal Studies in the late 70s and early 80s. The key ideas that connected CRT to CLS were that (i) the law is much less coherent and much more indeterminate than scholars, judges, and lawyers like to admit. (ii) This indeterminacy both obscures and abets the laws’ real purpose, which is to protect the interests of those who created and enforce it. (iii) The law is racist, therefore, but how it is racist is not always obvious, and that’s the most important question. And so (iv) we should be more concerned with systematic, institutional racism than the fact that individual people hold racist beliefs or attitudes.

In response to the recent controversy, some academics have reacted by saying that this is all that there is to CRT and that we should distinguish CRT from (for example) Critical Race Studies – which is essentially CRT outside of law schools. I don’t think that before this debate started, however, many people would have drawn a sharp line between CRT and CRS. Nor is it quite accurate, I think, to say that this is all that there is to CRT. In my experience, CRT has come to be used in academia as shorthand for the view that (i) racism is a big problem in America and that (ii) that problem is more of a systemic, institutional one – than a problem about specific individuals having racists attitudes and beliefs. Read more »

by Mark Harvey

Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable.

Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable.

Democracies, like landscapes, take time to erode and the erosion isn’t always obvious to those living within its structure. Seemingly small things like villainizing the press, vicious attacks on political candidates, gerrymandering districts, voter suppression, and allowing vast amounts of money to enter the campaign process are all erosive forces that, taken individually, don’t seem like much. But taken together, over time, they break down democracies and invite darker forms of government.

When you start to speak about democracy in this country, it can get wispy and abstract in a hurry. Most of us were taught about democracy as school children in breathless, fabled terms. It’s hard to get past the myths of our founders and our founding to consider both how young and how clunky our democracy really is. For perspective, the oldest tree in the country is a bristlecone pine named Methuselah that sits in eastern California and had its beginning as a seed over 4,000 years before the convention in Philadelphia that hot summer of 1787. We think of our democracy as about 230 years old from the time when the Constitution was signed and George Washington first took office. But it’s only been 156 years since African Americans were freed and only about 100 years since women were guaranteed the right to vote by the Nineteenth Amendment. So our true democracy, at least on paper, is really only about 100 years old, closer to the lifespan of a cottonwood tree. And yet just 100 years into it, since the day when everyone was theoretically given the right to vote, things in the United States are wobbling and teetering. Read more »

by David J. Lobina

A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.

A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.

A particularly prominent aspect of how political nationalism does actually take hold in a large territory involves the central role a common language typically plays in the establishment of a national identity, a topic that has been at the heart of many studies of nationalism, though it is rarely treated satisfactorily.

Take two examples from the field of history, chosen almost at random but which nonetheless showcase some of the issues at stake. The author and historian Adrian Hastings once argued that England was already a nation-state in the 11th century, which he claimed was the case, in part, because of ‘the stabilising of an intellectual and linguistic world through a thriving vernacular literature’,[i] while the more modern historian Caspar Hirschi has recently paid attention to linguistic exchanges between different regions of Europe in the Middle Ages in order to probe what these interactions can tell us about how medieval peoples thought of each other. In particular, Hirschi points out that, as a case in point, hardly anyone in medieval Italy could understand what the merchants ‘coming from the north of the Alps were saying’, and it was precisely because of this that these people ‘were able to perceive the strange sounds as a ‘common’ language’, presumably thus identifying a common people to boot.[ii]

Such discourse is common enough and not too dissimilar to how laypeople talk of matters to do with language; it is, however, rather misleading and can sometimes lead scholars astray. In this sense, the study of nationalism could certainly benefit from the input of professional linguists. Read more »

…..“Time was so huge then.

…… It could not fail.”

…….. —from a poem by Nils Peterson

that’s the exquisite difference between then and now—

the space in time, the beautiful duration of it, its roominess;

its amplitude was great enough to contain many dreams,

multitudes —today time is crimped in cramps of years

months weeks days hours minutes,

but then we played through spans of eons —arms widespread,

palms unclenched, the distance from fingers tip to tip

left to right being light years — so, we crammed

light years with beginnings

while ends haunted the old we marked

nothing in futures or pasts

straddling imaginary mounts, we rode

only through now’s expanse and savored

it’s instant eternity which sustenance

has lasted a lifetime, whose taste has

lingered sweet

Jim Culleny

7/1/21

by Nicola Sayers

It’s hard to miss that the writer-director Nora Ephron is popular among women of a certain age and demographic (35–45ish, educated, mostly white, Anglo/American). Her volumes of essays (in particular I Feel Bad About My Neck, 2006) are staples in my peers’ bookcases (I am forty) in the way that Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying (1973) or John Gray’s Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus (1992) were in our mothers’ bookcases, and you’d be hard pushed to find a woman in this demographic who doesn’t list When Harry Met Sally among her favourite films.

It’s also hard to miss that it is women in this same demographic — at least in England, where I live — who often sheepishly side with J. K. Rowling, the unlikely figurehead of the ‘Should trans women be allowed to use female bathrooms?’ debate. I don’t have any hard data to back this up, but I have noticed that, by and large, older women automatically side with J. K. Rowling (if they even give the debate much thought), younger women can’t understand how something calling itself ‘feminism’ could do other than fully support trans rights, and women my age are often silent supporters: after a few glasses of wine among friends they’ll admit to one another a sympathy with Rowling’s perspective that they might not feel comfortable committing to paper (and when they do commit it to paper, as several journalists have, they are labelled ‘brave’).

These two distinct observations are not, I think, entirely unrelated. I’d like to offer a few more observations about this (my) group of women in an effort to better understand why Nora Ephron is so popular, and what is at stake in the J. K. Rowling debate. Read more »

by Deanna K. Kreisel

Now that Americans are emerging, blinking, into the post-pandemic daylight (perhaps temporarily! let’s not get too excited), a certain amount of stock-taking has been taking place. Some of it is braggadocious (languages learned, abdominal muscles honed), some of it is tragic (loved ones lost, livelihoods curtailed), and some of it is chagrined (Netflix queues emptied, drinking problems acquired). I am one of the lucky ones: a knowledge worker who was able to hunker down at home, with no children to wrestle and pin down in front of Zoom cameras; I lost no people and no material thing of importance. But that doesn’t mean that I escaped entirely unscathed. I have been cultivating a shameful new addiction in the secrecy of my own home, one that overcame me during the pandemic and still has me pinioned in its cruel, vise-like grip. My name is Deanna K., and I am a New York Times Spelling Bee addict.

It started innocently enough. My partner Scott and I used to do the New York Times crossword together all the time; during the pandemic lockdown, we got into the habit of stumbling out of our studies after hours of Zooming in order to eat lunch at the kitchen counter, and I would bring my iPad so we could do the crossword while we ate. Then, one fateful day, Scott noticed the bright yellow-and-black bumblebee logo on the Puzzles page, invitingly twitching its plump little bumblebutt at us like a schoolyard pusher offering a free taste. We gave it a go, found it intriguing and just the right amount of maddening, and were completely sucked in. Read more »

by Mike O’Brien

I’m self-conscious about the style of my writing. Not that I fear my style is flat or derivative otherwise wanting; quite the opposite, in fact. This isn’t too presumptuous, because I have been told many times, by people whose tastes I esteem highly, that my writing is admirably well composed. Given that I have a strong natural tendency to doubt the merits of my own work, my acceptance of such compliments as accurate and warranted is a testament to how many times I have heard them. But a different doubt arises, having put to rest that first one; since I tend to compose pieces which argue for some position on questions of substance, do these succeed (assuming that they do succeed) because of the quality of their arguments and the correctness of their premises, or do they merely enchant by aesthetic and pathetic overtures? (I’ve heard that very attractive people can suffer such doubt about all their socially-mediated successes in life, and I can tell you it’s true.)

On the one hand, if I am arguing for a point about which I really do care and of which I am myself convinced, I don’t really care why people agree with me, so long as they conduct themselves in conformity with my position. Such points are rare, and are generally matters of ecological or existential survival. After so many years staring into assorted abysses of environmental and civilizational catastrophe, much of what animates public debate (especially of the ephemeral “Twitter war” variety) is of no more interest to me than the barking of dogs. Out-barking them would not serve my ego, no matter how impressed I might imagine the dogs to be.

On the other hand, there are strategic considerations at play in arguing about important matters in public. If one supposes one’s own position to be favoured, even singularly indicated, by facts and logic, then one may jeopardize their long-term success by devaluing factual evidence and logical rigour in pursuit of easy though tenuous agreement. A cheap trick is one easily stolen and turned against its employer, and even if not so reversed it still disgraces the user. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Thomas O’Dwyer

Truth may be the first casualty of war or, nowadays, of politics, but few of us would have thought of using a map to look for lies. But thanks to Google Maps and other geographic meddlers, there may now be fewer lies in a Donald Trump speech than on the face of the good Earth. It’s not hard to find places Google doesn’t want you to see, but not all are as obvious as its satellite image of a part of southern Tibet. There, the entire village of Guwacun lies under an unsubtle grey rectangle. Such geographical censorship goes far beyond pandering to mandarins in some Chinese ministry of paranoia. Take democratic, advanced, high-tech Israel, for example. Only low-resolution images of the entire country and the surrounding Palestinian territories are available online. Google alone is not to blame for this — America is. In 1997, the US government passed a law called the Kyl–Bingaman Amendment. This law prohibited American authorities from granting a license for collecting or disseminating high-resolution satellite images of Israel. The US mandated censorship of commercial satellite images for no other country in the world except Israel.

The largest global sources of commercial satellite imagery include online resources, such as Google and Microsoft’s Bing. Since they are American, the US has used the “Israel images amendment” as a powerful tool for suppressing information. Hence, images of Israel on Google Earth are deliberately blurred. Strangely, anyone in the world can zoom in on crisp and detailed pictures of the Pentagon or GRU headquarters in Moscow, but all one can see of Tel Aviv’s public central square and gardens is a fuzzy grey blur. This odd restriction has frustrated archaeologists and other scientists who depend on satellite imagery to survey areas of interest to their disciplines. It does, however, enable Israel to conceal practices in the occupied Palestinian territories that attract international censure. These include expanding Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Golan Heights, demolitions of Palestinian homes, and abuses of power by the military in clashes with Gaza. Read more »

I wasn’t pelting stones

Ten years ago

I didn’t even know what protesting meant

I was Kashmir’s youngest pellet gun victim

Only 20 months old then

I lived with my family

In Shopian

I was playing inside my house

when the army sprayed teargas

All around

Grey smoke entered our home

The air was unbreathable

I started to vomit

My five-year-old brother squirmed

My mother cradled me in her arm

She took my brother by his hand

We tried to flee

But were trapped in the chaos

My mom pulled my brother behind her

She covered my face with her hand

A soldier sprayed pellets at us

One pellet hit my mom’s hand

Two hit my eyes

I screamed, “Muma, tout” [burning]

Blood dripped from my eyes

I passed out

I had started learning to name things

***