by Mike Bendzela

Over thirty years ago, my then-partner-now-spouse, Don, began planting heritage apple trees on the small farm where we are tenants, in an attempt to partially restore the historical orchard of Herbert W. Dow, traditional Maine farmer and cider-imbiber.

Herbert’s original, handwritten map of the apple trees he grew out back was still in a desk in the house when Don moved here in the 1970s; so, we have been able to research and replant some of the old varieties Herbert grew. We decided we would tend the trees “organically,” or something equivalent, because, you know, toxic chemicals and all that, and we would sell rare apples to local markets.

This organic ideal did not last long, however. Little did we know what nature had in store for us.

Swiss botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle, whose view profoundly influenced Charles Darwin, declared that “all nature is at war, one organism with another.”

The greater choke the smaller, the longest livers replace those which last for a shorter period, the more prolific gradually make themselves masters of the ground.

The belief that having “dominion” over nature exempts the husbandman from this Darwinian fray is romanticized claptrap. Raising any crop requires a farmer to tend simultaneously to the needs of a hospital and slaughterhouse. What follows is a compendium of just a few of the horrors baked into your apple pie. Read more »

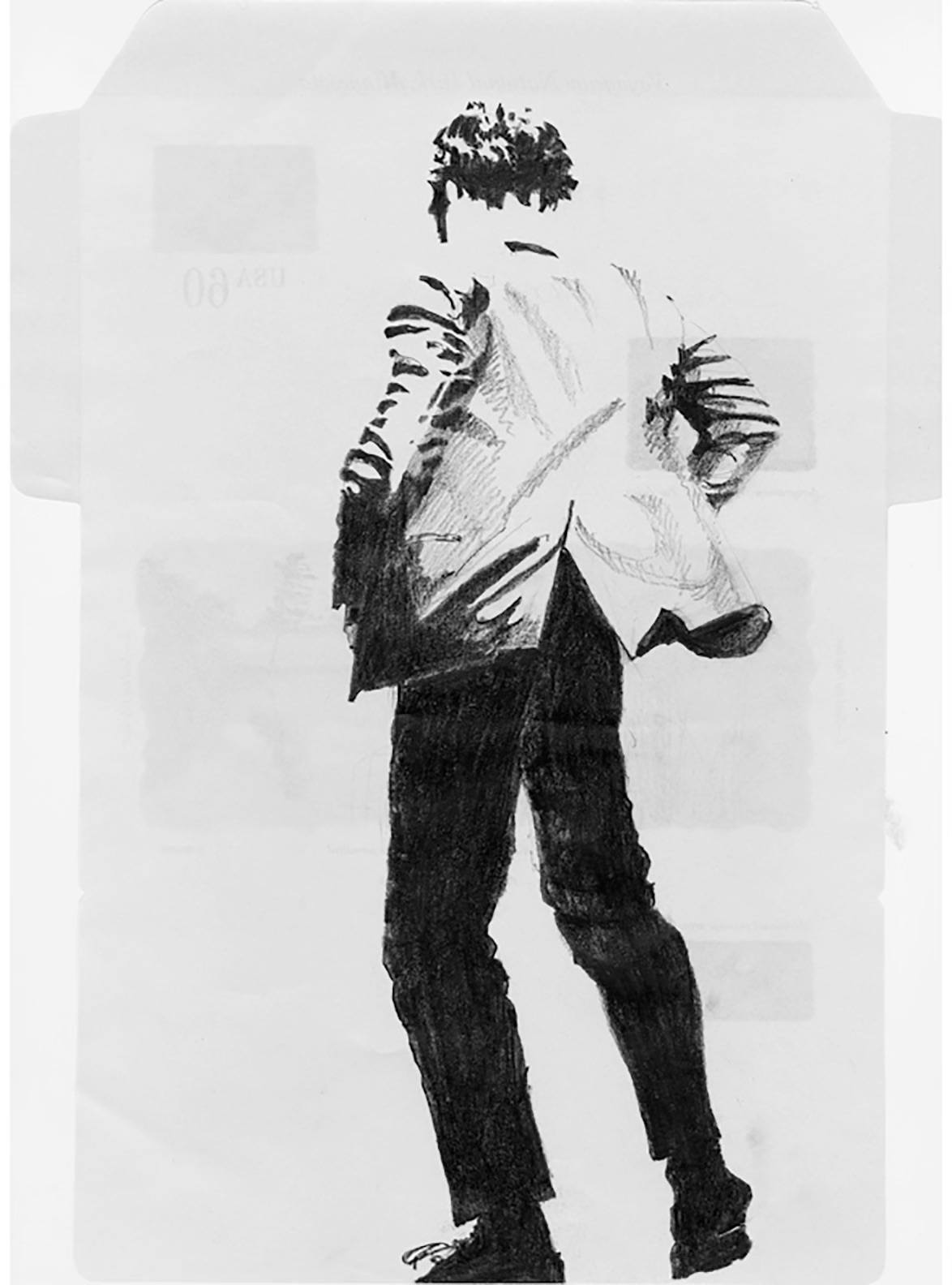

Sughra Raza. Untitled, ca 2008.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, ca 2008.

This past spring, I found myself sitting, masked, at a wooden desk among a scattering of scientific researchers at the Museo Galileo in Florence. Next to me was a thick reference book on the history of astronomical instruments and a smaller work on the sundials and other measuring devices built into the churches of Florence to mark the cyclical turning points of cosmic time. The gnomon of Santa Maria del Fiore, for instance, consisted of a bronzina, a small hole set into the lantern ninety meters above that acted as a camera oscura and projected an image of the sun onto the cathedral floor far below. At noon on the day of the solstice, the solar disc superimposed itself perfectly onto a round marble slab, not quite a yard in diameter, situated along the inlaid meridian. I studied the explanations of astronomical quadrants and astrolabes and the armilla equinoziale, the armillary sphere of Santa Maria Novella, made up of two conjoined iron rings mounted on the façade that told the time of day and year based on the position of their elliptical shadow, when all at once it occurred to me that I’d wanted to write about something else altogether, about a person I occasionally encountered, a phantom living somewhere inside me: the young woman who’d decided not to leave, not to move to Berlin after all, to rip up the letter of acceptance to the art academy she received all those years ago and to stay put, in New York. Alive somewhere, in some other iteration of being, was a parallel existence in an alternative universe, one of the infinite spheres of possibility in which I’d decided differently and become a different woman.

This past spring, I found myself sitting, masked, at a wooden desk among a scattering of scientific researchers at the Museo Galileo in Florence. Next to me was a thick reference book on the history of astronomical instruments and a smaller work on the sundials and other measuring devices built into the churches of Florence to mark the cyclical turning points of cosmic time. The gnomon of Santa Maria del Fiore, for instance, consisted of a bronzina, a small hole set into the lantern ninety meters above that acted as a camera oscura and projected an image of the sun onto the cathedral floor far below. At noon on the day of the solstice, the solar disc superimposed itself perfectly onto a round marble slab, not quite a yard in diameter, situated along the inlaid meridian. I studied the explanations of astronomical quadrants and astrolabes and the armilla equinoziale, the armillary sphere of Santa Maria Novella, made up of two conjoined iron rings mounted on the façade that told the time of day and year based on the position of their elliptical shadow, when all at once it occurred to me that I’d wanted to write about something else altogether, about a person I occasionally encountered, a phantom living somewhere inside me: the young woman who’d decided not to leave, not to move to Berlin after all, to rip up the letter of acceptance to the art academy she received all those years ago and to stay put, in New York. Alive somewhere, in some other iteration of being, was a parallel existence in an alternative universe, one of the infinite spheres of possibility in which I’d decided differently and become a different woman. Among other things London School of Economics is associated in my mind with bringing me in touch with one of the most remarkable persons I have ever met in my life, and someone who has been a dear friend over nearly four decades since then. This is Jean Drèze.

Among other things London School of Economics is associated in my mind with bringing me in touch with one of the most remarkable persons I have ever met in my life, and someone who has been a dear friend over nearly four decades since then. This is Jean Drèze. Although by no means the only ones, two models of human beings and their relation to society are prominent in modern social and political thought. At first glance they seem incompatible, but I want to sketch them out and start to establish how they might plausibly be made to fit together.

Although by no means the only ones, two models of human beings and their relation to society are prominent in modern social and political thought. At first glance they seem incompatible, but I want to sketch them out and start to establish how they might plausibly be made to fit together.

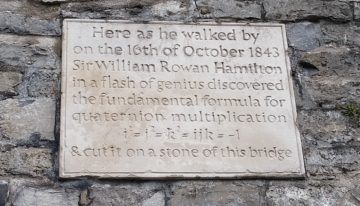

Anneliese Hager. Untitled. ca. 1940-1950

Anneliese Hager. Untitled. ca. 1940-1950