by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Though I decided to go back to India, which institution I’d join there took some more time to determine. I had a standing invitation from K.N. Raj at the Delhi School of Economics. Even before I left MIT he asked me to teach a course in MIT’s summer-vacation period. I went and taught part of a course, which had good students (including Amitava Bose, who in his later professional life became close to me, served as a Director of the Indian Institute of Management in Kolkata, and finally lost his long battle against cancer). But I soon found out that the only job Raj could offer me was that of a Readership (Associate Professorship), as a full Professorship was not yet vacant. Amartya-da advised me against accepting a Readership, since in Indian universities there could be ‘many a slip’ even when a Professorship became vacant. I went back to MIT after the vacation, and soon after I got a message from T.N. Srinivasan of the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) in Delhi, offering a full Professorship there, which I accepted.

Though I decided to go back to India, which institution I’d join there took some more time to determine. I had a standing invitation from K.N. Raj at the Delhi School of Economics. Even before I left MIT he asked me to teach a course in MIT’s summer-vacation period. I went and taught part of a course, which had good students (including Amitava Bose, who in his later professional life became close to me, served as a Director of the Indian Institute of Management in Kolkata, and finally lost his long battle against cancer). But I soon found out that the only job Raj could offer me was that of a Readership (Associate Professorship), as a full Professorship was not yet vacant. Amartya-da advised me against accepting a Readership, since in Indian universities there could be ‘many a slip’ even when a Professorship became vacant. I went back to MIT after the vacation, and soon after I got a message from T.N. Srinivasan of the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) in Delhi, offering a full Professorship there, which I accepted.

I was somewhat familiar with the Kolkata headquarters of ISI, a world-class center for statistics those days, with a leafy campus, but I did not know much about the Planning Unit of ISI in Delhi where I was to work. It did not have a campus at that time, it was originally linked to the Indian Planning Commission, which was housed in a large Government building, called Yojana Bhavan. When P.C. Mahalanobis, the distinguished statistician and founder-director of ISI was a member of the Planning Commission, from 1955 to 1967, he wanted this unit to provide research input to the planning process. By the time I joined ISI Mahalanobis had left the Planning Commission, and this unit turned itself into a general research outfit, though later some teaching of post-graduate students started. It continued being housed in that Government building until a new campus for the Delhi branch of ISI was completed. Read more »

I began writing this series eighteen months ago to explore the human experience and human potential in the face of climate change, through the stories we tell. It’s been a remarkable journey for me as I followed trails of questions through new fields of ideas along entirely unexpected paths of enquiry. New vistas revealed themselves, sometimes perilous, always compelling. And so I went. The more I’ve learned, the more I’ve come to realize that our present environmental predicament is actually far worse off—that is to say, more threatening to near-term human wellbeing and civilizational integrity—than most of us recognize. This journey is changing me. So when I now look at contemporary works of fiction about climate change—so-called cli-fi, which I’d hoped might provide fresh insights—so much of it strikes me as somewhat underwhelming before the task: narrow, shallow, tepid, unimaginative, or even dishonest.

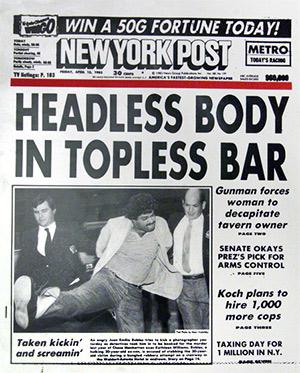

I began writing this series eighteen months ago to explore the human experience and human potential in the face of climate change, through the stories we tell. It’s been a remarkable journey for me as I followed trails of questions through new fields of ideas along entirely unexpected paths of enquiry. New vistas revealed themselves, sometimes perilous, always compelling. And so I went. The more I’ve learned, the more I’ve come to realize that our present environmental predicament is actually far worse off—that is to say, more threatening to near-term human wellbeing and civilizational integrity—than most of us recognize. This journey is changing me. So when I now look at contemporary works of fiction about climate change—so-called cli-fi, which I’d hoped might provide fresh insights—so much of it strikes me as somewhat underwhelming before the task: narrow, shallow, tepid, unimaginative, or even dishonest. When I was growing up during the 1970s, America still had a vibrant and thriving newspaper culture. My hometown New York City boasted a half-dozen dailies to choose from, plus countless neighborhood newspapers. Me and other kids started reading newspapers in about the 5th grade. Sports sections, comics, and movie listings mostly, but still. By middle school, newspapers were all over the place, and not because teachers foisted them upon us, but because kids picked them up on the way to school and read them.

When I was growing up during the 1970s, America still had a vibrant and thriving newspaper culture. My hometown New York City boasted a half-dozen dailies to choose from, plus countless neighborhood newspapers. Me and other kids started reading newspapers in about the 5th grade. Sports sections, comics, and movie listings mostly, but still. By middle school, newspapers were all over the place, and not because teachers foisted them upon us, but because kids picked them up on the way to school and read them.

Although there might be nothing wrong with our hearing, we are quickly losing our ability to practice three formative modalities of democratic listening: Mindful, Aesthetic and Critical. These three modalities support our active participation in sustained, intimate conversations where we learn with and from each other. Millennials in particular struggle to listen to their friends, parents, and teachers for more than a few seconds without their brains becoming distracted by the ubiquitous hand of technology.

Although there might be nothing wrong with our hearing, we are quickly losing our ability to practice three formative modalities of democratic listening: Mindful, Aesthetic and Critical. These three modalities support our active participation in sustained, intimate conversations where we learn with and from each other. Millennials in particular struggle to listen to their friends, parents, and teachers for more than a few seconds without their brains becoming distracted by the ubiquitous hand of technology. Many years ago, I returned to my old high school for a visit with friends who were classmates back in the ’80s. Exploring the school and marveling over what had changed and what remained exactly the same, we ventured into the language lab. The room smelled exactly the same as it had in 1983, and it took me right back to those days of incredibly boring language lessons and sitting in that room with headphones on repeating monotonous phrases.

Many years ago, I returned to my old high school for a visit with friends who were classmates back in the ’80s. Exploring the school and marveling over what had changed and what remained exactly the same, we ventured into the language lab. The room smelled exactly the same as it had in 1983, and it took me right back to those days of incredibly boring language lessons and sitting in that room with headphones on repeating monotonous phrases.

Cogito Ergo Sum? Welcome to the party. There’s a lot more going on out there than we sometimes think: Cephalopods

Cogito Ergo Sum? Welcome to the party. There’s a lot more going on out there than we sometimes think: Cephalopods

A soft-spoken, self-effacing young man from Seoul may be the most listened-to living composer on the planet right now, with two blockbuster works of cinema and TV on his resumé. Not only did Jung Jaeil compose the score for the Oscar-winning Parasite, but his subsequent gig, Squid Game, has just stormed into the record books: Seen and heard by hundreds of millions by now, it has become a global phenomenon, another sign of South Korea’s approaching and encroaching hegemony over all things cultural.

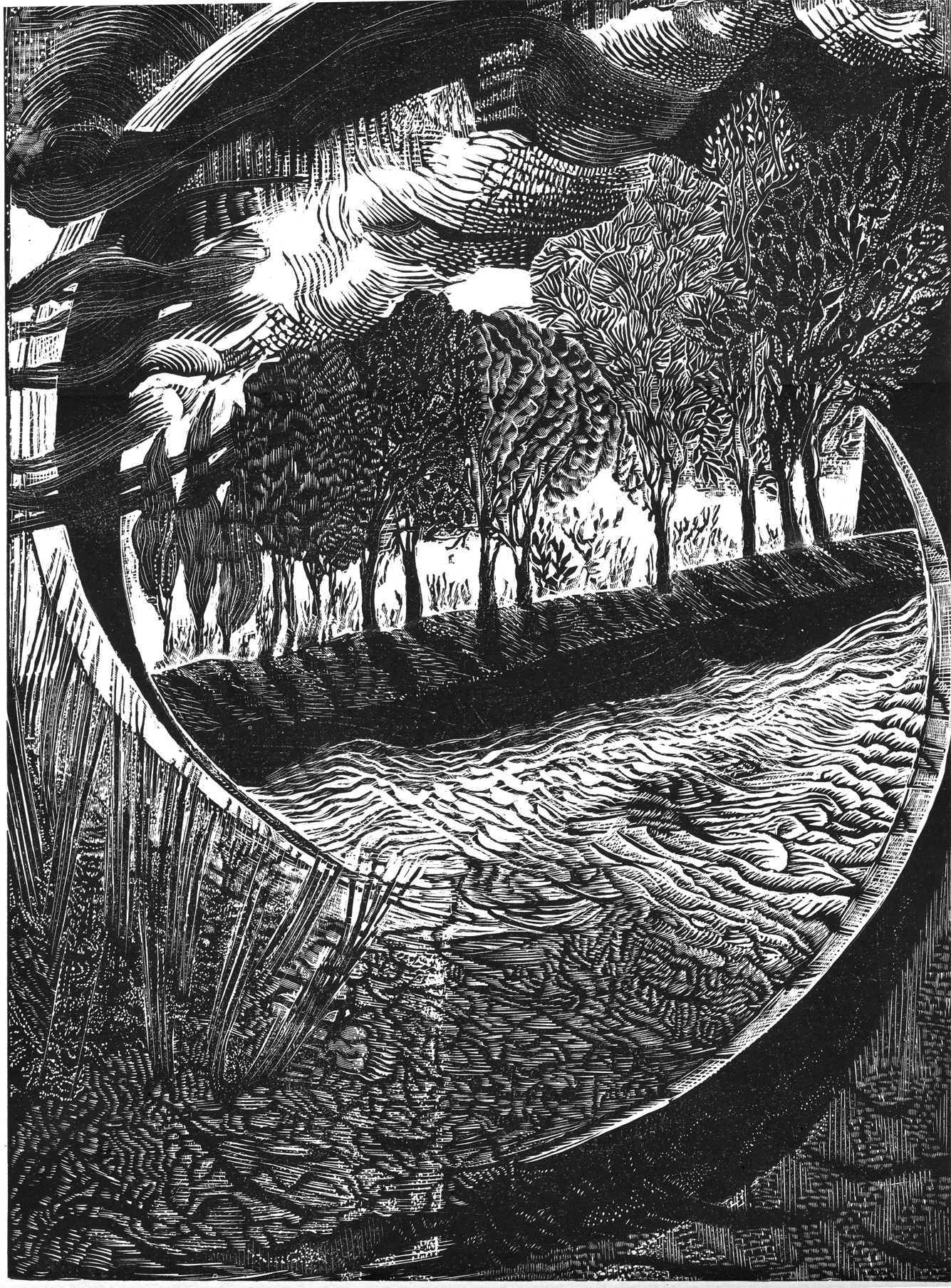

A soft-spoken, self-effacing young man from Seoul may be the most listened-to living composer on the planet right now, with two blockbuster works of cinema and TV on his resumé. Not only did Jung Jaeil compose the score for the Oscar-winning Parasite, but his subsequent gig, Squid Game, has just stormed into the record books: Seen and heard by hundreds of millions by now, it has become a global phenomenon, another sign of South Korea’s approaching and encroaching hegemony over all things cultural. Mary Kuper. “… our curious type of existence here.”

Mary Kuper. “… our curious type of existence here.”