by Hari Balasubramanian

The slim, green book Natural History of Western Massachusetts is one of my favorites. Compressed into its hundred odd pages are articles and visuals that describe the essential natural features of the Amherst region, where I’ve lived since 2008. I turn to it every time something outdoors piques my interest — a new tree, bird or mammal, a geological feature.

The slim, green book Natural History of Western Massachusetts is one of my favorites. Compressed into its hundred odd pages are articles and visuals that describe the essential natural features of the Amherst region, where I’ve lived since 2008. I turn to it every time something outdoors piques my interest — a new tree, bird or mammal, a geological feature.

One section that I particularly enjoy is the ‘Nature Calendar’ at the end. The calendar gives predictions on what to expect in each phase of a month; there’s approximately one prediction for every 3-day period. In early November, for example, it says “dandelions may still be blooming in protected areas”, and indeed some wildflowers do retain their bright colors despite freezing fall temperatures. It also says for the same month that “flocks of cedar-waxwings may be migrating through the region”. This was such a specific claim, but it is accurate: I was startled to see a flock of nearly a hundred waxwings swirling around bare trees on a rocky mountaintop this November.

The scientific analysis of such seasonal patterns is called phenology. Wikipedia defines it as “the study of periodic events in biological life cycles and how these are influenced by seasonal and interannual variations, as well as habitat factors (such as elevation)”. It’s a clunky, textbook kind of definition but the gist is clear enough. I find myself drawn to phenology for many reasons. Read more »

Everything in the universe that’s visible from your location on Earth passes by overhead every day. We’re usually able see only the stars, galaxies, planets, and so on that are in the sky when the sun is not; we become aware of them when the sun sets and Earth’s shadow rises from the eastern horizon. But all of them are there at some point in the day. We picnic beneath the winter constellation Orion in summer and walk beneath the Summer Triangle on the short days of winter. The moon also crosses the sky every day, sometimes in the daytime, and sometimes too close to the sun to be seen.

Everything in the universe that’s visible from your location on Earth passes by overhead every day. We’re usually able see only the stars, galaxies, planets, and so on that are in the sky when the sun is not; we become aware of them when the sun sets and Earth’s shadow rises from the eastern horizon. But all of them are there at some point in the day. We picnic beneath the winter constellation Orion in summer and walk beneath the Summer Triangle on the short days of winter. The moon also crosses the sky every day, sometimes in the daytime, and sometimes too close to the sun to be seen. I had my first panic attack at age sixteen, which was (deargod) over 35 years ago. It happened during school, much to my teenage mortification. Some friends and I were hanging out in our high school newspaper office during a free period, sprawled on one of the crapped-out couches under the blinking fluorescent lights, just shooting the shit. All of a sudden, a wave of horror swept over me—no, that’s not the right word. It was a feeling of fear mixed with a kind of existential dread, washing over me in waves, and then my heart was pounding, the walls were closing in, and I was gripped with an intense feeling of unreality. (This is something that people with panic disorder don’t often explain—or maybe it’s different for everyone. But for me the worst part of a panic attack is the

I had my first panic attack at age sixteen, which was (deargod) over 35 years ago. It happened during school, much to my teenage mortification. Some friends and I were hanging out in our high school newspaper office during a free period, sprawled on one of the crapped-out couches under the blinking fluorescent lights, just shooting the shit. All of a sudden, a wave of horror swept over me—no, that’s not the right word. It was a feeling of fear mixed with a kind of existential dread, washing over me in waves, and then my heart was pounding, the walls were closing in, and I was gripped with an intense feeling of unreality. (This is something that people with panic disorder don’t often explain—or maybe it’s different for everyone. But for me the worst part of a panic attack is the  Sughra Raza. Another Morning. Venice, July 2012.

Sughra Raza. Another Morning. Venice, July 2012. We primates of the

We primates of the

At ISI one day the American economist Daniel Thorner walked into my office and engaged me in a lively conversation, with his dancing eyebrows and unbounded enthusiasm. I had, of course, read his many substantive papers in EW on Indian agriculture and economic history. I also knew how in the early 1950’s, in the McCarthy era, he had lost his job at University of Pennsylvania for refusing to give information on his leftist friends, and then went on to live in India, with his wife Alice (a fellow India-scholar) for 10 years, before taking up a position in Paris. Now when he came to see me he had just read my EPW paper showing on the basis of NSS data that poverty had increased over the 1960’s in rural India. He asked me not to put so much trust on NSS data (he jokingly said that increasing poverty estimates by NSS data might be a reflection more of the increasing sense of misery on the part of the underpaid NSS workers), and to accompany him in his next trip to Punjab villages where he promised to introduce me to beer-drinking tractor-driving women farmers, the harbingers of the future of agricultural capitalism in India. Much of what he said was, of course, tongue-in-cheek, and we became good friends. But this friendship was to be a ‘brief candle’, as cancer soon cut his life short.

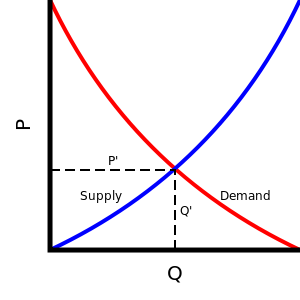

At ISI one day the American economist Daniel Thorner walked into my office and engaged me in a lively conversation, with his dancing eyebrows and unbounded enthusiasm. I had, of course, read his many substantive papers in EW on Indian agriculture and economic history. I also knew how in the early 1950’s, in the McCarthy era, he had lost his job at University of Pennsylvania for refusing to give information on his leftist friends, and then went on to live in India, with his wife Alice (a fellow India-scholar) for 10 years, before taking up a position in Paris. Now when he came to see me he had just read my EPW paper showing on the basis of NSS data that poverty had increased over the 1960’s in rural India. He asked me not to put so much trust on NSS data (he jokingly said that increasing poverty estimates by NSS data might be a reflection more of the increasing sense of misery on the part of the underpaid NSS workers), and to accompany him in his next trip to Punjab villages where he promised to introduce me to beer-drinking tractor-driving women farmers, the harbingers of the future of agricultural capitalism in India. Much of what he said was, of course, tongue-in-cheek, and we became good friends. But this friendship was to be a ‘brief candle’, as cancer soon cut his life short. Every Econ 101 student learns the basic model of demand and supply. It’s pretty straight forward. Picture a graph with the price of a product or service on the vertical axis and the quantity supplied and demanded on the horizontal axis. There are two curves drawn on this graph: the demand curve and the supply curve. The demand curve is downward sloping because as prices decrease, consumers are willing to buy more. The supply curve is upward sloping because producers are willing to supply more when they are paid more. The “competitive equilibrium price” of the product or service is where supply equals demand: two curves intersect. When prices are higher than the equilibrium price, supply is greater than demand: there is “excess supply”. This makes sense: at higher prices, suppliers are going to be happy to sell more, but consumers aren’t willing to buy as much.

Every Econ 101 student learns the basic model of demand and supply. It’s pretty straight forward. Picture a graph with the price of a product or service on the vertical axis and the quantity supplied and demanded on the horizontal axis. There are two curves drawn on this graph: the demand curve and the supply curve. The demand curve is downward sloping because as prices decrease, consumers are willing to buy more. The supply curve is upward sloping because producers are willing to supply more when they are paid more. The “competitive equilibrium price” of the product or service is where supply equals demand: two curves intersect. When prices are higher than the equilibrium price, supply is greater than demand: there is “excess supply”. This makes sense: at higher prices, suppliers are going to be happy to sell more, but consumers aren’t willing to buy as much.

Sughra Raza. First Snow 2022.

Sughra Raza. First Snow 2022. On the anniversary of the attempt by Donald Trump and some of his supporters to subvert the 2020 US presidential election, Joe Biden denounced those who “place a dagger at the throat of democracy.” To which one can only say: About bloody time! The threat posed by Trump and the Republican party to America’s democratic institutions–highly imperfect though they are–is so obvious that anyone who has a bully pulpit should be pounding out a warning at every opportunity.

On the anniversary of the attempt by Donald Trump and some of his supporters to subvert the 2020 US presidential election, Joe Biden denounced those who “place a dagger at the throat of democracy.” To which one can only say: About bloody time! The threat posed by Trump and the Republican party to America’s democratic institutions–highly imperfect though they are–is so obvious that anyone who has a bully pulpit should be pounding out a warning at every opportunity.