by Ethan Seavey

The end of the pandemic is far from near. The end of the American epidemic is far from near, too, but for those of us who made the decision to get one of three miracle vaccines, our COVID story is slowly wrapping up.

The COVID world was lonely, hidden, distrustful, terrifying, and endless. The COVID world was online, which excited me because then, I would’ve happily spent all day online. That changed.

Until there was a completed, ready-to-eat vaccine I believed we would be stuck in this digital alternate universe for five years. When every news channel boasted the efficacies of the new vaccines, I believed it’d be years before I got one, years before I’d have to worry about returning to the old world, the one so foreign to me now.

And now: it’s here. It’s knocking on the door, hard. I’m vaccinated and I’m supposed to jump back out into that real world, and that fills me with anxiety. I should’ve seen dozens of friends I promised to see, but now that I’m able, I can’t find the energy. I should’ve been a miserable unpaid intern four times by now, but I can’t get an e-mail back. I should be moving forward, and I can hope that I’m looking at that glorious summit by now, but I’m more comfortable thinking it’s just another false peak.

My future is made up of several fantasies. There’s one where I see myself a successful writer—that is: meeting my basic needs—and raising a happy family with the man I love.

There’s another fantasy I lean into when I’m emotionless and trapped in bed, where COVID’s cruel cousin emerges and maybe this time masks don’t work and I’m allowed to stay in this pandemic stasis eternally, blurring the line between the digital world and this, the real one, until they’re one and the same.

There’s a third fantasy where the human world rights itself for a few years, until we’re faced with an extinction-level global destruction that ends what little life I’d built and ends in death and doomsday prepping. That’s a good one to visit when you’re standing alone on the beach and you see the tidal wave of responsibilities rapidly approaching.

There’s a fantasy that I’ll log on one day and learn that I’ve gone viral, and there’s a fantasy that I’ll never have to touch another phone in my life. There are a thousand fantasies in which I’ll be successful; and there are countless fantasies that I’ll never have to do any work because of some destructive deus ex machina.

But either none of that will happen, or one of those will happen, and it’ll be less than I expect. Most likely I’ll join the queue of people walking with their necks bent forward, their phones in their hands, their brains totally satisfied with the chemicals that come with this happy little glass block, walking into the smoking sun without looking up.

The COVID world proved that we can substitute this world with a digital one. In 2020, I was scrolling miles on my phone every day, and doing little else. It overloaded my ability to see the beauty online, and at the end of the day, my eyes felt dry and my brain felt cracked like parched earth.

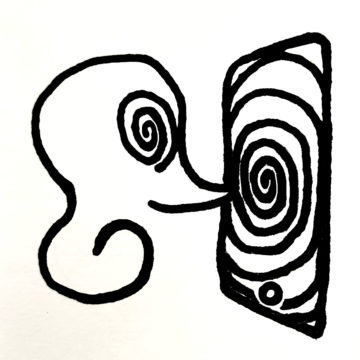

Are you afraid of living the rest of your life online? It should feel as natural as non-existence at the end of life, but when the time finally came—yes, that time is already here—when seeing another human was restricted to the digital sphere, you were filled with anxieties. You, who grew up with these tools, who has used them in classrooms for many years now, who loves the phone in conjunction with a real life, you saw how it would all turn out over the next year. You knew that you’d develop the pattern you did. You’re consuming your phone constantly, watching Youtube as you walk around the house, flicking through the news during lunch, stubbing toes because your eyes are focused on a glass block twelve inches from your face. You take class on your laptop but your focus is on your phone, on which you play nonsense games and switch between your different social medias to compound your time spent onscreen.

Most popular social medias employ “infinite scrolling,” an effective method of engagement where content is personally served to you, endlessly. Think of it like being at a restaurant. You order one beer. When you finish that the waiter asks if you’d like another, and you make the decision, then and there. However, if the wait staff simply refills your cup, for free, even if you don’t necessarily want them to, you’ll drink forever. How many beers have you had? How long have you been here? Is it dark outside? It doesn’t matter—the cup is full again.

I’ve been an infinite scroller ever since I was gifted an iPhone, which was right around my freshman year at a Catholic high school. These two new worlds I entered could not have been more dissimilar. At school I was taught to think one way and to feel powerful for thinking that way; and on my phone, I was learning to be open-minded and promote radical acceptance in the Queer community. At school I was straight and quiet; online I was gay and anonymous, just looking, unsure how to exist and not be uncovered by the real world. I saw the beauty of the online world without seeing the ugly pixels making it, without feeling its effects on my self.

Infinite scrolling is a sensory deprivation pool. On days when living is especially hard, where life feels heavy and the distance between you and yours is unnavigable, you climb into bed with jeans on, knocking off the folded clothing and books that rest on the quilt, ignoring them as they fall to the wooden floor. You sit in a way that locks up your shoulder and your elbow, though it hurts more with every passing minute—but you feel none of that, because you’re happily wandering online. Reading one post after another, never laughing though they’re supposed to be funny, never noticing your body in all this. In this moment: you are your phone. It is your entire field of vision, it is a constant source of catchy songs, it is always refilled with social updates. It is fulfilling both your desire to be productive and your inability to get out of bed. You switch apps every ten or fifteen minutes when a new notification appears at the top of the screen; you bounce between Instagram and Snapchat and Tiktok and when you’ve been online long enough you open Facebook, too.

Infinite scrolling is a lottery without consequences. You spend a token of time in the hopes of finding a jackpot in your feed. Here, a jackpot is something that you can re-post, share with a friend, or bookmark to immortalize it. When you find one of these you feel accomplished and feel that the time spent was worth it, like sifting dirt for hours to find a chunk of pyrite you contentedly pretend is gold.

Infinite scrolling is a drug like nicotine, not intoxicating but slightly altering, gratifying when hit. One puff doesn’t hurt, but when you’re an avid smoker of the internet, on the worst days all you can do is lie on your back, blowing smoke up towards the ceiling fan. And you rationalize it, you say you’ve had a hard day, that pulling yourself out of your body for just a few hours can stall those heavy anxieties. The phone is at its most destructive when you’re the most vulnerable, most upset and desiring numbness.

When you’re infinitely scrolling, you wind up watching what you do not enjoy, and you find that you haven’t time in the day for what you do. The phone happens to you; but it’s you who has to read the book.

Are you aware that you can turn off your phone and the world will be quiet? Quiet enough to notice the little things, like wildflowers that you call weeds, or the steadily increasing noise of rustling leaves until they crescendo into a gust of wind on your face. You can read Walden and not the thousands of summaries published online, and you can read Into the Wild without skimming headlines to decide if McCandless was brave, brash, stupid, or enlightened. You can decide for yourself without looking for the voices that support your belief.

In legends I’ve heard there was a world before this digital one. I’ve heard that my parents looked up whatever they didn’t know in encyclopedias they’d replace every decade. I’ve heard that without Google, they had to trust that their neighbors knew how to do what they didn’t.

There was a world before this digital one, and I’m trying to understand it. I’m reading Tolstoy to explore a world where people found fulfillment in a life of manual labor, pensive relaxation, and frivolous aristocratic drama. A world in which to be bored. I am never bored. I haven’t been bored in years. My attention hops from one activity to another, because it has been trained to work in life in the same way I do on my phone: switching between the same five apps; doing this then that then this then that because I cannot stop.

There was a world before this digital one, and to fully see it, I’ve turned my phone into a tool. It started about a year ago, when I thought COVID was first “ending,” that happy June of 2020 where masks were widely worn and I could see a few friends again. It was then that I decided that my phone brought me nothing but mindless, infinite content, and I deleted all but one of my social media apps.

I was still addicted to my phone, but I ended up mindlessly scrolling through the one app instead of the five. And now, a year later, I’ve decided it’s still not enough and have stripped my phone again. I purged more apps, turned off notifications from robots (not real people trying to reach me) and spread my apps across many home screens so I have to swipe through seven pages to find what I’m looking for.

And, most effectively, I eliminated color from my phone screen, reserving that for the real world. At times it feels tedious, that I cannot see the color my phone sees when I take a picture; but when I look up from my black and white phone and notice that the world around me is more colorful, more beautiful, I’m more inclined to break my infinite scrolling and spend time outside of it.

I still break the rules I’ve made. I turn off the color filter to check out photos I’ve taken; I check social media on my web browser. But, I make it inconvenient to use the phone in a way I don’t want to be using it. My time spent on the small screen is steadily decreasing, and I try to find more productive ways to cope than filling my brain with infinite content.

I don’t know what world I’m living in now. But, I’ve noticed that my world leans on the screen less than it did before. I have time and desire to read, write, draw, relax, and be bored. I care about how my body feels. And I imagine a new world where my phone will die and I won’t immediately abandon my life to charge it.