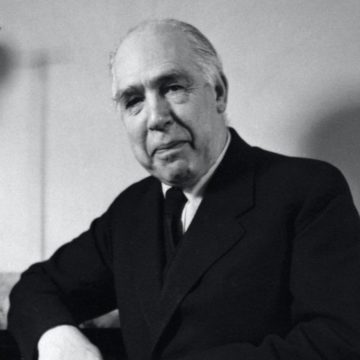

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Werner Heisenberg was on a boat with Niels Bohr and a few friends, shortly after he discovered his famous uncertainty principle in 1927. A bedrock of quantum theory, the principle states that one cannot determine both the velocity and the position of particles like electrons with arbitrary accuracy. Heisenberg’s discovery foretold of an intrinsic opposition between these quantities; better knowledge of one necessarily meant worse knowledge of the other. Talk turned to physics, and after Bohr had described Heisenberg’s seminal insight, one of his friends quipped, “But Niels, this is not really new, you said exactly the same thing ten years ago.”

In fact, Bohr had already convinced Heisenberg that his uncertainty principle was a special case of a more general idea that Bohr had been expounding for some time – a thread of Ariadne that would guide travelers lost through the quantum world; a principle of great and general import named the principle of complementarity.

Complementarity arose naturally for Bohr after the strange discoveries of subatomic particles revealed a world that was fundamentally probabilistic. The positions of subatomic particles could not be assigned with definite certainty but only with statistical odds. This was a complete break with Newtonian classical physics where particles had a definite trajectory, a place in the world order that could be predicted with complete certainty if one had the right measurements and mathematics at hand. In 1925, working at Bohr’s theoretical physics institute in Copenhagen, Heisenberg was Bohr’s most important protégé had invented quantum theory when he was only twenty-four. Two years later came uncertainty; Heisenberg grasped that foundational truth about the physical world when Bohr was away on a skiing trip in Norway and Heisenberg was taking a walk at night in the park behind the institute. Read more »

A scar is a shiny place with a story.

A scar is a shiny place with a story. When I first attended the occasional Harvard-MIT joint faculty seminar I was dazzled by the number of luminaries in the gathering and the very high quality of discussion. Among the younger participants Joe Stiglitz was quite active, and his intensity was evident when I saw Joe chewing his shirt collar, a frequent absent-minded habit of his those days. Sometimes one saw the speaker incessantly interrupted by questions, say from one of the big-name Harvard professors, Wassily Leontief (soon to be a Nobel laureate). At Solow’s prodding I agreed to present a paper at that seminar, with a lot of trepidation, but fortunately Leontief was not present that day.

When I first attended the occasional Harvard-MIT joint faculty seminar I was dazzled by the number of luminaries in the gathering and the very high quality of discussion. Among the younger participants Joe Stiglitz was quite active, and his intensity was evident when I saw Joe chewing his shirt collar, a frequent absent-minded habit of his those days. Sometimes one saw the speaker incessantly interrupted by questions, say from one of the big-name Harvard professors, Wassily Leontief (soon to be a Nobel laureate). At Solow’s prodding I agreed to present a paper at that seminar, with a lot of trepidation, but fortunately Leontief was not present that day.

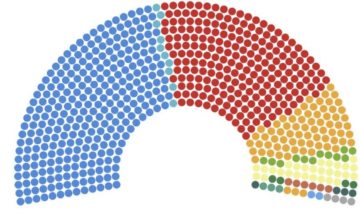

In politics, business, and education, the issue of how to ensure proportional representation of groups is often salient. A salient issue, but usually an impossible task. Why?

In politics, business, and education, the issue of how to ensure proportional representation of groups is often salient. A salient issue, but usually an impossible task. Why?

My books are arranged more or less the way a library keeps its books, by subject and/or author, although I don’t use call numbers. I also have various piles of current and up-next and someday-soon reading. In addition, I have a loose set of idiosyncratic categories that guide my choice of what to read right now, out of several books I’m reading at any given time. I choose books for occasions the way more sociable people choose wines to complement their menus.

My books are arranged more or less the way a library keeps its books, by subject and/or author, although I don’t use call numbers. I also have various piles of current and up-next and someday-soon reading. In addition, I have a loose set of idiosyncratic categories that guide my choice of what to read right now, out of several books I’m reading at any given time. I choose books for occasions the way more sociable people choose wines to complement their menus.