by Charlie Huenemann

In thinking about knowledge and consciousness, it is just about irresistible to distinguish between the basic facts of what we observe and interpretations or beliefs about those facts. You and I see the same glass of water – maybe our perceptions of the glass are nearly identical – and yet you see it has half full while I see it as half empty. We look at the same economic reports, and you find reason to celebrate while I find cause to worry. We see an artificial satellite in orbit, and you see it an incursion of government and industry into space while I see it as a glory of science and engineering. And so on – it seems obvious that there is a divide between what everyone can plainly see and what’s a matter of interpretation.

In thinking about knowledge and consciousness, it is just about irresistible to distinguish between the basic facts of what we observe and interpretations or beliefs about those facts. You and I see the same glass of water – maybe our perceptions of the glass are nearly identical – and yet you see it has half full while I see it as half empty. We look at the same economic reports, and you find reason to celebrate while I find cause to worry. We see an artificial satellite in orbit, and you see it an incursion of government and industry into space while I see it as a glory of science and engineering. And so on – it seems obvious that there is a divide between what everyone can plainly see and what’s a matter of interpretation.

Descartes was scrupulous about this distinction as he inched his way through the Meditations, continually asking himself what he was really experiencing, as opposed to the judgments he was making about the experience. Do I experience my hands? Or do I only experience the visual and tactile data suggesting that I have hands? Can I infer the existence of the material world from what I experience, or are there other ways of interpreting the sensations that do not suppose there is an external world? Evil genius, anyone? Brain in a vat?

It’s this line of thought that led some philosophers to postulate sense data, or private mental packets of experience whose esse is their percipi, meaning that they don’t exist as anything other than sensations. You see the flower in the vase; I do too, but since I’m across the table from you, my sensations are different in some ways. The colors are the same, or close to the same, but the arrangement is different because of our different perspectives. Different perspectives yield different sets of sense data; that’s what makes them different perspectives.

Sense data, so it is claimed, provide the foundation for the judgments we make about experience. The sense data are provided to us like slides on a screen (with smells and tastes and tactile qualities as well), and it is on the basis of these data that we make all sorts of judgments and inferences about what is happening, what has happened, and what will happen next. The data are given (that’s what “data” means); what we do with the given is up to us.

But the problem with sense data is that they don’t exist. Here are a couple of reasons for being suspicious of them. First, there isn’t any empirical evidence of them whatsoever, apart from our thinking that they exist. (This is the downside of having your esse be percipi.) There’s no scientific instrument that can register the presence or absence of a sensation. We can measure the electrical activity of somebody’s brain, of course, and we can watch their pupils dilate, but the only way to find out whether they are experiencing anything is to ask them, and take their word for it. This is the so-called “hard” problem of consciousness: namely, to explain why there should be any consciousness, when nothing we can see “from the outside” gives us any information about it, or indeed any evidence of its existence.

A second reason for being skeptical about sense data there is no way to learn how to speak correctly about them. I can teach a child how to talk about flowers and stones: I say stuff, point, ask questions, hear what they say, correct their answers, etc. But I can’t do this with their sense data, because I can’t point to the data (whether theirs or my own), I can’t judge if they’ve gotten it right, I don’t know when to correct them, etc.

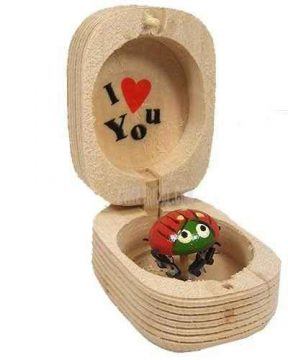

Wittgenstein is the guy who pointed this out with many cunning examples, but the most charming one was the beetle box:

If I say of myself that it is only from my own case that I know what the word “pain” means – must I not say the same of other people too? And how can I generalize the one case so irresponsibly?

Now someone tells me that he knows what pain is only from his own case!

— Suppose everyone had a box with something in it: we call it a “beetle”. No one can look into anyone else’s box, and everyone says he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle.

— Here it would be quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box. One might even imagine such a thing constantly changing.

— But suppose the word “beetle” had a use in these people’s language?

— If so it would not be used as the name of a thing. The thing in the box has no place in the language-game at all; not even as a something: for the box might even be empty.

— No, one can ‘divide through’ by the thing in the box; it cancels out, whatever it is.

(Philosophical Investigations, section 293)

There is the characteristic and delightful back-and-forth in this passage, but Wittgenstein’s overall point is that private stuff can’t make its way into a natural language, since there’s no way to teach someone how to talk about it. Whatever the hell is in the box, it can’t possibly make any difference to what we say about it.

Now this second reason might seem a bit too tidy. After all, here we are, more than 800 words in, talking about stuff that can’t possibly be talked about. (Welcome to philosophy!) So what’s going on?

Well, even if what’s in our beetle boxes doesn’t exist, what we say about what’s in our boxes most certainly does exist. (Bear with me on this.) What we are likely to say about our own experience is shaped by many things: the language we’ve learned, the communities we’re in, the particular occasion we are facing, what we want others to do or believe, and the great many examples we have of what others have said about their experience.

For example, we learn over time that it’s okay to say, “I’m having that same headache again!” but it’s generally not okay to say, “That same headache was in line at the gas station today”. (Except metaphorically, as when we mean that the same annoying person, the one who gives anyone a headache, was in line again; but we had to learn how to make such clever metaphors, and how to recognize the occasions when we can get away with them.) So there is much more going into the reports of our experience than just gazing into a beetle box and reporting what’s there: there’s a great network of language and customs directing the constructions of those reports.

If this is so, then reports of our own experiences – reports of our so-called “sense data” – are every bit as interpretive as the interpretations we have of them. When we try to soberly report on our perceptions of our hands, of the glass containing liquid, of the numerical aspects of the economic reports, and so on, we are busily interpreting the world. We are putting forward judgments about what we experience, and those judgments are shaped by a host of factors other than merely “what we see when we look inside”.

This might sound like a philosophical nicety, but it becomes critically important when it comes to eyewitness testimony. “Just tell us what you saw, sir,” instructs the detective. But what I saw was being heavily influenced by my background assumptions, my prejudices, the stress of the moment, conjectures about what (I think) typically happens in events like this. For such reasons, eyewitness testimony is notoriously unreliable, even if jurors tend to value it above all else.

What we would love to have on hand in such a case is some “brain-o-scope” that could get at the sense data that really were seen, without the distortions of all these interpretive factors. (Sometimes in movies hypnosis is used to get at the ur-data.) But – and this is my point – there can be no such “brain-o-scope” because the stuff it would be looking for does not exist: our perceptions themselves are interpretive judgments. There is no raw data upon which we are making judgments; the judgments are the raw data. If anything, the “raw data” – or the facts – are constructed later on out of the messy mass of judgments people make about their experience, as a kind of least common denominator of various observers’ various judgments.

If this view is true, it helps to make the “hard” problem of consciousness a little easier. For there’s no way to explain how a brain can produce something – a sense datum – that no other measuring device can detect. That’s just an impossible task. But plenty of machines, including brains, can issue interpretive judgments about what’s going on in the environment. Understanding how this happens isn’t easy, of course; but it’s a tractable problem, and not as impossible as the “hard” problem is said to be. Sometimes progress with a problem requires rejecting what seems most obvious: like “what everyone can plainly see”.

(BBC Radio 4 made a short and entertaining video about the beetle-in-the-box analogy, which you can view here. Script by Nigel Warburton.)