by Eric J. Weiner

D: Well my name is Dick Doolittle and I’m a reporter from Grime magazine and we would like you to comment on the tragic riots—

B: Not a riot, it’s a rebellion

D: Well the tragic rebellion?

B: Man, tragic for who?

D: Well there’s havoc in the streets, the police have lost control over the People, criminals are running free from jail, and people are actually taking property from big businesses, it’s full of complete chaos

B: That’s not chaos, that’s progress

“The Coup,” from the album Kill My Landlord, The Coup

What does it mean to be white in America in 2020?[1] As Boots Riley points out to Dick Doolittle in the opening exchange to the song The Coup, one of the things it means to be white in America is you have the power to define the terms of the debate. In this exchange, the rebellion is cast first as a riot and then a “tragic” rebellion until Boots checks the journalist. As people from across the racial spectrum rebel against police violence and systemic racism, the question, “What does it mean to be white?” is more than a question about unpacking the backpack of white privilege[2]; it requires a detour through the educational, cultural, and political apparatuses of our culture.

What does it mean to be white in America in 2020?[1] As Boots Riley points out to Dick Doolittle in the opening exchange to the song The Coup, one of the things it means to be white in America is you have the power to define the terms of the debate. In this exchange, the rebellion is cast first as a riot and then a “tragic” rebellion until Boots checks the journalist. As people from across the racial spectrum rebel against police violence and systemic racism, the question, “What does it mean to be white?” is more than a question about unpacking the backpack of white privilege[2]; it requires a detour through the educational, cultural, and political apparatuses of our culture.

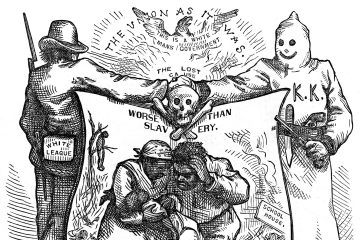

I am white and was educated from K-12 to never question the norms, values, and goals of white supremacy. I am being more than just provocative when I use the term “white supremacy” to describe my education. White supremacy should not be reduced to describing the most extreme forms of hatred and violence leveled against people of color. More inclusively, it is an ideological world view that makes whiteness a universal marker of innocence, excellence, power, beauty, intelligence, and progress. I think it’s important to reclaim the term from the referent of the Ku Klux Klan and other extreme right-wing terrorist groups because it gives us a way to think about the formative historical structures and systems that seed the soil for the emergence of white identity and consciousness in the United States. The construction of white identity is inseparable from its intimate association to the forces of colonization and the domination and exploitation of people of color.

Moreover, as bell hooks explains,

white supremacy is a much more useful term for understanding the complicity of people of color in upholding and maintaining racial hierarchies that do not involve force (i.e., slavery, apartheid) than the term ‘internalized racism’- a term most often used to suggest that black people have absorbed negative feelings and attitudes about blackness. The term ‘white supremacy’ enables us to recognize not only that black people are socialized to embody the values and attitudes of white supremacy, but we can exercise ‘white supremacist control’ over other black people.” [3]

White people—even those protesting against racial injustice—are the primary beneficiaries of our system of white supremacy, although depending upon the degree of “buy-in,” people of color can also be rewarded for their quiet cooperation within the system. Of course, the consequences of buying into the system of white supremacy for white folks versus black folks is quantifiably and qualitatively different and should never be understood as an equivalence. When white folks buy-in they get lifted up. When black folks buy-in, they get pushed down while lifting white folks ever higher. So, another thing it means to be white is to be able reap the benefits of living in a system that values white identity above all other racial identities while never having to acknowledge that any such system exists.

As a white child, from schooling to popular culture, I was taught to not think of myself as a member of a racial group. Indeed, from the liberal perspective of my home and, to some degree, my school, to acknowledge racial differences in terms of experience was considered racist. The appeal to color-blindness is still a liberal strategy (but now used by conservatives as well) of erasure and myth-making that helps bolster the reproduction of white supremacist ideology; it erases whiteness from the history of white racial violence and the domination and exploitation of people of color. By teaching me to ignore my race–that being white isn’t a source of knowledge and meaning–I am let off the hook. When I learned about racism at home and in school, I typically learned about the victims of racial violence and the Civil Rights movement. The schools I attended outside Philadelphia were, with the exception of a few students of color, all white. Until I attended university, I never had a teacher who was a person of color. I was introduced to the Civil Rights work of Dr. King and Rosa Parks. I learned Parks was tired which is why she sat down on the seat in the bus. I learned that black people were once slaves and even after slavery officially ended were sometimes treated unfairly, especially in the South. I learned that because of the civil rights movement, black and white people now enjoy the same opportunities for education and economic mobility. I learned that race doesn’t matter anymore, unless we were discussing jazz music or silently locking the car doors as we approached North Philadelphia on Broad Street from the white northern suburbs of Willow Grove. I learned to love jazz and the black musicians who played it. When African American people struggle in the United States economically or judicially, I was taught that it could have something to do with their culture. But I was never taught that it might have something to do with mine. I learned that there were some racist white people that didn’t like black people. In school, racists were typically represented as residing in “the South,” although there were plenty of racists in Philadelphia too. I was taught to believe that southern white people were dumb. I learned that some racists wore white hoods and capes. They burned crosses. They used the “N-word.” I never did, although some of my friends did. Some racists were cops with vicious dogs. Unlike northern whites like us, they hated black people. These were bad, ignorant white people. We were good, intelligent white people because race didn’t matter to us. I was taught that we are all created equal. I learned to see myself as a human being; not a white human being.

My schooling never addressed the hegemony of white supremacy in the United States and never asked me to think about what it means to be white. The white supremacist education that I received in my elementary and secondary schooling is now part of the “official curriculum”[4] in the United States and takes shape in the form of a kind of liberal multiculturalism in which the history of racism is taught while the continued hegemony of white supremacy is ignored.

Maybe this is why in the midst of all of the recent critical commentary I hear from black folks in the press explaining to the primarily white talk show hosts (and their overwhelmingly white audiences) the complicated realities of black life in America, I haven’t heard a sustained discussion from the perspective of white folks about how well we have learned the values and norms of white supremacy; enjoy the benefits of its relentless reproduction; and use it, consciously or not, as a shield to protect us from our culpability in the continued domination and exploitation of black folks. As James Baldwin, writing to his nephew says, “[White people] are in effect still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it. They have had to believe for many years, and for innumerable reasons, that black men are inferior to white men.”[5] With few exceptions (i.e., Tim Wise), the absence of white folks in the mainstream media explaining our culpability in the death of George Floyd, Eric Garner, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown, Tamir Rice, Jordan Davis, Alton Sterling, Christian Cooper, Philando Castile, Amadou Diallo, Walter Scott, Oscar Grant, Aiyana Jones, and Marquise Jones (among the many other victims of white supremacy that have been lost in the din of white history) speaks volumes about the effectiveness of our white supremacist educational system. It has nurtured a culture of whiteness and silence that is unable, and in many cases unwilling, to grasp the significance of what it means to be white under the regime of white supremacy. It’s like white folks have collectively “taken the 5th” because they know to speak honestly about their experiences of whiteness will incriminate them.

Maybe this is why in the midst of all of the recent critical commentary I hear from black folks in the press explaining to the primarily white talk show hosts (and their overwhelmingly white audiences) the complicated realities of black life in America, I haven’t heard a sustained discussion from the perspective of white folks about how well we have learned the values and norms of white supremacy; enjoy the benefits of its relentless reproduction; and use it, consciously or not, as a shield to protect us from our culpability in the continued domination and exploitation of black folks. As James Baldwin, writing to his nephew says, “[White people] are in effect still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it. They have had to believe for many years, and for innumerable reasons, that black men are inferior to white men.”[5] With few exceptions (i.e., Tim Wise), the absence of white folks in the mainstream media explaining our culpability in the death of George Floyd, Eric Garner, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin, Mike Brown, Tamir Rice, Jordan Davis, Alton Sterling, Christian Cooper, Philando Castile, Amadou Diallo, Walter Scott, Oscar Grant, Aiyana Jones, and Marquise Jones (among the many other victims of white supremacy that have been lost in the din of white history) speaks volumes about the effectiveness of our white supremacist educational system. It has nurtured a culture of whiteness and silence that is unable, and in many cases unwilling, to grasp the significance of what it means to be white under the regime of white supremacy. It’s like white folks have collectively “taken the 5th” because they know to speak honestly about their experiences of whiteness will incriminate them.

“What does it mean to be white?” is a hard question for many white people to answer as we have been taught to think of ourselves as humans and not as being from a particular race of people. As Victor Lewis says in the film The Color of Fear, for white people in America “human,” “white,” and “American” are synonyms.[6] As such, we are rarely if ever forced to think about what it means to be white because our experiences as white people are erased under an appeal to universality. The very fact that the question is rarely posed or ever considered is just another example of how white supremacy informs our understanding of racism in America. Racism, as Victor explains, is essentially a white problem. People of color bear the brunt of the problem, but they are not the problem. The mis-education of white folks about what it means to be white is a central problem for any movement of racial and economic justice. Until we can rethink how we critically educate ourselves about our racial group, shared history, and continued culpability in the reproduction of white supremacy, I don’t believe we will see a change in the regime. For a regime change to occur, we will need to experience a form of psychic pain and corporeal discomfort; a level of existential chaos that radically transforms our bodies and minds. James Baldwin gets at the core of what we will have to contend with if we are truly committed to destroying the regime of white supremacy in the United States:

Try to imagine how you would feel if you woke up one morning to find the sun shivering and all the stars aflame. You would be frightened because it is out of the order of nature. Any upheaval in the universe is terrifying because it so profoundly attacks one’s sense of one’s own reality. Well, the black man has functioned in the white man’s world as a fixed star, as an immovable pillar, and as he moves out of his place, heaven and earth are shaken to their foundations.[7]

As white people, we cannot remain as we have been and expect the structures of white supremacy to magically disappear. Nothing less than a complete undoing of white identity and consciousness as its been constructed since at least the 15th century will suffice if we truly want to end the hegemony of white supremacy in the United States. This undoing, is in large part, a question and challenge for education.

But let’s be clear about what kind of education is required. However important it is for me to learn from black folks about what it means to be African American under the regime of white supremacy, it is just as important for me to educate myself and my white brothers and sisters as to what it means to be living as a white person under that same regime. It cannot be the sole responsibility of black folks to educate us about our experiences of power and privilege under the regime of white supremacy. We must use our time and resources, many of which are a direct outcome of living as white folks within the context of white supremacy, to critically educate ourselves about what it means to be white. It seems to be just another example of white privilege (which is the outcome of sustained white violence and domination over people of color) to assume that people of color will have the time and inclination to educate us about our past and present. To expect this or, even worse, demand it, is a racist cliché turned pedagogical strategy; that is, the enlightened and wise African American teacher patiently teaching the skeptical white student about what it means to be white. This often involves, on the part of the teacher of color, divulging painful experiences in an effort to get white folks to care about the plight of black folks while learning about their own savage history. At which point, the unseeing, unknowing, and willfully ignorant white person often sees fit to cross-examine the person of color and her account of white supremacy (another example of what it means to be white within the ideology of white supremacy). This is an unfair burden to put on people who are already being pushed to the breaking point. And, frankly, there is no reason why people of color should trust that white people are truly committed to the destruction of white supremacy. Marching in rallies and carrying signs is important, but, as Victor Lewis (Color of Fear) says, until we are willing to be transformed by the black experience as much as they are constantly shaped, twisted and turned upside down by ours, there is little reason for them to trust us.[8]

Public schools in the United States do not teach students to think critically about the legacy and hegemony of white supremacy. By mis-educating white (and black) children about racism through an abbreviated, sanitized, and whitewashed curriculum about the Civil Rights movement and slavery, schools help to reproduce white supremacist ideology; by ignoring, rationalizing, normalizing, and/or erasing what it means to be white in America, we are mis-educating white folks about their history and how the current racial hierarchies of powers impact everyday life. For an example of how white supremacy informs school curriculum and culture, just go into any school and library during the month of February. Posters, lectures, projects and poems will be the focus of learning and teaching as schools celebrate “black history month.” For advocates of this type of liberal multicultural curriculum, the celebration of black history month is evidence that the curriculum is not racist and certainly not an articulation of white supremacy. But, of course, the reality is the exact opposite; the existence of “black history month” is evidence of a curricular alignment with white supremacist ideology because it allows whiteness to remain invisible, normative, a referent for human history, and a sign of innocence. As James Baldwin writes, “…it is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.”[9]

To put a finer point on the criticism of how education supports the system of white supremacy, both white and black students are denied a form of education that exposes the formidable role of white supremacy in the building of the nation, the formation of its government, the design of its schools, the building of its cities, the maintenance of its economy, the form/function of its judiciary, the policing of its borders and people, and the delivering of its healthcare. Education matters, but not all education offers students the opportunity to think critically about how white identity is connected intimately to racial and economic injustice in America. All of the major architects of the aforementioned sectors in which white supremacist ideology reigns went to the “best” primary and secondary schools and the most exclusive colleges and universities. Many even went on to get advanced degrees in law, medicine, business, and education. I am sure they learned about the Civil Rights movement and the horror and violence of racism. But an education that hopes to destroy white supremacist ideology cannot continue to ignore the legacy of oppression that has informed the construction of white identity and consciousness.

In our public and many of our private schools, we continue to teach white folks that their experiences in America are the same as black folks; this signals a crisis in what C. Wright Mills called the “sociological imagination.” White people are rarely asked to think about their successes as connected to social systems and structures, just as black folks are discouraged from thinking about their personal struggles as public issues. In both instances, black and white folks are left with no way to think critically about their relationship to formations of knowledge and power; the inequitable distribution of resources that gives teeth to the axiom of choice; and the educational cleavages that help sustain what Thomas Picketty calls “inequality regimes.”[10] The difference is that white folks benefit from the crisis; we learn that our successes are due to hard work, exceptional genes, good family structure, and moral behavior. We learn that everyone, regardless of race, has an equal opportunity. It then follows that those who don’t have our success must be operating at a personal or cultural deficit. For black folks, the crisis is more pernicious; without a sociological imagination, black folks are likely to internalize white supremacist ideas about the inferiority of black culture, history and knowledge. “Please try to remember,” Baldwin tells his nephew, “that what they believe, as well as what they do and cause you to endure, does not testify to your inferiority, but to their inhumanity and fear.”[11]

What is at the heart of the kind of education I received versus the kind of education most black folks receive, is a powerful sense of my own agency; I learned to believe I could do almost anything for no other reason than my race and gender. I was born into a working, middle-class community with a clean, safe, and well-equipped public school and taught by teachers who were members of my racial group. All of the other kids in the school, with the exception of one or two, were white like me. It was assumed that the future I faced was full of hope and possibility for no other reason than my race. There were few limits placed upon my ambitions and my worth as a human being was never questioned. I was expected to aspire to excellence and look upon mediocrity as a sign of failure. I was rarely told where I could go, what I could do, how I could do it, and where I could live and whom I could marry. Compare my experience as a white person with James Baldwin’s counsel to his nephew:

This innocent country set you down in a ghetto in which, in fact, it intended that you should perish…You were born where you were born and faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason. The limits to your ambition were thus expected to be settled. You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity and in as many ways as possible that you were a worthless human being. You were not expected to aspire to excellence. You were expected to make peace with mediocrity. Wherever you have turned, James, in your short time on this earth, you have been told where you could go and what you could do and how you could do it, where you could live and whom you could marry.[12]

Part of the challenge of teaching white folks to think critically about white identity in the hopes of destroying the hegemony of white supremacy requires some consistency and coherence from teachers and administrators across the grades. We might start by forming curriculum and lessons that focus on some hard, historical truths. For example, as Time Wise writes, “We are here because of blood, and mostly that of others. We are here because of our insatiable desire to take by force the land and labor of others.”[13] By “here” he, of course, is referring to white folks being at the top of all the major institutions of power. A curriculum and pedagogy of this nature would be a challenge to the ongoing myth of Manifest Destiny, reasserted recently and symbolically by Trump who held up a bible in front of St. John’s Church in Washington, DC after directing the police to forcefully remove people who were peacefully rebelling against police violence and white supremacy.

We might then design age-appropriate learning projects that bring attention to how, as Tim Wise writes:

the ‘ghettos’ in our country were created, and not by the people who live in them. They were designed as holding pens — concentration camps were we to insist upon plain language — within which impoverished persons of color would be contained. Generations of housing discrimination created them, as did decade after decade of white riots against black people whenever they would move into white neighborhoods. They were created by deindustrialization and the flight of good-paying manufacturing jobs overseas.[14]

The deafening silence emanating from white folks regarding what it means to be white under the regime of white supremacy must end. For people of color, as Audre Lorde famously counseled, “Your silence will not protect you.” But the same cannot be said for white folks. Our silence does protect us just as it continues to leave untroubled our culpability in the violence and exploitation being done to people of color. Raising our voices and fists in solidarity is only part of the critical educational project. The other part must entail a reckoning with history and the entangled legacies of whiteness and white supremacy in the development and evolution of American society. Until we (white folks) commit to taking responsibility for critically educating ourselves and each other about white identity and consciousness–until we commit ourselves to the critical educational project of unlearning–the system of domination and privilege called white supremacy will continue to allow for peaceful protests, multicultural education, and white guilt, while leaving in place hierarchies of power that degrade, exploit, and dehumanize people of color. James Baldwin wrote that “to act is to be committed and to be committed is to be in danger.” Are white people prepared to place themselves in danger? One of the things it means to be white in America is we get to choose.

[1] I will not address the issue of intersectionality in this discussion. My comments will be focused upon the issue of race and white supremacy. While I understand that we experience racial issues differently depending on our class, gender, and sexuality, I think it is vital that the issue of white supremacy is addressed as directly as possible and without distraction. In the final analysis, which this is not, I think bell hooks is correct when she describes our current system as an interlocking system of domination made up essentially of white supremacy-capitalism-patriarchy and as such represents a complex web of differential experiences. But intersectionality, I believe can also be deployed as a distraction, particularly by liberal white people who, in my experience, would like to talk about almost anything—gender, sexuality even class—before engaging in a critical analysis of white identity construction, white supremacy, and questions of culpability and privilege.

[2] See Peggy McIntosh, White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. https://www.racialequitytools.org/resourcefiles/mcintosh.pdf

[3] bell hooks. 1999. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. Boston: South End Press.

[4] Michael W. Apple (1993) The Politics of Official Knowledge: Does a National Curriculum Make Sense?, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 14:1, 1 16, DOI: 10.1080/0159630930140101

[5] James Baldwin. 1962. A Letter to m My Nephew. https://progressive.org/magazine/letter-nephew/

[6] Color of Fear. 1994. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0484384/

[7] James Baldwin, ibid.

[8] See clip. https://youtu.be/2nmhAJYxFT4

[9] James Baldwin, ibid.

[10] Thomas Piketty. 2020. Capital and Ideology. Trans. Arthur Goldhammer, Boston, U.S.A: Harvard University Press.

[11] James Baldwin, ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Tim Wise. 2020. Protest, Uprisings and Race War reposted in: https://3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2020/05/protest-uprisings-and-race-war.html

[14] Ibid.