Stuck is a weekly serial appearing at 3QD every Monday through early April. The Prologue is here. The table of contents with links to previous chapters is here.

by Akim Reinhardt

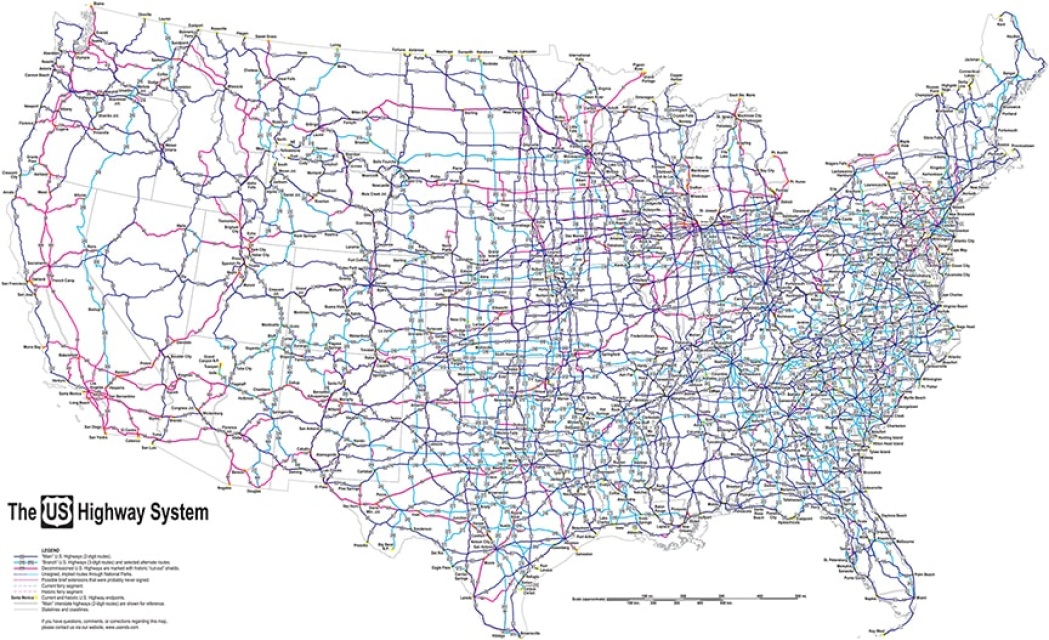

This song got caught in my head as I circled the country in my 1998 Honda. Leaving New York City, I drove west into the heart of America, up to the Dakotas, out to California, down the Golden State, and then back along the Southern route before angling northward to Baltimore. I saw nearly all the America you can see. But of course there’s not just one America. There are many.

This song got caught in my head as I circled the country in my 1998 Honda. Leaving New York City, I drove west into the heart of America, up to the Dakotas, out to California, down the Golden State, and then back along the Southern route before angling northward to Baltimore. I saw nearly all the America you can see. But of course there’s not just one America. There are many.

The environment shifts dramatically along the way. So too do the people. From densely packed cities to sparsely populated rural areas. From little towns dotting the countryside to sprawling suburbs that fade into forest or desert or grasslands. It is a vast expanse, the world’s third largest nation in both square mileage (behind Russia and Canada) and population (behind China and India). When I was a kid there were 200,000,000 people. Or so a Burger King commercial told us. Now we’re closing in on 350,000,000.

It takes all types. But of course some types get more attention than others. Mass media consistently highlight white people, the major exception being black entertainers (mostly athletes and singers) and criminals. Men continue to dominate positions of power and prestige. The coasts boast most of the population, and sneeringly refer to the middle as “fly over country.” And the cities and suburbs, home to the vast majority of Americans, largely ignore the small towns and rural areas that actually makeup most of the physical landscape.

My own life illustrates many of America’s different faces.

I’ve lived in New York City, Michigan, Nebraska, Arizona, and Maryland. I have family in the Bronx, small town North Carolina, and two very different parts of California: Greater LA and Central Valley. I’m not multi-racial, but my relatives do cover a variety of religions, including Judaism, several protestant denominations, and atheism. My mother’s parents were immigrants and English was her second language, while my father’s family has been here for centuries.

I cherish this range of difference in myself, my family, and my nation. But of course it has never been without tensions, either on a national or personal level. My Jewish grandparents tried everything they could to keep their daughter from marrying my father because he was a gentile. When my mother got pregnant, they encouraged my father’s conversion and insisted that I and my sister be raised Jewish. My Christian grandmother was deeply saddened by this because she believed my sister and I, never baptized, would go to hell when we died. My father never told her of his own conversion to Judaism so as to spare her additional pain. My Jewish uncle once disinvited me from his Passover seder (holiday dinner) because I was living with my Irish Catholic girlfriend.

Music has always allowed me to embrace or at least acknowledge difference. That’s not to say music brings everything into harmony, so to speak; it’s as much about tension as it is release. But if you’re really listening, music makes it impossible to blithely paper over our differences. In 1989 I saw George Clinton and Parliament/Funkadelic in Detroit, and the audience was almost entirely black. Ten years later, I saw them in Missoula, Montana, and the crowd was almost entirely white. Music doesn’t necessarily bring people together, but it can connect them in ways that most things can’t or don’t.

Growing up in New York City in the 1970s and 1980s, I learned about music from my parents, from commercial radio stations, from friends, and from piano lessons beginning at age 13. The result was a healthy dose of all kinds of rock and pop, with strong servings of soul, R&B, funk, disco, and even a little classical. As a kid, my dad would occasionally play records by Spanish flamenco guitarist Carlos Montoya, and jazz pianist Errol Garner. In junior high school I was one of the few white students who preferred disco to rock (you had to choose). In high school I was one of the few white rockers who preferred Southern rock to British stalwarts like Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, and The Who. I left home at age 17, thinking I was musically well rounded. But spinning records as a radio disc jockey in my 20s and early 30s is what really expanded my horizons.

From 1987 – 2000 I worked at two public radio stations. WCBN-FM is the University of Michigan’s student station. KZUM-FM is a community station in Lincoln, Nebraska that offers a wide range of musical formats instead of NPR talk or a single format like classical or jazz. At both stations I had freeform shows. Freeform is a format in which the DJ not only programs the music, but also has virtually unfettered leeway in picking the songs, regardless of genre. You’re expected to be wide ranging. The experience changed my life.

WCBN gave its freeform DJs complete freedom with one caveat: don’t play anything you can hear on commercial radio. That forced 19 year old me to stretch and grow. I began to more seriously investigate musical forms of the African diaspora, including blues, mid-century R&B, jazz, zydeco, reggae, gospel, and music from across Africa itself. I also seriously encountered avant garde music for the first time, which challenged my conceptions of what music actually is or could be. Later, at KZUM I plumbed the depths of Americana, including country, folk, bluegrass, and American Indian musics, as well as various international forms ranging from Mexican conjunto to Cuban jazz to Gypsy folk to Indian (Asian) classical.

Perhaps you’ve had similar experiences with music. Or food, or film, or fashion. Perhaps you can’t imagine living in a world with just one nation’s cuisine or beverages, or just one culture’s style and grace, or just one language’s way to say “Hello,” “Thank you,” or, “I love you.”

Or perhaps you know what you like and you stick to it. I respect that. But being just one thing was never really an option for me, not if I was being honest with myself. Not with my family. And certainly not once I started traveling and living across the United States. There are certainly many, many places that are very different from America, but few places that boast as much difference as America.

Missouri, perhaps more than most states, slices through America’s regions. Parts of the state are very Midwestern. Other parts are fairly Southern. And some are downright Western. On its eastern edge is post-industrial St. Louis, nestled at the juncture of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. On the other side is Kansas City, cattle and rail hub, and gateway to the West. The quintessential American college town of Columbia is smack dab in the middle. And a wide range of farms and towns spread across its prairies, forests, and mountains.

A little over 6 million people in all. And home to The Domino Kings of Springfield, Missouri. A virtuoso band that almost no one’s ever heard of. Authors and performers of “Walk Away if You Want to,” a perfect little country song that got stuck in my head as I drove down the West coast and across the southwestern desert in 2014. The crown jewel from the last of their four albums cut between 1999 and 2005. A gem that I first encountered on a country music sampler by the final record company to sign them, Hightone out of Austin, Texas (defunct since 2008).

“Goddamn it, try it!” my father would demand when I was a kid looking to avoid a new food. “You don’t have to finish it if you don’t like it, but you can’t not try it. Now take a bite.”

Akim Reinhardt’s website is ThePublicProfessor.com