by David Kordahl

The physicist Philip W. Anderson, winner of the Nobel Prize in 1977, has lingered in the broader scientific imagination for two main reasons—reasons, depending on your vantage, that cast him either as a hero, or as a villain.

The heroic Anderson is the author of “More Is Different,” the 1972 essay that wittily dismisses the idea that the laws of physics governing the microscopic constituents of matter are by themselves enough to capture the full richness of the world. His vision of science as a “seamless web” of interconnections led to his becoming one of the public faces of so-called “complexity science,” and a founding member of the Santa Fe Institute.

The villainous Anderson is remembered for taking this position—the position that the low-level laws of physics do not exhaust fundamental physics—in front of Congress. Anderson’s tart exchanges with Steven Weinberg before the Senate debating the merits of the Superconducting Super Collider (SSC) begin a new biography, A Mind Over Matter: Philip Anderson and the Physics of the Very Many, by Andrew Zangwill. When the SSC was canceled, Anderson, who argued that the funds would be better spent on a wider variety of projects, became a target of physicists’ ire, despite his lack of any significant political influence. (Weinberg’s last book of essays, which I reviewed, extensively discussed the politics of the SSC.)

But Anderson, who died just last year, was much more than just a hero or villain. A Mind Over Matter makes the case that Anderson was “one of the of the most accomplished and influential physicists of the twentieth century.” In presenting the evidence, Zangwill, who is himself a notable physicist, gives us a tour of condensed-matter physics, the science that deals with the properties of materials not atom-by-atom but roughly 1023 particles at a time, a subject where Anderson’s influence continues on. Read more »

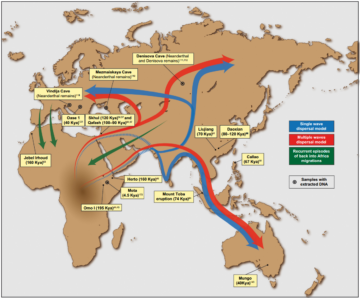

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors  hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter.

hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter. Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?  It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.

It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.

At MIT I had my initiation into a breathless pace of academic activity that was quite different from the pace I had seen elsewhere until then. The whole place was a dynamo of research activity, you could almost hear the hum and feel the energetic throb of multiple high-powered brains at work. While teaching was an important part of daily activity and it often fed into research, it was research where the main action was. Later I found out this was more or less the case in other top departments in the country, but at MIT I had my first experience. There was the thrill of thriving at the frontier of your subject, you saw the frontier visibly moving from one seminar to another, from one widely-cited journal article to another, you had to run fast even to remain at the same place, and while the competition and the race were invigorating, you could also see the jostling and the occasional hustle.

At MIT I had my initiation into a breathless pace of academic activity that was quite different from the pace I had seen elsewhere until then. The whole place was a dynamo of research activity, you could almost hear the hum and feel the energetic throb of multiple high-powered brains at work. While teaching was an important part of daily activity and it often fed into research, it was research where the main action was. Later I found out this was more or less the case in other top departments in the country, but at MIT I had my first experience. There was the thrill of thriving at the frontier of your subject, you saw the frontier visibly moving from one seminar to another, from one widely-cited journal article to another, you had to run fast even to remain at the same place, and while the competition and the race were invigorating, you could also see the jostling and the occasional hustle. Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom.

Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom. My immediate thought after finding out that he had won this ultimate literary accolade was that it couldn’t have happened to a nicer or more grounded writer. In a

My immediate thought after finding out that he had won this ultimate literary accolade was that it couldn’t have happened to a nicer or more grounded writer. In a

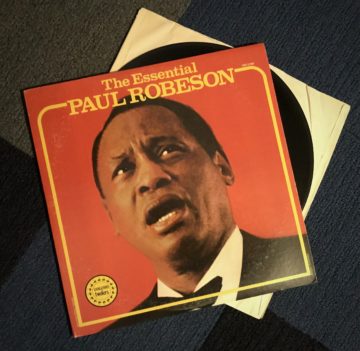

A few years ago, there was a debate in the pages of a British newspaper along the lines of ‘is Keats better than Bob Dylan?’. Mainly futile, I think, as the unanswered question was surely better at what? It’s not clear that one can usefully compare -and rank -an early 19th century lyric poet with a 20th/21st singer-songwriter, because they aren’t really doing the same thing. Another half submerged question lurking in the discussion, was really: are there standards by which we can assess the excellence or otherwise of a work of art? Is there is a qualitative difference between the novels of Tolstoy and those of Dan Brown – or should we just say, ‘if you like it, it’s as good as anything else’? Here, I think, the discussion often gets confused. So we have a debate about excellence, or worth, judged according to an uncertain standard; and conflated with that another about the canon, about ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, so called. Here you might well be tempted to dismiss it all, and just say ‘if I like it, its enough’, or maybe better: ‘there are no standards beyond ones own taste’. If that is so, we might as well just shut up about what we like or don’t like in art. A person just has the response they happen to have, and different people will have different responses. The rest is, or should be, silence.

A few years ago, there was a debate in the pages of a British newspaper along the lines of ‘is Keats better than Bob Dylan?’. Mainly futile, I think, as the unanswered question was surely better at what? It’s not clear that one can usefully compare -and rank -an early 19th century lyric poet with a 20th/21st singer-songwriter, because they aren’t really doing the same thing. Another half submerged question lurking in the discussion, was really: are there standards by which we can assess the excellence or otherwise of a work of art? Is there is a qualitative difference between the novels of Tolstoy and those of Dan Brown – or should we just say, ‘if you like it, it’s as good as anything else’? Here, I think, the discussion often gets confused. So we have a debate about excellence, or worth, judged according to an uncertain standard; and conflated with that another about the canon, about ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, so called. Here you might well be tempted to dismiss it all, and just say ‘if I like it, its enough’, or maybe better: ‘there are no standards beyond ones own taste’. If that is so, we might as well just shut up about what we like or don’t like in art. A person just has the response they happen to have, and different people will have different responses. The rest is, or should be, silence.

Sughra Raza. Starry Night, October 2021.

Sughra Raza. Starry Night, October 2021.