by Usha Alexander

[This is the thirteenth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

In the world of Star Trek, no one ever goes hungry or lacks access to healthcare. No one wants for housing, education, social inclusion or any other basic need. In fact, no citizen of the United Federation of Planets is ever seen to pay for everyday goods or services, only for gambling or special entertainments. The Federation suffers no scarcity of any kind. All waste is presumably fed into the replicators and turned into fresh food or new clothes or whatever is needed. Yet despite ample social safety nets, there’s no end to internecine politicking, human foibles and failures, corruption and vanity, charisma and venality. The world of Star Trek appeals so widely, I think, because it presents us with something colorfully short of a utopia, a flawed human attempt toward a just, caring, and individually enabling social order. It imagines a society based on a shared set of human values—fairness, cooperation, political and economic egalitarianism—where basic human needs are equitably answered so that no one has to compete for basic subsistence and wellbeing. As the venerable Captain Picard has put it, “We’ve overcome hunger and greed, and we’re no longer interested in the accumulation of things.” Some Libertarian Trekkies have been scandalized to realize that Star Trek actually depicts a post-capitalist vision of society.

In the world of Star Trek, no one ever goes hungry or lacks access to healthcare. No one wants for housing, education, social inclusion or any other basic need. In fact, no citizen of the United Federation of Planets is ever seen to pay for everyday goods or services, only for gambling or special entertainments. The Federation suffers no scarcity of any kind. All waste is presumably fed into the replicators and turned into fresh food or new clothes or whatever is needed. Yet despite ample social safety nets, there’s no end to internecine politicking, human foibles and failures, corruption and vanity, charisma and venality. The world of Star Trek appeals so widely, I think, because it presents us with something colorfully short of a utopia, a flawed human attempt toward a just, caring, and individually enabling social order. It imagines a society based on a shared set of human values—fairness, cooperation, political and economic egalitarianism—where basic human needs are equitably answered so that no one has to compete for basic subsistence and wellbeing. As the venerable Captain Picard has put it, “We’ve overcome hunger and greed, and we’re no longer interested in the accumulation of things.” Some Libertarian Trekkies have been scandalized to realize that Star Trek actually depicts a post-capitalist vision of society.

But Star Trek’s world is premised upon the existence of a cheap, concentrated, and non-polluting source of effectively infinite energy. Obviously, no such energy source has ever been discovered (solar-paneled dreamscapes notwithstanding). And the replicator, which eliminates both material waste and scarcity, is a magical technology. The Star Trek vision is also a picture of human chauvinism and hubris, presuming H. Sapiens as the only relevant form of Earthly life. So it falls short of a vivid and plausible imagining of an ecologically sustainable, technologically advanced, and egalitarian human civilization.

It is, of course, too much to expect the creators of Star Trek, by themselves, to fully and flawlessly reimagine our global human society. Indeed, it’s become an aphorism of our age that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. Yet, though this might sound like a joke, at this point the matter is all too serious, and reimagining human civilization is a project we all must engage with, to whatever extent we’re able. Read more »

What is the present? When did it begin? Stoics simply consult the calendar for an answer, where they find each new span of 24 hours reassuringly dubbed Today. Archaeologists speak of “Years Before Present” when referring to the time prior to January 1, 1950, the arbitrarily chosen inauguration of the era of radiocarbon dating following the explosion of the first atomic bombs. And the Judeo-Christian West makes of the present age a spatio-temporal chronotope, a narrative rooted in the time and place of birth of a particular figure, whose “presence” as guarantor is inextricable from the dating system, whether the appellations used are the frankly messianic Before Christ and Anno Domini, or the compromise variations on an ecumenical “Common Era”.

What is the present? When did it begin? Stoics simply consult the calendar for an answer, where they find each new span of 24 hours reassuringly dubbed Today. Archaeologists speak of “Years Before Present” when referring to the time prior to January 1, 1950, the arbitrarily chosen inauguration of the era of radiocarbon dating following the explosion of the first atomic bombs. And the Judeo-Christian West makes of the present age a spatio-temporal chronotope, a narrative rooted in the time and place of birth of a particular figure, whose “presence” as guarantor is inextricable from the dating system, whether the appellations used are the frankly messianic Before Christ and Anno Domini, or the compromise variations on an ecumenical “Common Era”.

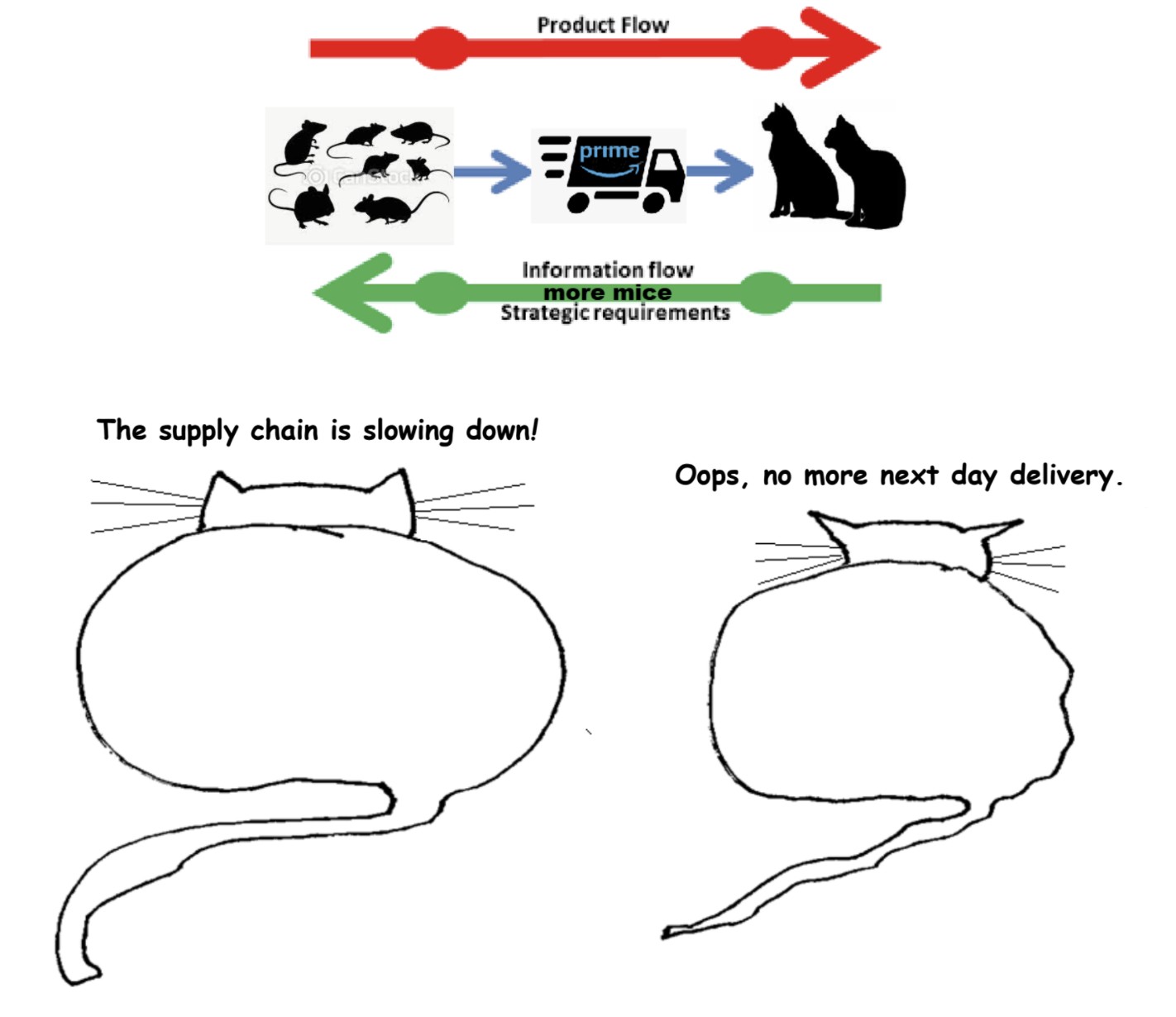

I recently spent a few weeks in the UK, which is suffering from a labor shortage post lockdown like the US. Though, unlike the US, some of the UK’s problems are self-inflicted Brexit wounds. The shortages are rippling through every sector, and as in the US, that includes hospitality. Coming out of lockdown, no doubt initiated by hygiene concerns, some restaurants I visited in New York used QR codes instead of handing out menus.

I recently spent a few weeks in the UK, which is suffering from a labor shortage post lockdown like the US. Though, unlike the US, some of the UK’s problems are self-inflicted Brexit wounds. The shortages are rippling through every sector, and as in the US, that includes hospitality. Coming out of lockdown, no doubt initiated by hygiene concerns, some restaurants I visited in New York used QR codes instead of handing out menus.  Shortly after my arrival at Cambridge I struck up a warm friendship with a very bright young faculty member, Jim Mirrlees (who was to get the Nobel Prize later), recently returned from a stint of research in India. (Although he was a high-powered theoretical economist, he had what seemed to me an almost religious/moral fervor for doing something to help poor countries). Even more than Frank Hahn, he got involved in the theoretical analysis in my dissertation, and helped me in making some of the proofs of my propositions simpler and less inelegant.

Shortly after my arrival at Cambridge I struck up a warm friendship with a very bright young faculty member, Jim Mirrlees (who was to get the Nobel Prize later), recently returned from a stint of research in India. (Although he was a high-powered theoretical economist, he had what seemed to me an almost religious/moral fervor for doing something to help poor countries). Even more than Frank Hahn, he got involved in the theoretical analysis in my dissertation, and helped me in making some of the proofs of my propositions simpler and less inelegant. Considered the epitome of genius, Albert Einstein appears like a wellspring of intellect gushing forth fully formed from the ground, without precedents or process. There was little in his lineage to suggest genius; his parents Hermann and Pauline, while having a pronounced aptitude for mathematics and music, gave no inkling of the off-scale progeny they would bring forth. His career itself is now the stuff of legend. In 1905, while working on physics almost as a side-project while sustaining a day job as technical patent clerk, third class, at the patent office in Bern, he published five papers that revolutionized physics and can only be compared to Isaac Newton’s burst of high creativity as he sought refuge from the plague. Among these were papers heralding his famous equation, E=mc^2, along with ones describing special relativity, Brownian motion and the basis of the photoelectric effect that cemented the particle nature of light. In one of history’s ironic episodes, it was the photoelectric effect paper rather than the one on special relativity that Einstein himself called revolutionary and that won him the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics.

Considered the epitome of genius, Albert Einstein appears like a wellspring of intellect gushing forth fully formed from the ground, without precedents or process. There was little in his lineage to suggest genius; his parents Hermann and Pauline, while having a pronounced aptitude for mathematics and music, gave no inkling of the off-scale progeny they would bring forth. His career itself is now the stuff of legend. In 1905, while working on physics almost as a side-project while sustaining a day job as technical patent clerk, third class, at the patent office in Bern, he published five papers that revolutionized physics and can only be compared to Isaac Newton’s burst of high creativity as he sought refuge from the plague. Among these were papers heralding his famous equation, E=mc^2, along with ones describing special relativity, Brownian motion and the basis of the photoelectric effect that cemented the particle nature of light. In one of history’s ironic episodes, it was the photoelectric effect paper rather than the one on special relativity that Einstein himself called revolutionary and that won him the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics.

For my whole life, the world has been ending. For various alleged reasons. . . but always there’s been an overhang of dread and fear, the end times already here, human cussedness and sinfulness and greed at work in every moment, everywhere, eating away at what’s left of goodness and preparing the Day of Wrath, the horror, the tribulation, the Last Conflict, the End.

For my whole life, the world has been ending. For various alleged reasons. . . but always there’s been an overhang of dread and fear, the end times already here, human cussedness and sinfulness and greed at work in every moment, everywhere, eating away at what’s left of goodness and preparing the Day of Wrath, the horror, the tribulation, the Last Conflict, the End.

Baseera Khan. A New Territory, 2021.

Baseera Khan. A New Territory, 2021. If we take action now to mitigate global climate change, it might make life a little worse for people now and in the near future, but it will make life much better for people further in the future. Suppose, for whatever reason, we do nothing.

If we take action now to mitigate global climate change, it might make life a little worse for people now and in the near future, but it will make life much better for people further in the future. Suppose, for whatever reason, we do nothing.

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.