by Rebecca Baumgartner

Apsley Cherry-Garrard, the Antarctic explorer who would become famous for documenting Robert Falcon Scott’s expedition in his book The Worst Journey in the World, wrote a letter in 1919 in which he cast doubt on the purity of the motives of one of the expedition members, Lieutenant Edward “Teddy” Evans: “There will…be an unprinted reference to the Antarctic as a white wall upon which some people have a passion for writing their names. If the cap fits let him put it on.”

Photograph by: Elaine Hood/National Science Foundation (NSF) License: Public Domain

One of the fascinating things about Antarctica is how its extreme conditions put the best and worst of humanity into stark relief. From the very beginning, the motives of the people going there have been multi-layered, an adulterated mix of ego, commercial incentive, scientific curiosity, wanderlust, and the siren call of the unknown. Even Cherry-Garrard himself, not having any training or scientific skill to speak of but coming from money, ended up buying his way onto Scott’s team. Geographic landmarks were routinely named after sponsors and backers of various expeditions. The very earliest journeys were motivated entirely by a money-making desire to kill as many seals and whales as possible. One member of Scott’s team was photographed happily eating a tin of Heinz Baked Beans as part of a sponsorship deal. There has never been a time when commercialization wasn’t a major part of the Antarctic enterprise. And it’s likely to stay that way, simply due to the sheer difficulty and expense of getting there in the first place and equipping yourself to survive once there. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in The November Sun, 2020.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in The November Sun, 2020.

Going back and reading one’s favorite authors is like seeing an old friend after a long absence: things fall into place, you remember why it is you get along with and like the other person, and their idiosyncrasies and unique character reappear and interact with your own, making old patterns reemerge and lighting up parts of you that have long been dormant.

Going back and reading one’s favorite authors is like seeing an old friend after a long absence: things fall into place, you remember why it is you get along with and like the other person, and their idiosyncrasies and unique character reappear and interact with your own, making old patterns reemerge and lighting up parts of you that have long been dormant. The western admirers of Amartya Sen as a public intellectual may not be aware that he is actually in a long line of globally engaged cultural elite that Bengal has produced. (This is true to some extent of the elite elsewhere in India as well, particularly around Chennai and Mumbai, but I think in sheer scale over the last two hundred years, Bengal may have a special claim). One aspect of this phenomenon is worth reflecting on. These members of the cultural elite were well-versed in the manifold offerings of the West, but they came to them with a solid grounding in the cultural wealth of India. Take Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833). He was, as Nehru describes him in his Discovery of India, “deeply versed in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, ..a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture, …the world’s first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion.” He contributed to the development of Bengali prose. He was a social reformer in Hindu society, actively engaged in serious religious debates with Christian missionaries in India, and a champion of women’s rights and freedom of press (standing up against colonial censorship). Yet when he went to England he caused some stir as the urbane face of a reforming Indian society, was active in campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act as a step to British democracy. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham reportedly even began a campaign to elect him to the British Parliament (but Roy caught meningitis and died in Bristol soon after).

The western admirers of Amartya Sen as a public intellectual may not be aware that he is actually in a long line of globally engaged cultural elite that Bengal has produced. (This is true to some extent of the elite elsewhere in India as well, particularly around Chennai and Mumbai, but I think in sheer scale over the last two hundred years, Bengal may have a special claim). One aspect of this phenomenon is worth reflecting on. These members of the cultural elite were well-versed in the manifold offerings of the West, but they came to them with a solid grounding in the cultural wealth of India. Take Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833). He was, as Nehru describes him in his Discovery of India, “deeply versed in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, ..a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture, …the world’s first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion.” He contributed to the development of Bengali prose. He was a social reformer in Hindu society, actively engaged in serious religious debates with Christian missionaries in India, and a champion of women’s rights and freedom of press (standing up against colonial censorship). Yet when he went to England he caused some stir as the urbane face of a reforming Indian society, was active in campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act as a step to British democracy. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham reportedly even began a campaign to elect him to the British Parliament (but Roy caught meningitis and died in Bristol soon after).

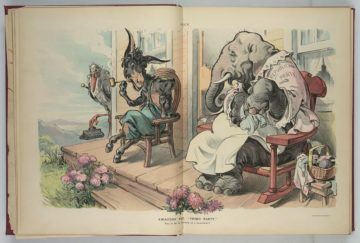

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve.

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve. My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom.

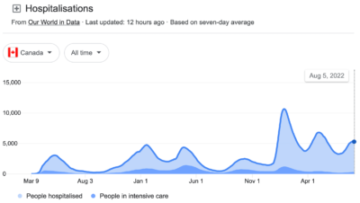

My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom. A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.