by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

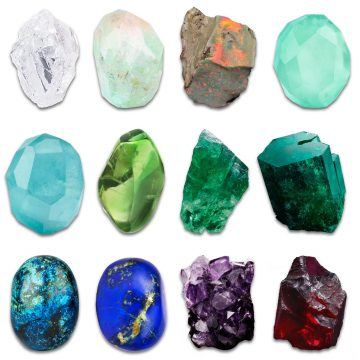

Gems carry a lure that is quintessentially primeval. Considered valuable throughout human history for obvious reasons such as rarity, durability and beauty, gems are inextricable not only from lore, art, architecture, culture, and craft, but also the aesthetics of language. Stories of different civilizations come to us carved in gemstones— Jade figurines of the Forbidden City in Beijing, lapis funerary masks of ancient Egypt, amber encrusted palaces in Moscow, the fabled and famously fought over “koh-i-noor” diamond, the emerald cups and diamond candlesticks of the Ottomans, the bejeweled “peacock throne,” the rubies of Ceylon— and stories manifold to these in words, from myths passed down via the oral tradition, to scripture, fairy tales, poetry and actual accounts of history, to science talk of archeology and gemology.

Gems carry a lure that is quintessentially primeval. Considered valuable throughout human history for obvious reasons such as rarity, durability and beauty, gems are inextricable not only from lore, art, architecture, culture, and craft, but also the aesthetics of language. Stories of different civilizations come to us carved in gemstones— Jade figurines of the Forbidden City in Beijing, lapis funerary masks of ancient Egypt, amber encrusted palaces in Moscow, the fabled and famously fought over “koh-i-noor” diamond, the emerald cups and diamond candlesticks of the Ottomans, the bejeweled “peacock throne,” the rubies of Ceylon— and stories manifold to these in words, from myths passed down via the oral tradition, to scripture, fairy tales, poetry and actual accounts of history, to science talk of archeology and gemology.

The seventeenth century Flemish chronicler and diamond dealer Jacques de Coutre describes the Mughal emperor Jahangir as “looking like an idol on account of the quantities of jewels he wore, with many precious stones around his neck as well as spinels, emeralds and pearls on his arms, and diamonds hanging from his turban.” While some are attracted to gems as symbols of power and wealth, and others as the source of wellness energy, adornment or materials for craft, poets, artisans and artists have developed a complex vocabulary around gems through the millennia and across cultures. Vermeer brings out the unique luster of a pearl, in “The Girl with the pearl Earring,” the mosque-builders of Samarkand make an epic out of turquoise, Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato uses the most precious pigment available— derived from lapis lazuli— to paint the richest, most vibrant blue mantle in “The Virgin in Prayer,” the Mughals build the Taj Mahal, an architectural marvel of gem-inlay and marble.

Writers throughout history have attempted to make accurate descriptions of the play of color and light in different gems. Of opals, Pliny writes: “There is in them a softer fire than the ruby, there is the brilliant purple of the amethyst, and the sea green of the emerald – all shining together in incredible union. Some by their splendor rival the colors of the painters, others the flame of burning sulphur or of fire quickened by oil.”

The language around gems is at once bound to the perception their physicality evokes, and transcends it. The gradation and intensity of color, shine, and the flickering of light is closely studied by poets not only for the senses they stimulate but the spectrum of emotion and the metaphoric imagination they generate. The bard uses the iridescence and changeable sheen of the opal as a metaphor for fickleness in these lines from Twelfth Night:

“Now the melancholy god protect thee; and the tailor make thy

doublet of changeable taffeta, for thy mind is a very opal!”

Emily Dickinson imagines the light of rubies in heaven:

“I went to heaven,–

‘T was a small town,

Lit with a ruby,

Lathed with down.

Stiller than the fields

At the full dew,

Beautiful as pictures

No man drew. “

Classical Persian poets use images of corals and pearls to describe the beloved’s beauty, and numerous colors as similes. Colors are identified in many languages stand-ins for gems, such as ruby, sapphire or pearl. The naming of shades of color is the marriage of language with a somewhat historically continuous, unbroken associative logic, often steeped in culture and distilled as symbol. “Lajward” or Lapis in Persian is used to describe the sky in Urdu poetry—it is the ultramarine of the heavens in the best known Renaissance art. A symbol of eternity for ancient Egyptians, Lapis has survived in artifacts from the ancient Indus valley and Mesopotamia, and mentioned in ancient texts such as Gilgamesh. It is the luxurious blue of Cleopatra’s eye shadow and the gold-specked legend of Badakhshan known to Marco Polo and Alexander the Great, sojourners of the Silk Road.