by Bill Benzon

When I was growing up in the 1950s and 1960s Westerns were pervasive on television and at the movies. Where they the dominant genre of the era? Perhaps, I don’t really know. But whatever the numbers say, the were very important. Correlatively, science fiction was a relatively minor genre, both on television and on the big screen. Now the situation is reversed. Science fiction is pervasive while Westerns, if not as scarce as hens teeth, certainly do not command the broad attention they once did.

What are we to make of this? Westerns look to the past, to the founding of America. How the West Was Won (1962) was the story of America, and it won three Academy Awards. The bespeak and confident America. Star Trek is a bit different. It, the entire franchise (from 1966 through to the present), is set in the future while America has only a tenuous presence in it, a step back in time every now and then. America is in transit. Similarly, Star Wars, the whole throng of stories, is set in a universe long ago and far away. America has disappeared.

Why? Tastes change, no? Yes, but why? For one thing, America has changed as well. That’s what interests me, the relationship between changes in America and changes on the Big Screen. I want to examine that by focusing on two films, The Forbidden Planet (1956), a science fiction classic from the era when science fiction was a minor genre, and The Terminator (1984), another classic science fiction film, one in a franchise in an era of franchises, and an era when science fiction was becoming pervasive.

The argument I am going to make, a loose argument, a speculative argument, and therefore the most interesting kind of argument we can make about the stories we tell ourselves, is that these are, at the core, the same story. If they are, on the surface, so very different – which they are – that is because they speak to radically different psycho-cultural circumstances. The America of 1956 was confident of itself and of the future. The America of 1982 was badly shaken and searching for itself. Exactly between those two dates, 26 years apart, we have the Apollo moon landing in 1969. Read more »

It wasn’t effortless but we managed to mollify, sidestep and defy enough authorities to be legally resident in Finland for the month of July. Never mind shoes and belts off and toothpaste in a plastic bag. No, do mind; do that too. But add PCR test results, Covid vaccination cards and popup, improvised airport queues. And a novel Coronavirus variant: marriage certificates on demand.

It wasn’t effortless but we managed to mollify, sidestep and defy enough authorities to be legally resident in Finland for the month of July. Never mind shoes and belts off and toothpaste in a plastic bag. No, do mind; do that too. But add PCR test results, Covid vaccination cards and popup, improvised airport queues. And a novel Coronavirus variant: marriage certificates on demand.

Cancer has occupied my intellectual and professional life for half a century now. Despite all the heartfelt investments in trying to find better solutions, I am still treating acute myeloid leukemia patients with the same two drugs I was using in 1977. It is a devastating, demoralizing reality I must live with on a daily basis as my entire clinical practice consists of leukemia patients or leukemia’s precursor state, pre-leukemia. My colleagues, treating other and more common cancers, are no better off. I obsess over what I have done wrong and what the field is doing wrong collectively.

Cancer has occupied my intellectual and professional life for half a century now. Despite all the heartfelt investments in trying to find better solutions, I am still treating acute myeloid leukemia patients with the same two drugs I was using in 1977. It is a devastating, demoralizing reality I must live with on a daily basis as my entire clinical practice consists of leukemia patients or leukemia’s precursor state, pre-leukemia. My colleagues, treating other and more common cancers, are no better off. I obsess over what I have done wrong and what the field is doing wrong collectively.

Covid-19 has led to various reactions akin to the various phases in the process of grieving.

Covid-19 has led to various reactions akin to the various phases in the process of grieving.

Many of us read with interest Ben Rhodes’ insider account of his time as a speech writer and advisor to Barack Obama during that historic presidency in his book The World as It Is: Inside the Obama White House. There were suggestions of his displeasure at some aspects of US politics in that publication, as for example the racism he thought Obama was subjected to while in office. His new book After the Fall: Being American in the World We’ve Made, goes further and is a clearer articulation of his concern about US and international politics. The conclusions he draws could be viewed as a personal coming of age in his understanding of the impact of American foreign policy on the world, and indeed experiencing and confronting more realistically, the ‘darker’ angels in US domestic politics.

Many of us read with interest Ben Rhodes’ insider account of his time as a speech writer and advisor to Barack Obama during that historic presidency in his book The World as It Is: Inside the Obama White House. There were suggestions of his displeasure at some aspects of US politics in that publication, as for example the racism he thought Obama was subjected to while in office. His new book After the Fall: Being American in the World We’ve Made, goes further and is a clearer articulation of his concern about US and international politics. The conclusions he draws could be viewed as a personal coming of age in his understanding of the impact of American foreign policy on the world, and indeed experiencing and confronting more realistically, the ‘darker’ angels in US domestic politics. In 1994, Chauvet cave was discovered near the township of Vallon-Pont-d’Arc in southern France. The cave is a

In 1994, Chauvet cave was discovered near the township of Vallon-Pont-d’Arc in southern France. The cave is a  One day, I used to say to myself and anyone else who’d listen, I’m going to write a book called ‘everything you know about these people is wrong’. I have given up on the idea, and I expect anyway that someone else has already done it. What prompted the repeated thought was the way in which so little of what well known thinkers and artists did or said is actually reflected in public consciousness,

One day, I used to say to myself and anyone else who’d listen, I’m going to write a book called ‘everything you know about these people is wrong’. I have given up on the idea, and I expect anyway that someone else has already done it. What prompted the repeated thought was the way in which so little of what well known thinkers and artists did or said is actually reflected in public consciousness,

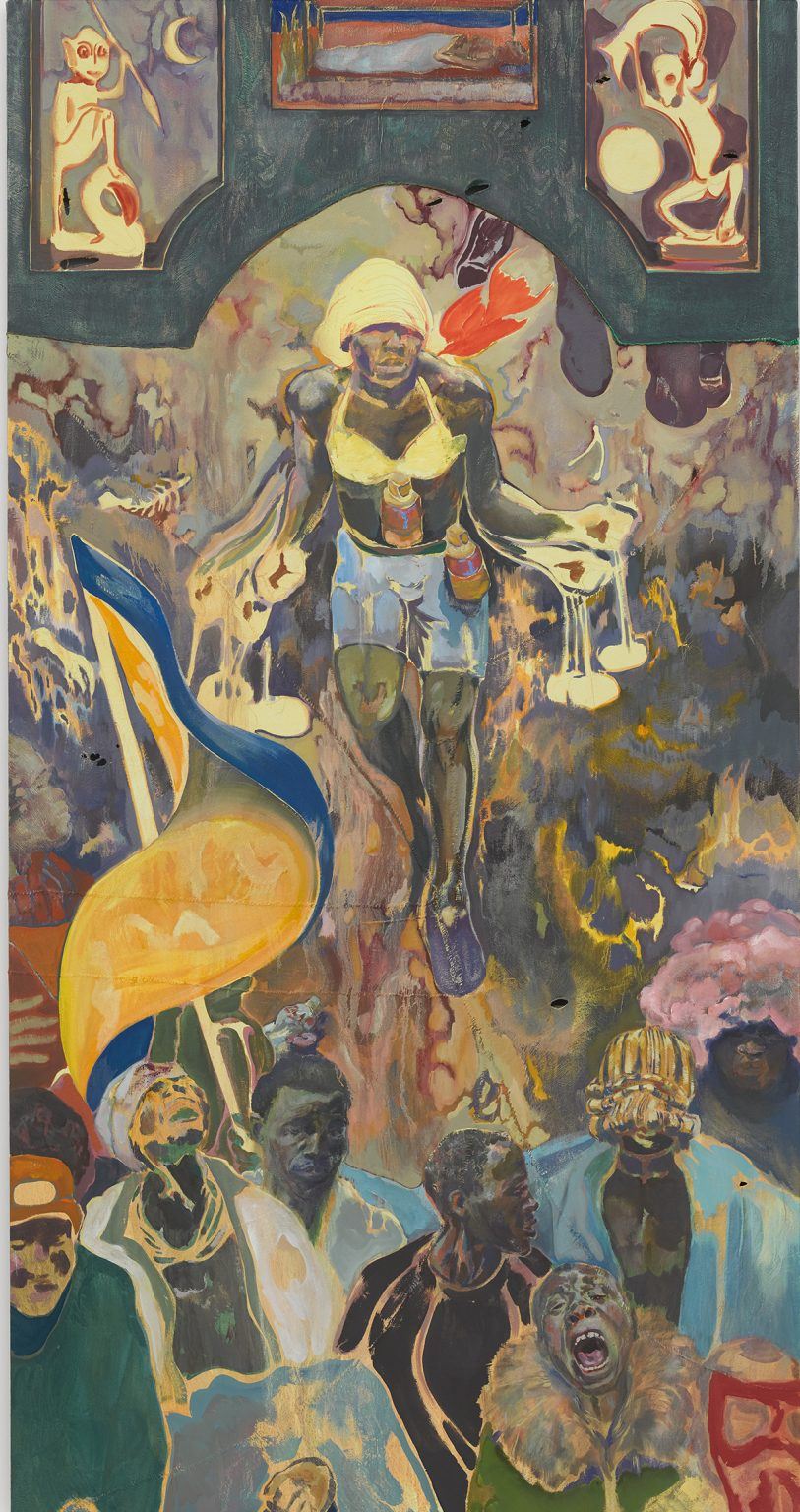

You may know everything that you need to know about the on-going “Critical Race Theory” debate. Indeed, you might have concluded that actually there is no such

You may know everything that you need to know about the on-going “Critical Race Theory” debate. Indeed, you might have concluded that actually there is no such  Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable.

Where I live in Colorado there are unstable elements of the landscape that sometimes fail. In severe cases, millions of tons of rock, silt, sand, and mud can shift, leading to massive landslides. The signs aren’t always evident because the breakdown in the structural geology often happens quietly underground. The invisible changes can take hundreds or thousands of years, but when a landslide takes place, it is fast and violent. And the new landscape that comes after is unrecognizable. A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.

A number of issues in the study of nationalism ought to be widely accepted nowadays, most notably perhaps the claim that political nationalism – the idea that a citizen pledges allegiance to a nation-state rather than to a village or a town – is a modern phenomenon. After all, nationalism properly takes hold in a territory when modern tools such as universal schooling are employed to produce a national identity – the inhabitants of a territory must speak the same language and recognise a common culture if a nation is to surface – and this is a product of the last 200 years. A national identity doesn’t come about on its own.