by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

As with game theory, I also attended some courses in Berkeley in another relatively new subject for me, Psychology and Economics (later called Behavioral Economics). In particular I liked the course jointly taught by George Akerlof and Daniel Kahneman (then at Berkeley Psychology Department, later at Princeton). I remember during that time I was once talking to George when my friend and colleague the econometrician Tom Rothenberg came over and asked me to describe in one sentence what I had learned so far from the Akerlof-Kahneman course. I said, somewhat flippantly: “Kahneman is telling us that people are dumber than we economists think, and George is telling us that people are nicer than we economists think”. George liked this description so much that in the next class he started the lecture with my remark. On the dumbness of people I later read somewhere that Kahneman’s earlier fellow-Israeli co-author Amos Tversky once said when asked what he was working on, “My colleagues, they study artificial intelligence; me, I study natural stupidity.”

As with game theory, I also attended some courses in Berkeley in another relatively new subject for me, Psychology and Economics (later called Behavioral Economics). In particular I liked the course jointly taught by George Akerlof and Daniel Kahneman (then at Berkeley Psychology Department, later at Princeton). I remember during that time I was once talking to George when my friend and colleague the econometrician Tom Rothenberg came over and asked me to describe in one sentence what I had learned so far from the Akerlof-Kahneman course. I said, somewhat flippantly: “Kahneman is telling us that people are dumber than we economists think, and George is telling us that people are nicer than we economists think”. George liked this description so much that in the next class he started the lecture with my remark. On the dumbness of people I later read somewhere that Kahneman’s earlier fellow-Israeli co-author Amos Tversky once said when asked what he was working on, “My colleagues, they study artificial intelligence; me, I study natural stupidity.”

Of course, by dumbness or stupidity in this context economists really mean departures from rationality, and knowing that people are often irrational, behavioral economics is really about the systematic departures from rationality which gives the subject its analytical coherence, that there is method in the madness as Polonius says in Hamlet. And in the departures from self-centered individual rationality social norms and fellow-feeling (like empathy and sympathy and social solidarity) often play an important role. In Berkeley I had a friendly colleague for many years, Matthew Rabin (now at Harvard), from whose talks and writings I have learnt a great deal on fairness in social preferences in a modified game-theory framework, apart from common human errors in probabilistic reasoning and human frailties like individual self-control problems. These are big changes in traditional ways of thinking in Economics. Read more »

![Righting America at the Creation Museum (Medicine, Science, and Religion in Historical Context) by [Susan L. Trollinger, William Vance Trollinger]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/511yK1hsSBL.jpg)

Herschel Walker claims that we have enough trees already, that we send China our clean air and they return their dirty air to us, that evolution makes no sense since there are still apes around, and freely offers other astute scientific insights. He may be among the least knowledgeable (to put it mildly) candidates running for office, but he’s not alone and many candidates, I suspect, are also surprisingly innocent of basic math and science. Since innumeracy and science illiteracy remain significant drivers of bad policy decisions, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that congressional candidates (house and senate) be obliged to get a passing grade on a simple quiz.

Herschel Walker claims that we have enough trees already, that we send China our clean air and they return their dirty air to us, that evolution makes no sense since there are still apes around, and freely offers other astute scientific insights. He may be among the least knowledgeable (to put it mildly) candidates running for office, but he’s not alone and many candidates, I suspect, are also surprisingly innocent of basic math and science. Since innumeracy and science illiteracy remain significant drivers of bad policy decisions, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that congressional candidates (house and senate) be obliged to get a passing grade on a simple quiz. Philip Guston. Still Life, 1962.

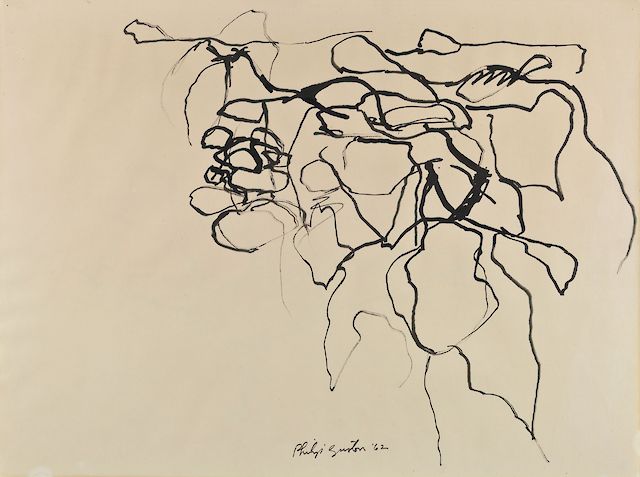

Philip Guston. Still Life, 1962.

I recently listened to a discussion on the topic of

I recently listened to a discussion on the topic of  This summer I noticed that I was sharing a lot of sunset photos on social media. I don’t think of myself as a photographer, and I’m much more likely to share words than images. When I thought about it, I realized this wasn’t a sudden change. I’ve been taking the odd set of sunset pictures with my Canon every now and then, and I’ve noticed that my eyes are increasingly drawn to the sky and the light when I look at landscape photos.

This summer I noticed that I was sharing a lot of sunset photos on social media. I don’t think of myself as a photographer, and I’m much more likely to share words than images. When I thought about it, I realized this wasn’t a sudden change. I’ve been taking the odd set of sunset pictures with my Canon every now and then, and I’ve noticed that my eyes are increasingly drawn to the sky and the light when I look at landscape photos.