by Eric J. Weiner

Ghazal: India’s Season of Dissent by Karthika Naïr[1]

This year, this night, this hour, rise to salute the season of dissent.

Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims—Indians, all—seek their nation of dissent.

We the people of…they chant: the mantra that birthed a republic.

Even my distant eyes echo flares from this beacon of dissent.

Kolkata, Kasargod, Kanpur, Nagpur, Tripura… watch it spread,

tip to tricoloured tip, then soar: the winged horizon of dissent.

Dibrugarh: five hundred students face the CAA and lathiwielding

cops with Tagore’s song—an age-old tradition of dissent.

Kaagaz nahin dikhayenge… Sab Kuch Yaad Rakha Jayega…

Poetry, once more, stands tall, the Grand Central Station of dissent.

Aamir Aziz, Kausar Munir, Varun Grover, Bisaralli…

Your words, in many tongues, score the sky: first citizens of dissent.

We shall see/ Surely, we too shall see. Faiz-saab, we see your greatness

scanned for “anti-Hindu sentiment”, for the treason of dissent.

Delhi, North-East: death flanks the anthem of a once-secular land

where police now maim Muslims with Sing and die, poison of dissent.

A government of the people, by the people, for the people,

has let slip the dogs of carnage for swift excision of dissent.

Name her, Ka, name her. Umme Habeeba, mere-weeks-old, braves frost and

fascism from Shaheen Bagh: our oldest, finest reason for dissent.

As democracies wither and die throughout the world, Karthika Naïr’s ghazal is a passionate and timely celebration of dissent. The places, peoples, and languages of India dance, crack, bleed, demand, and sing their dissent. Soaring through and beyond the borders of India’s post-colonial history, dissent is the oxygen of freedom, scoring the sky with “words, in many tongues.” The “winged horizon of dissent” delineates “what is” from what should be; it is a practice of the radical imagination, an articulation of audacious hope in the long shadows of broken promises and paralyzing fatalism. As the malcontent’s muse, dissent drives the radical desires of dissident artists and intellectuals, the pedagogues of utopic possibilities at a time in which, as Naïr pointedly says,

…there are no small freedoms…I think that India is unfortunately right now living proof for anybody who wants to see the chronicle of an ascension of totalitarianism. This is the chronology: the loss of greater freedoms comes in the slipstream of the denial of perceived “smaller” freedoms. It’s an incremental approach. First, almost always, they come for the books, the art, the movies, the seemingly frivolous things. I would trace it all the way back to the first book banned in independent India, whatever the reason. Because if you can police the imagination, control the freedom of the mind, then everything else will fall in line. There can never be adequate protection for, or vigilance over, these.

Naïr’s poem is also a warning that without dissenting voices, bodies, and minds the promises—explicit and implied—of democracy, like the bones of a malnourished child, will break. Its demise is barely audible against the pitch of rage spewing from the mouths of autocrats and their sycophants throughout the world. These “dogs of carnage” are unleashed, roaming urban streets and dusty squares, rabidly tearing the flesh of hope from the bones of people who have the audacity to dissent. Read more »

My Presidency College friend Premen was always a voracious reader, particularly of political, social and military history. He often told me of new books in those areas and sometimes persuaded me to read them. But by the time I saw him again in Cambridge, I could see his slow turn from his fascination with Trotsky to Mao. This was in line with a general movement among the young in the European left around that time. Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film La Chinoise captured the restless energy of politically-activist students in contemporary France, foreshadowing the student rebellions in a year or so.

My Presidency College friend Premen was always a voracious reader, particularly of political, social and military history. He often told me of new books in those areas and sometimes persuaded me to read them. But by the time I saw him again in Cambridge, I could see his slow turn from his fascination with Trotsky to Mao. This was in line with a general movement among the young in the European left around that time. Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film La Chinoise captured the restless energy of politically-activist students in contemporary France, foreshadowing the student rebellions in a year or so.

Imagine a world where the prison population was a rough mirror of wider society. In such a world there is a similar spread of rich and poor, highly educated and less educated, as well as a roughly equal proportion of men and women and those from deprived areas and well-off areas. The proportions of different ethnic groups reflect those in the surrounding society, as does the age profile, and having a mental health problem bears no relation to the likelihood of being in prison, neither does being in care in any systematic way increase the chances of ending up as a young offender. In addition, there seems to be no pattern from year to year. Some years there are low levels of crime and in other years the crime rate jumps for no discernible reason. The random nature of the prison population is recognised as providing good evidence for the belief that criminality is simply a result of individuals using their free will to make bad decisions, since we are all equally capable of this. After all, it could be argued, everyone is equal in possessing free will, and crime is a conscious and fully autonomous act in which social and psychological conditions play little part. Anyone, the argument goes, can be selfish or greedy and so succumb to criminality. In such a world, the general view is that prison exists to teach these individuals the error of their ways by providing them with extra motivation to retain their self-control next time temptation beckons.

Imagine a world where the prison population was a rough mirror of wider society. In such a world there is a similar spread of rich and poor, highly educated and less educated, as well as a roughly equal proportion of men and women and those from deprived areas and well-off areas. The proportions of different ethnic groups reflect those in the surrounding society, as does the age profile, and having a mental health problem bears no relation to the likelihood of being in prison, neither does being in care in any systematic way increase the chances of ending up as a young offender. In addition, there seems to be no pattern from year to year. Some years there are low levels of crime and in other years the crime rate jumps for no discernible reason. The random nature of the prison population is recognised as providing good evidence for the belief that criminality is simply a result of individuals using their free will to make bad decisions, since we are all equally capable of this. After all, it could be argued, everyone is equal in possessing free will, and crime is a conscious and fully autonomous act in which social and psychological conditions play little part. Anyone, the argument goes, can be selfish or greedy and so succumb to criminality. In such a world, the general view is that prison exists to teach these individuals the error of their ways by providing them with extra motivation to retain their self-control next time temptation beckons.

I went to France to study abroad as a 20-year-old in my third year of university. At the time, I had been studying French for eight years, but when I arrived in France, I found I was unable to express myself beyond the most rudimentary statements, and I couldn’t understand the rapid-fire questions sprayed at me by curious French students. After attending a dorm party that first weekend, I realized the gap between myself and the French students was simply too large to bridge; the most I could hope for from them was small talk and polite chatter—deep, meaningful conversation, and thus friendship, would be impossible.

I went to France to study abroad as a 20-year-old in my third year of university. At the time, I had been studying French for eight years, but when I arrived in France, I found I was unable to express myself beyond the most rudimentary statements, and I couldn’t understand the rapid-fire questions sprayed at me by curious French students. After attending a dorm party that first weekend, I realized the gap between myself and the French students was simply too large to bridge; the most I could hope for from them was small talk and polite chatter—deep, meaningful conversation, and thus friendship, would be impossible. Upton Sinclair famously remarked that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” It is easy to imagine the sort of scenario that illustrates his point. A drug company rep works to increase how often a certain drug is prescribed, putting aside any worries that it is addictive. A video game designer seeks to increase the number of hours young players spend hooked on a game, not thinking about the impact this might have on their education.

Upton Sinclair famously remarked that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” It is easy to imagine the sort of scenario that illustrates his point. A drug company rep works to increase how often a certain drug is prescribed, putting aside any worries that it is addictive. A video game designer seeks to increase the number of hours young players spend hooked on a game, not thinking about the impact this might have on their education.

“People in the know know him.” That’s what his English translator, Peter Constantine, told me. Grzegorz Kwiatkowski is becoming an important poetic voice from today’s Poland, with six volumes of poetry, and translated editions on the way. His translator added, “He has a strange poetic voice, very original and stark.”

“People in the know know him.” That’s what his English translator, Peter Constantine, told me. Grzegorz Kwiatkowski is becoming an important poetic voice from today’s Poland, with six volumes of poetry, and translated editions on the way. His translator added, “He has a strange poetic voice, very original and stark.”

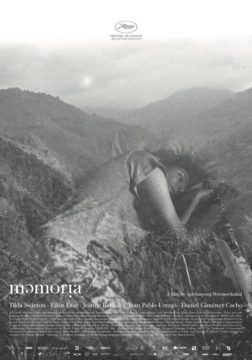

Most cinemas have been open for some time where I live. After having been indoors in restaurants and bars a few times, I was slowly reintroduced to the pleasures of sharing a space with strangers. And finally it felt like the right moment to, once again, set foot in a cinema.

Most cinemas have been open for some time where I live. After having been indoors in restaurants and bars a few times, I was slowly reintroduced to the pleasures of sharing a space with strangers. And finally it felt like the right moment to, once again, set foot in a cinema.

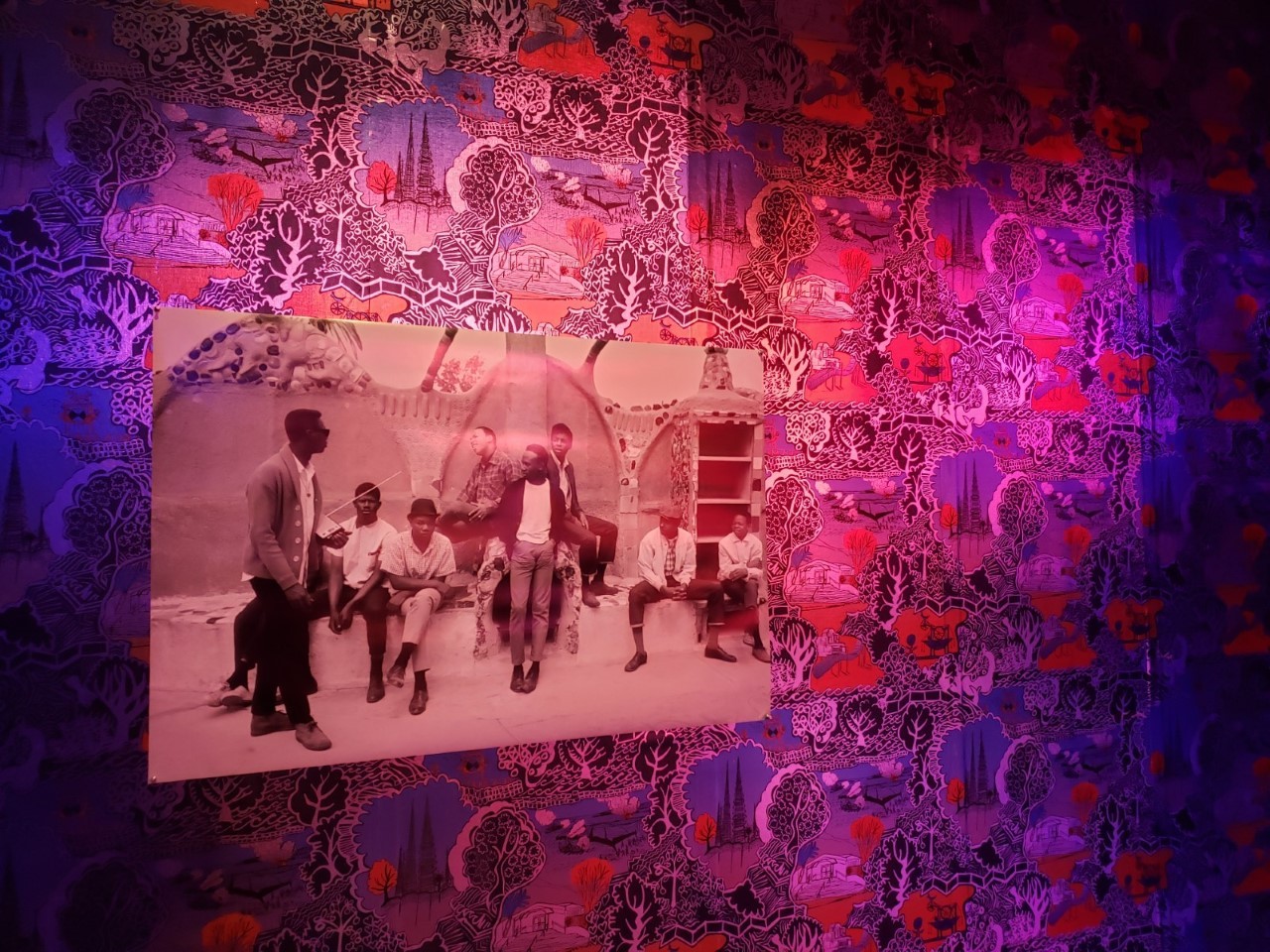

Cauleen Smith. Space Station Chinoiserie #1: Take hold of the Clouds, 2018.

Cauleen Smith. Space Station Chinoiserie #1: Take hold of the Clouds, 2018. Last night I (Danielle Spencer) went to the New York Film Festival screening of Memoria (dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul) in Alice Tully hall at Lincoln Center. I last joined a large gathering 19 months ago, in March of 2020.

Last night I (Danielle Spencer) went to the New York Film Festival screening of Memoria (dir. Apichatpong Weerasethakul) in Alice Tully hall at Lincoln Center. I last joined a large gathering 19 months ago, in March of 2020.