by David S. Greer

John Keats can be forgiven for overlooking the spiders in his ode “To Autumn”. Who can blame him for accentuating the positive, given the health issues that eventually overcame him, barely 25, in his rude room by the foot of the Spanish Steps?

My sometime island abode in the Salish Sea, the inland sea that touches Vancouver and Seattle and is home to the Canadian Gulf Islands and the American San Juans, is a long way from the Spanish Steps and a favorite haunt of spiders in autumn. Early on a late September morning on the cliff-edge path to Gowlland Point, dewdrops sparkle like diamonds in elaborate silken webs draped over long grasses with exquisite care. Spiders are to autumn as strawberries are to June. What’s not to like?

An older cabin in the woods is an invitation to wildlife invasion. Black-tailed deer content themselves with napping under the deck, and river otters make the quarter-mile trek from the ocean on rare occasions to investigate the crawl space as a potential den, but entering the interior of the cabin is the particular province of birds and bats (accidentally) and spiders (less so). Field mice would gladly join the parade, and have done so in the past, but for the time being are flummoxed by plugs of steel wool in every mouse-sized hole. Their tactical engineering squads are believed to be working on solutions every day. As for other invaders, live rescues are my preferred approach. Hummingbirds and wrens can be trapped in Tupperware containers, a sheet of cardboard slipped over the opening, and released outdoors. A juice glass will suffice for errant wasps and moths. Read more »

The international academic conference circuit—for an amusing account of such circuits, one may read the British writer David Lodge’s novel Small World, which is second in his trilogy of campus novels, the first of which Changing Places is largely on Berkeley in the 1960’s—also brought me to some potentially hazardous situations. Once a reception given for us conference participants by the King of Spain indirectly helped me in what could have been a serious loss from a pickpocket in Madrid. The public reception hall was not far from the hotel where we were staying. I was walking there from the hotel with a fellow conference participant. I was busy explaining a particular point to her in conversation when I had a half-sense that two young women who brushed by seemed a bit too close, and I ignored that for a minute. The next minute I felt the inside of my jacket pocket and it was gone—a wallet containing not just money but a few important cards including credit cards (since then I have been careful not to put everything in the same wallet or pocket). So I excused myself from my companion and ran to a nearby policeman and told him about it. He brought out a whistle and made a signaling sound. Within 5 minutes another policeman from the opposite pavement came toward me with my wallet and asked me to check if everything was in place. Those two unlucky young women did not realize that as the King was to be there soon, the whole area was thick with plain-clothes policemen.

The international academic conference circuit—for an amusing account of such circuits, one may read the British writer David Lodge’s novel Small World, which is second in his trilogy of campus novels, the first of which Changing Places is largely on Berkeley in the 1960’s—also brought me to some potentially hazardous situations. Once a reception given for us conference participants by the King of Spain indirectly helped me in what could have been a serious loss from a pickpocket in Madrid. The public reception hall was not far from the hotel where we were staying. I was walking there from the hotel with a fellow conference participant. I was busy explaining a particular point to her in conversation when I had a half-sense that two young women who brushed by seemed a bit too close, and I ignored that for a minute. The next minute I felt the inside of my jacket pocket and it was gone—a wallet containing not just money but a few important cards including credit cards (since then I have been careful not to put everything in the same wallet or pocket). So I excused myself from my companion and ran to a nearby policeman and told him about it. He brought out a whistle and made a signaling sound. Within 5 minutes another policeman from the opposite pavement came toward me with my wallet and asked me to check if everything was in place. Those two unlucky young women did not realize that as the King was to be there soon, the whole area was thick with plain-clothes policemen.

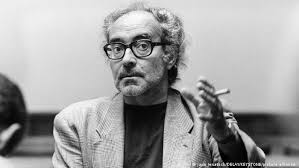

On the 13th September 2022, Jean-Luc Godard, the Franco-Swiss film-director, film-poet, film-philosopher, died at the age of 91. One of the most imaginative, rebellious, truly courageous artists on this planet whose existence, in more ways than can be enumerated in language, changed the face of our modernity, decided to end his life through assisted suicide, which is a legal practice in Switzerland, the country he had been living in since 1976, and in which he had spent his youth. He was not ill, ‘but exhausted’. In addition to everything else, his last action resonates with a magnitude that is as powerful as a political stand as it is as a last demonstration of a personal ethics which can be summarised as: moral integrity or nothing. A moral integrity, which he brought to bear indefatigably over the course of a lifetime in pursuit of freedom, resolution and independence – at whatever price.

On the 13th September 2022, Jean-Luc Godard, the Franco-Swiss film-director, film-poet, film-philosopher, died at the age of 91. One of the most imaginative, rebellious, truly courageous artists on this planet whose existence, in more ways than can be enumerated in language, changed the face of our modernity, decided to end his life through assisted suicide, which is a legal practice in Switzerland, the country he had been living in since 1976, and in which he had spent his youth. He was not ill, ‘but exhausted’. In addition to everything else, his last action resonates with a magnitude that is as powerful as a political stand as it is as a last demonstration of a personal ethics which can be summarised as: moral integrity or nothing. A moral integrity, which he brought to bear indefatigably over the course of a lifetime in pursuit of freedom, resolution and independence – at whatever price.

The only thing worse than a good argument contrary to a conviction you hold is a bad argument in its favor. Overcoming a good argument can strengthen your position, while failing to may prompt you to reevaluate it. In either case, you’ve learned something—if perhaps at the expense of a cherished belief.

The only thing worse than a good argument contrary to a conviction you hold is a bad argument in its favor. Overcoming a good argument can strengthen your position, while failing to may prompt you to reevaluate it. In either case, you’ve learned something—if perhaps at the expense of a cherished belief.

As forced migration in the wake of war and climate change continues, and various administrations attempt to additionally restrict the movement of people while further “freeing” the flow of capital, national borders, nativism, and a sense of cultural rootedness have re-emerged as acceptable topics in a globalized order that had until recently believed itself post-national. In the German-speaking world, where refugees have been met with varying degrees of enthusiasm depending on their provenance, national pride, long taboo following the Second World War, at least in Germany, is enjoying a comeback. As the last generation of perpetrators and victims dies and a newly self-confident, unproblematically nationalist generation comes to consciousness, it is again becoming possible to use a romantic, symbolically charged term like Heimat.

As forced migration in the wake of war and climate change continues, and various administrations attempt to additionally restrict the movement of people while further “freeing” the flow of capital, national borders, nativism, and a sense of cultural rootedness have re-emerged as acceptable topics in a globalized order that had until recently believed itself post-national. In the German-speaking world, where refugees have been met with varying degrees of enthusiasm depending on their provenance, national pride, long taboo following the Second World War, at least in Germany, is enjoying a comeback. As the last generation of perpetrators and victims dies and a newly self-confident, unproblematically nationalist generation comes to consciousness, it is again becoming possible to use a romantic, symbolically charged term like Heimat. Sughra Raza. Don’t Step On The Jewels, 2014.

Sughra Raza. Don’t Step On The Jewels, 2014.