by Rafaël Newman

Neapolitan conversation is impenetrable to outsiders. Ears, nose, eyes, breast and armpits are signal stations to be pressed into use by fingers, a distribution that recurs in the particular specializations of the local erotics. The foreigner is struck by so much solicitous gesturing and impatient touching, whose regularity rules out coincidence. And while the Neapolitan may betray him, even sell him out—yet in the end he bids the foreigner a good-humored addio: sends him on his way, a few kilometers down the road to the village of Mori. Vedere Napoli e poi Mori, says the Neapolitan, reciting an old joke. “See Naples and die,” echoes the German. —Walter Benjamin and Asja Lācis1

“The German,” among other foreigners, may perhaps be forgiven for reflexively associating Naples with death. There is the archaic quality of the city’s public superstition, present in the phallic horns everywhere for sale, said to be useful in warding off the fatal Evil Eye. There is the enormous hexagonal pile of the Castel Sant’Elmo looming over the city, its blank medieval walls threatening would-be invaders with doom; and there is its equally brooding partner on the harbor front, the Castel dell’Ovo, built, legend has it, upon a hidden Virgilian egg, whose fragile intactness is the only guarantee of the fortification’s survival. Just a little further afield, and ever present on the horizon, watching over all the many and varied rituals of daily life, is the sinisterly mammary double hulk of Vesuvius, mainland Europe’s only recently active volcano, an ominously smoking reminder, via the nearby ghost towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, of a capricious and death-dealing nature. (Naples itself lies athwart the Phlegraean Fields, an area of volcanic activity under continuous seismographic surveillance.) And, shot through the entire place, invisible to the untrained eye save in the ubiquitous mounds of ostentatiously uncollected garbage, there is the loosely organized criminal society known as the Camorra, whose provision—or repression—of communal services, and whose targeted acts of violence to enforce its rule, have been mortally endangering the health of Neapolitans for centuries.

Walter Benjamin and Asja Lācis, in their 1925 essay on Neapolitan architecture, were unexpectedly downbeat about the city’s physical aspect, which, they maintained, does not provide the Mediterranean charm and balm for the eyes expected by the routine northern visitor: “Fantastical travelogues have colorized the city; in reality it is gray, a grayish red or ochre, a grayish white. And quite completely gray where it meets the sky and sea. This is not the least of the reasons for its citizens’ anhedonia. For if one has no eye for shapes, there is little to see here. The city is craggy. Seen from the heights, where the voices are unheard, from Castell San Martino, it lies extinct in the twilight, petrified.”2 And indeed, for all their vividness, the visual arts, as generously on display in Naples as in many other Italian cities, offer no more respite from this general air of memento mori (by which I do not mean a souvenir stand in the notorious neighboring village) than does its architecture. Read more »

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?  It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.

It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.

At MIT I had my initiation into a breathless pace of academic activity that was quite different from the pace I had seen elsewhere until then. The whole place was a dynamo of research activity, you could almost hear the hum and feel the energetic throb of multiple high-powered brains at work. While teaching was an important part of daily activity and it often fed into research, it was research where the main action was. Later I found out this was more or less the case in other top departments in the country, but at MIT I had my first experience. There was the thrill of thriving at the frontier of your subject, you saw the frontier visibly moving from one seminar to another, from one widely-cited journal article to another, you had to run fast even to remain at the same place, and while the competition and the race were invigorating, you could also see the jostling and the occasional hustle.

At MIT I had my initiation into a breathless pace of academic activity that was quite different from the pace I had seen elsewhere until then. The whole place was a dynamo of research activity, you could almost hear the hum and feel the energetic throb of multiple high-powered brains at work. While teaching was an important part of daily activity and it often fed into research, it was research where the main action was. Later I found out this was more or less the case in other top departments in the country, but at MIT I had my first experience. There was the thrill of thriving at the frontier of your subject, you saw the frontier visibly moving from one seminar to another, from one widely-cited journal article to another, you had to run fast even to remain at the same place, and while the competition and the race were invigorating, you could also see the jostling and the occasional hustle. Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom.

Philosophy, as we teach it in the U.S. and Europe, originated in Ancient Greece, specifically in the person of Socrates who wandered the marketplace tormenting fellow citizens with incessant questions and losing his life for his efforts. For Socrates, there was one overriding question that not only defined philosophy and distinguished it from other inquiries but was a question all human beings should urgently and persistently ask. What is the best life for human beings? His answer was that only a life in pursuit of wisdom regarding what is good could be fully satisfying and complete. The implication was that philosophy was not only a way of life but the best form of life possible since it was uniquely the job of philosophy to discover wisdom. My immediate thought after finding out that he had won this ultimate literary accolade was that it couldn’t have happened to a nicer or more grounded writer. In a

My immediate thought after finding out that he had won this ultimate literary accolade was that it couldn’t have happened to a nicer or more grounded writer. In a

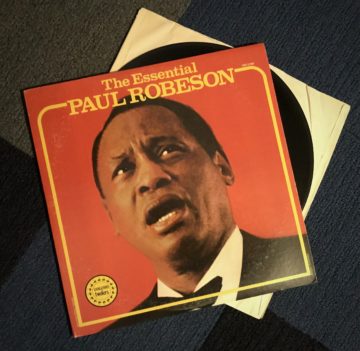

A few years ago, there was a debate in the pages of a British newspaper along the lines of ‘is Keats better than Bob Dylan?’. Mainly futile, I think, as the unanswered question was surely better at what? It’s not clear that one can usefully compare -and rank -an early 19th century lyric poet with a 20th/21st singer-songwriter, because they aren’t really doing the same thing. Another half submerged question lurking in the discussion, was really: are there standards by which we can assess the excellence or otherwise of a work of art? Is there is a qualitative difference between the novels of Tolstoy and those of Dan Brown – or should we just say, ‘if you like it, it’s as good as anything else’? Here, I think, the discussion often gets confused. So we have a debate about excellence, or worth, judged according to an uncertain standard; and conflated with that another about the canon, about ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, so called. Here you might well be tempted to dismiss it all, and just say ‘if I like it, its enough’, or maybe better: ‘there are no standards beyond ones own taste’. If that is so, we might as well just shut up about what we like or don’t like in art. A person just has the response they happen to have, and different people will have different responses. The rest is, or should be, silence.

A few years ago, there was a debate in the pages of a British newspaper along the lines of ‘is Keats better than Bob Dylan?’. Mainly futile, I think, as the unanswered question was surely better at what? It’s not clear that one can usefully compare -and rank -an early 19th century lyric poet with a 20th/21st singer-songwriter, because they aren’t really doing the same thing. Another half submerged question lurking in the discussion, was really: are there standards by which we can assess the excellence or otherwise of a work of art? Is there is a qualitative difference between the novels of Tolstoy and those of Dan Brown – or should we just say, ‘if you like it, it’s as good as anything else’? Here, I think, the discussion often gets confused. So we have a debate about excellence, or worth, judged according to an uncertain standard; and conflated with that another about the canon, about ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, so called. Here you might well be tempted to dismiss it all, and just say ‘if I like it, its enough’, or maybe better: ‘there are no standards beyond ones own taste’. If that is so, we might as well just shut up about what we like or don’t like in art. A person just has the response they happen to have, and different people will have different responses. The rest is, or should be, silence.

Sughra Raza. Starry Night, October 2021.

Sughra Raza. Starry Night, October 2021.

The soon-to-be famous ship is part-way around the world. It will eventually become only the second vessel in recorded history to achieve the complete circumnavigation – after Magellan. But the ship is poised over disaster. Somewhere in the seas off present-day Indonesia, the captain has ordered full sail and then retired to his cabin. The ship hits something – there’s an awful shudder and it stops dead in the water. A reef, probably.

The soon-to-be famous ship is part-way around the world. It will eventually become only the second vessel in recorded history to achieve the complete circumnavigation – after Magellan. But the ship is poised over disaster. Somewhere in the seas off present-day Indonesia, the captain has ordered full sail and then retired to his cabin. The ship hits something – there’s an awful shudder and it stops dead in the water. A reef, probably.