by Deanna K. Kreisel (doctorwaffle.substack.com)

One of the most painful aspects of losing a beloved to death is the feeling that you, and the world, are moving on while they remain forever in a rapidly receding past. I think a lot about how my dear friend Elizabeth will never know that the star of “The Apprentice” became President of the United States of America, and it grieves me that my mom and dad will not get to enjoy my moving closer to home again after they died. Probably there’s a lengthy German compound noun for this phenomenon, but I will coin the English term “fugitive melancholy” to refer to this painful sense of time fleeing away from dead ones left behind.

We can also feel fugitive melancholy, proleptically, for ourselves. We will live to see only a little bit of the future, compared to the sweeping sense of historical scale we gain by contemplating the past. Retrospection gives us the narcissistic sense that we are omniscient observers of human events, and also tricks us into thinking that this moment in which we are living is the culmination of time. We are always in the position of Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History, his face turned toward the past while history “unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it before his feet.” In the same essay, Benjamin remarks that we do not feel envy for the future, that our idea of happiness is steeped in the time in which we happen to live. Yet I disagree. The melancholy we feel at the prospect of our own deaths is indeed a species of envy, at least of the near future: of those who will witness the outcome of current events. As we grow older we fall prey to a frustrated desire for narrative closure, knowing that we will not get to see how everything turns out.

Fugitive melancholy might help us understand our mass resistance to meaningful action on climate change. Unconscious resentment at the thought of our own deaths leads to an inability to fully imagine—or care for—the world after we are gone. Naomi Klein recently differentiated what she terms “soft denial” from the hard-core refusal to believe the consensus of the scientific community on climate change. Those in soft denial understand that global warming is happening and are even capable of occasionally—briefly—taking in its full implications, “but then, inevitably, we seem to forget. Remember and then forget.” Yet in the seven years since Klein coined the term “soft denial,” the problem has mutated, shifted form: “denial” no longer seems to capture our current state of near-constant helplessness and despair. Read more »

A rose is a rose is…well, you know. Botanically, a rose is the flower of a plant in the genus Rosa in the family Rosaceae. But roses carry the weight of so much symbolism that a rose is seldom only a rose.

A rose is a rose is…well, you know. Botanically, a rose is the flower of a plant in the genus Rosa in the family Rosaceae. But roses carry the weight of so much symbolism that a rose is seldom only a rose.

By the time I started regular school my father’s home-schooling had prepared me enough to sail through the various half-yearly and annual examinations relatively easily. Indian exams, certainly then and to a large extent even now, do not test your talent or learning ability, they are mainly a test of your memorizing capacity and dexterity in writing coherent answers in a frantic race against time. I found out that I was reasonably proficient in both, and that it is for the lack of proficiency in these two qualities some of my friends, whom I considered highly imaginative and creative, were not doing so well in school.

By the time I started regular school my father’s home-schooling had prepared me enough to sail through the various half-yearly and annual examinations relatively easily. Indian exams, certainly then and to a large extent even now, do not test your talent or learning ability, they are mainly a test of your memorizing capacity and dexterity in writing coherent answers in a frantic race against time. I found out that I was reasonably proficient in both, and that it is for the lack of proficiency in these two qualities some of my friends, whom I considered highly imaginative and creative, were not doing so well in school.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat?

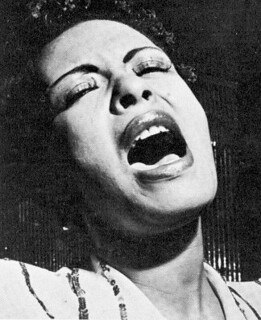

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat? Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace.

Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace. Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.

Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.